|

|

Artist Index  The Life, Letters and Work of

|

| 1. | Portrait of Lord Leighton (Photogravure) By G.F. Watts. |

To face Dedication |

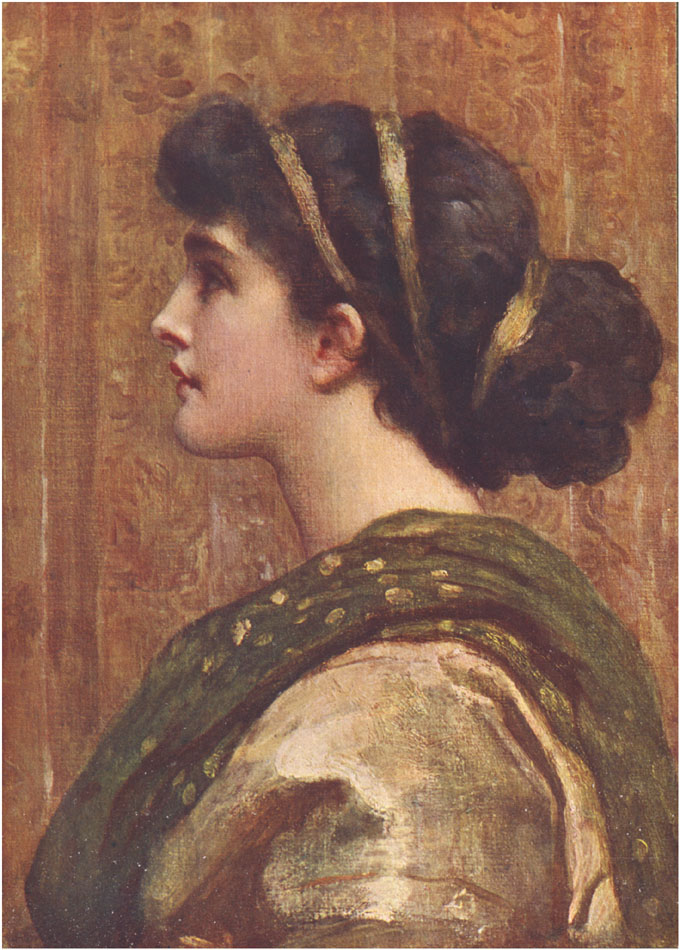

| 2. | Head of Young Girl (Colour) A wedding gift to H.R.H. The Prince of Wales, who graciously gave permission for the painting to be reproduced in this book. |

To face page 1 |

| 3. | "Eucharis," 1863 (Colour) By kind permission of Mrs. Stephenson Clarke. |

9 |

| 4. | "A Noble Lady of Venice," 1866 (Photogravure) By kind permission of Lord Armstrong. |

10 |

| 5. | "Greek Girls Picking up Shells by the Seashore," 1871 (Photogravure) By kind permission of the Rt. Hon. Joseph Chamberlain. |

18 |

| 6. | Portrait of Mrs. Sutherland Orr, 1861 | 57 |

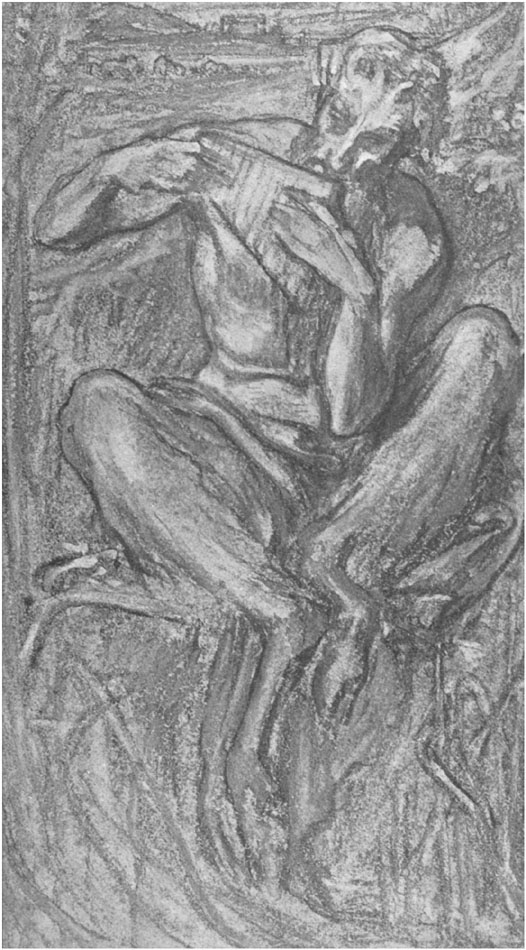

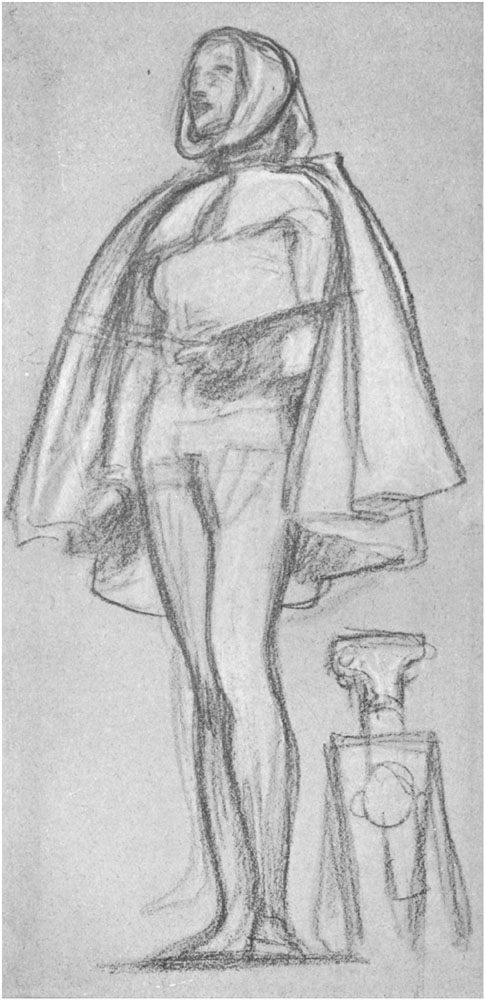

| 7. | Pencil Sketch for "Michael Angelo Nursing his Dying Servant," 1862 Leighton House Collection. |

93 |

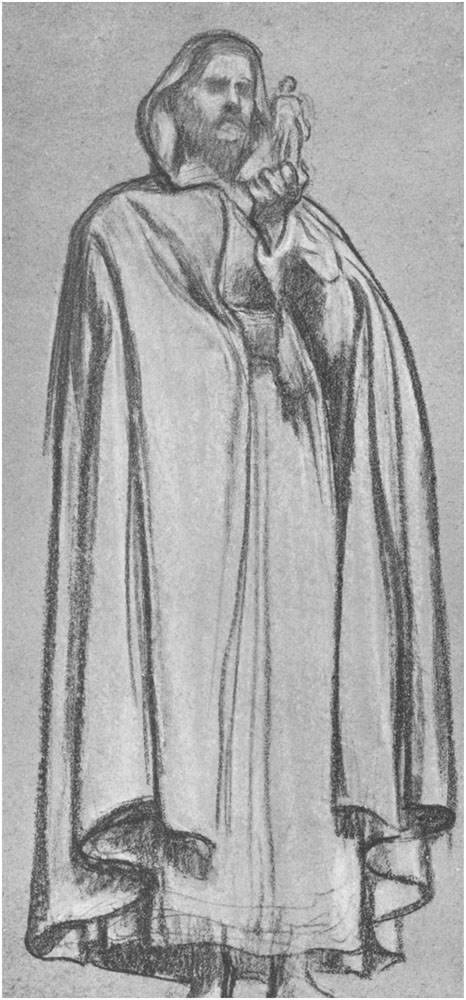

| 8. | Original Sketch for "Samson Wrestling with the Lion" Designed as an illustration for Dalziel's Bible. Leighton House Collection. |

94 |

| 9. | Original Drawing for the Great God Pan, Illustrating Mrs. Browning's Poem, "Musical Instrument" In "Cornhill Magazine," July 1861. Leighton House Collection. |

102 |

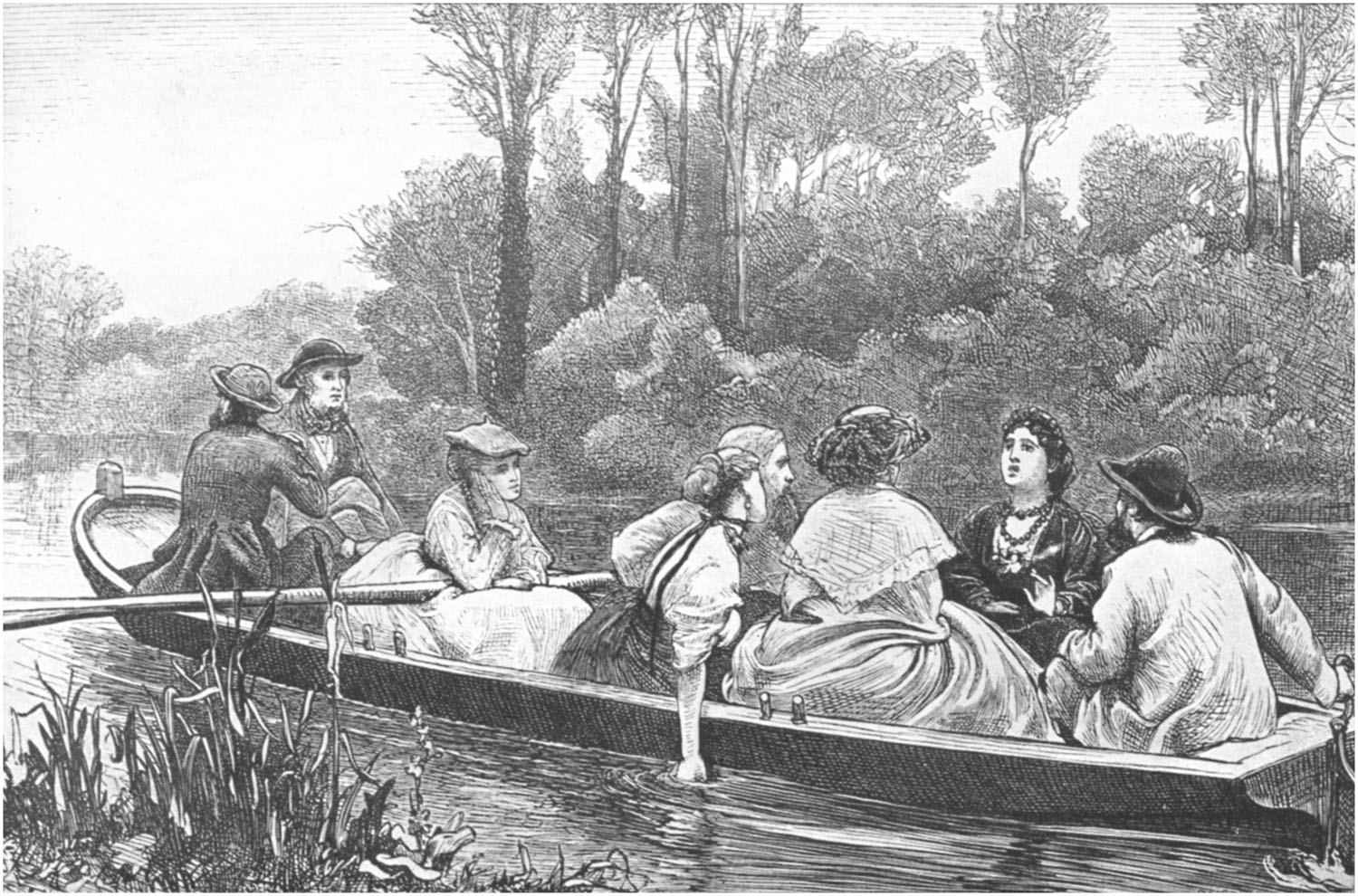

| 10. | "An Evening in a French Country House," Illustrating Mrs. Adelaide Sartoris' Story, "A Week in a French Country House," Published in the Cornhill Magazine, 1867 By kind permission of Messrs. Smith, Elder, & Co. |

103 |

| 11. | "Drifting." Second Illustration for same | 104[viii] |

| 12. | Lord Leighton Photograph taken at Lyndhurst, 1863. |

107 |

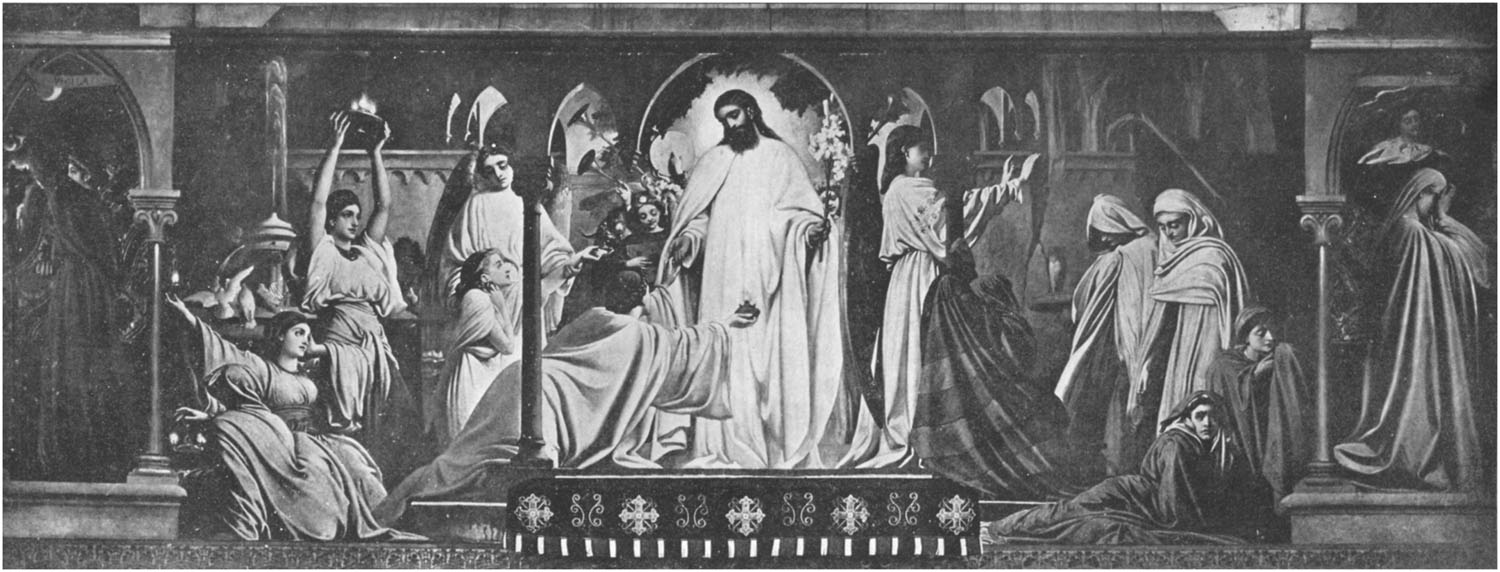

| 13. | Fresco for Lyndhurst Church—"The Wise and Foolish Virgins," 1864 | 111 |

| 14. | "Greek Girl Dancing," 1867 By kind permission of Mr. Phillipson. |

125 |

| 15. | Sketch for a "Pastoral," 1866 Leighton House Collection. |

125 |

| 16. | Sketch in Oils—"Egypt" (Colour) | 131 |

| 17. | "S. Jerome." Diploma Work, 1869 Gallery in Burlington House. |

188 |

| 18. | "Electra at the Tomb of Agamemnon" | 189 |

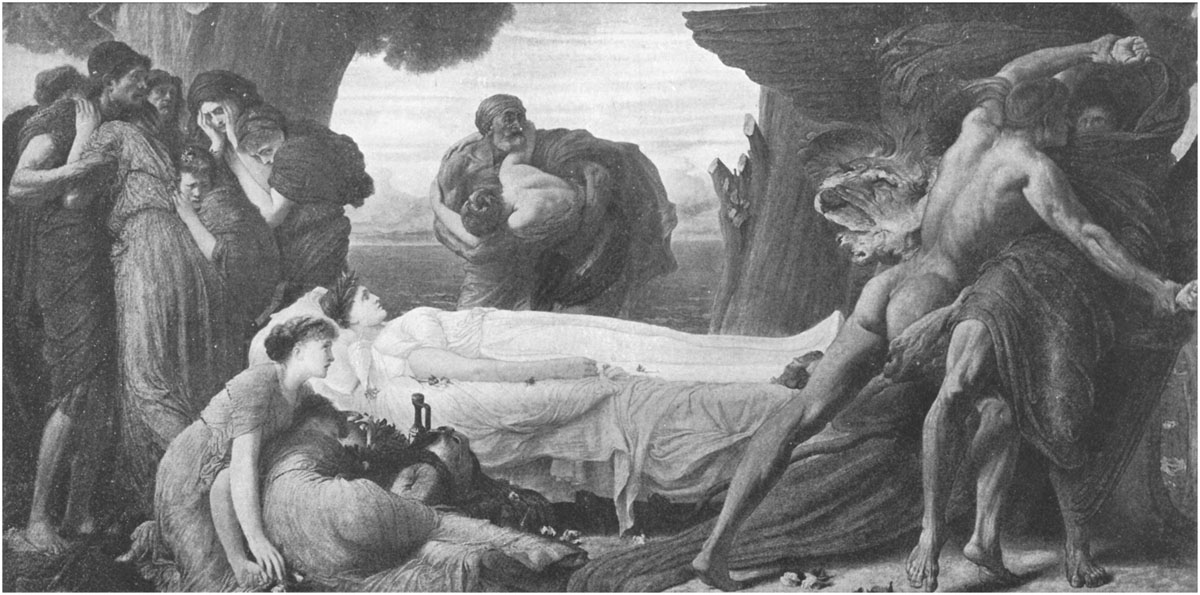

| 19. | "Heracles Wrestling With Death for the Body of Alcestis," 1871 By kind permission of the Fine Art Society. |

190 |

| 20. | "Summer Moon," 1872 By kind permission of Messrs. P. & D. Colnaghi. |

193 |

| 21. | "A Condottiere," 1872 The Walker Fine Art Gallery, Birmingham. |

193 |

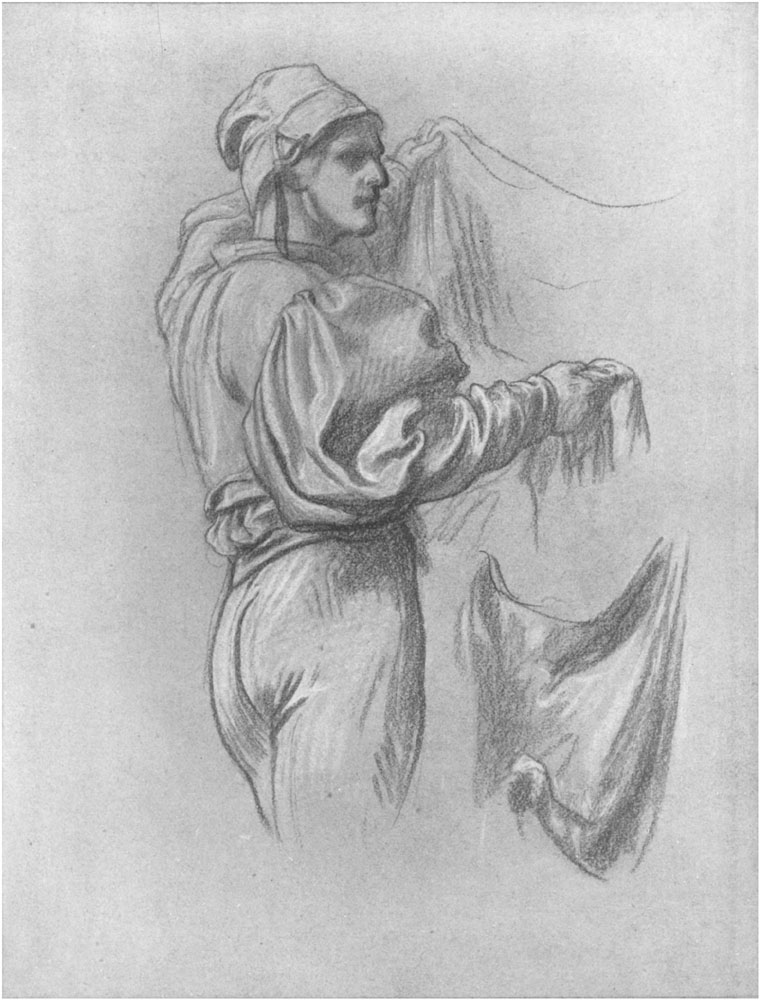

| 22. | Study for Figure in Frieze, "Music," 1886 Leighton House Collection. |

193 |

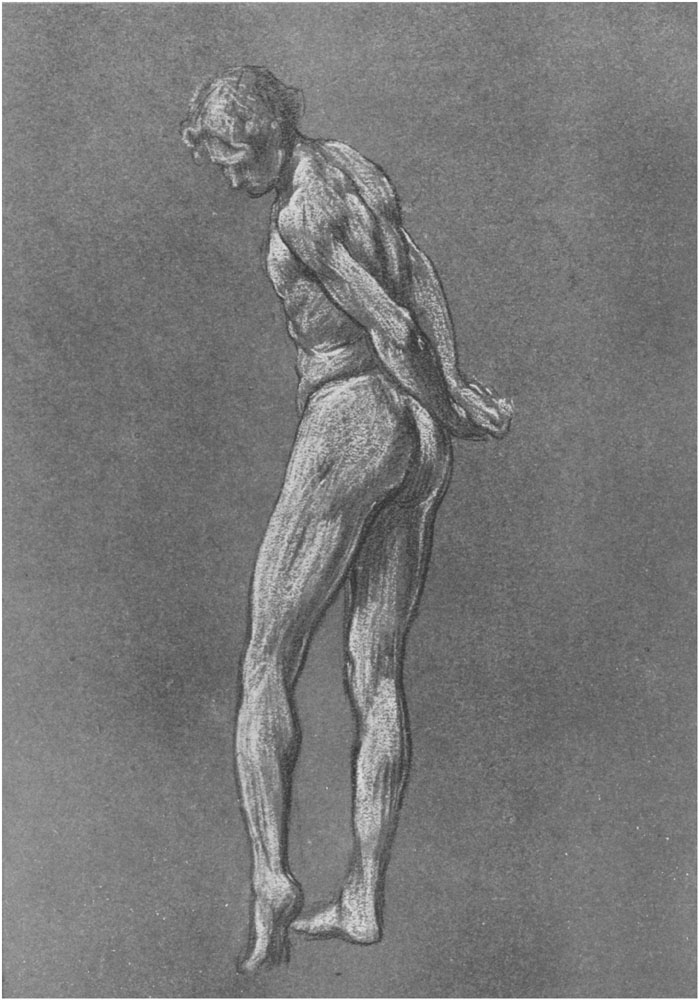

| 23. | Study of Man's Figure for the "Arts of War," 1872 Leighton House Collection. |

193 |

| 24. | Study of Man's Figure for the "Arts of War" Leighton House Collection. |

193 |

| 25. | Study of Man's Figure for the "Arts of War," 1872 Leighton House Collection. |

193 |

| 26. | "Antique Juggling Girl," 1874 (Photogravure) By kind permission of Mr. Hodges. |

194 |

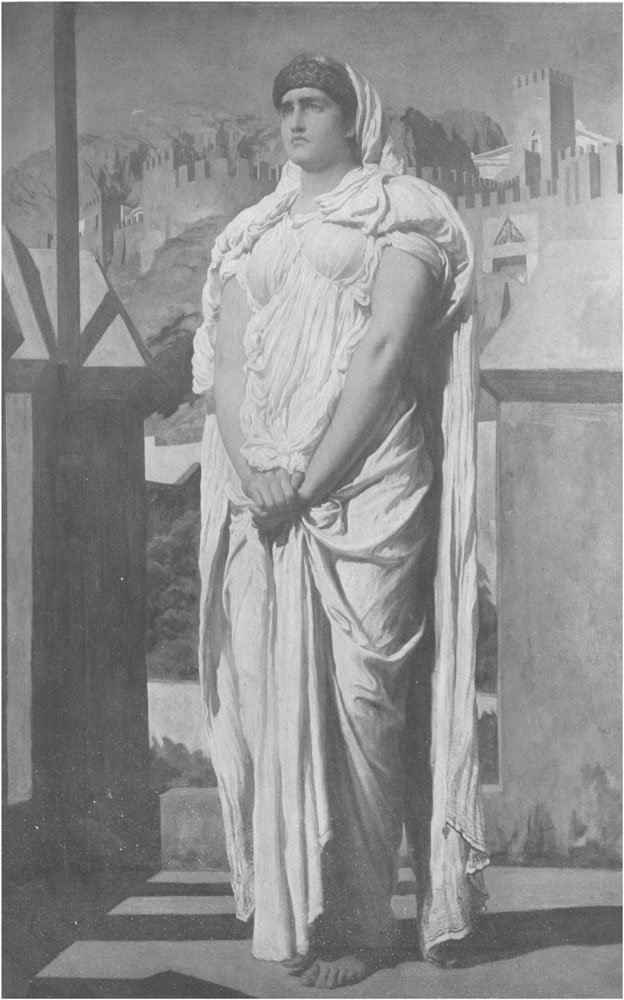

| 27. | "Clytemnestra from the Battlement of Argos Watches for the Beacon Fires which are to announce the Return of Agamemnon," 1874 (Photogravure) Leighton House Collection. |

194[ix] |

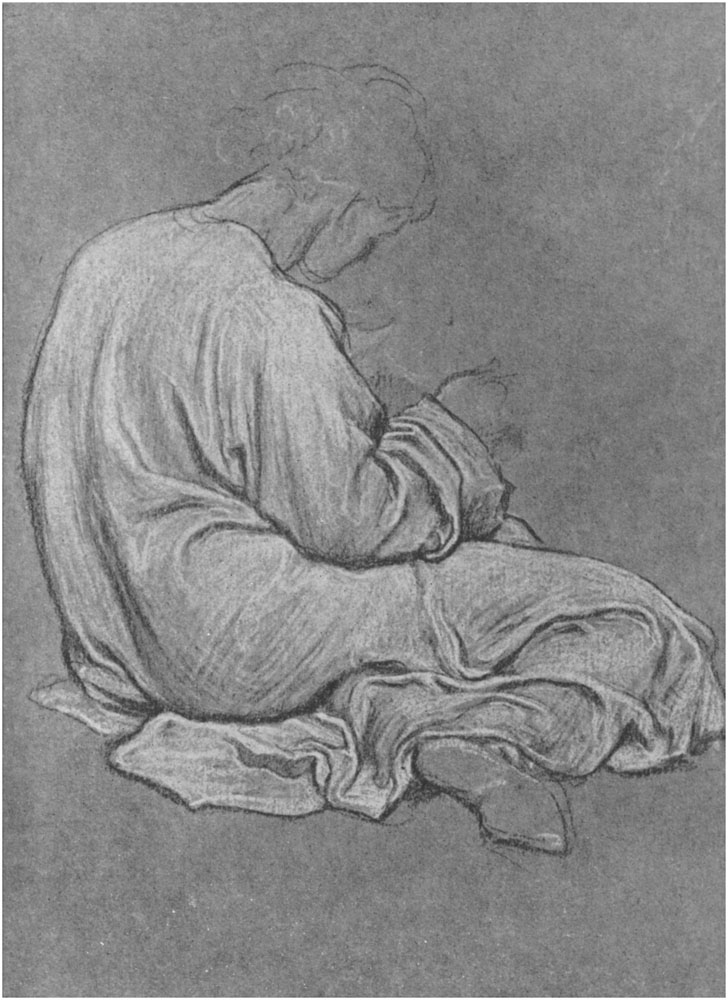

| 28. | Study for "Clytemnestra" Leighton House Collection. |

194 |

| 29. | Study for "Summer Moon" (Colour) Executed by moonlight in Rome. Given by the late A. Waterhouse, R.A., to the Leighton House Collection. |

194 |

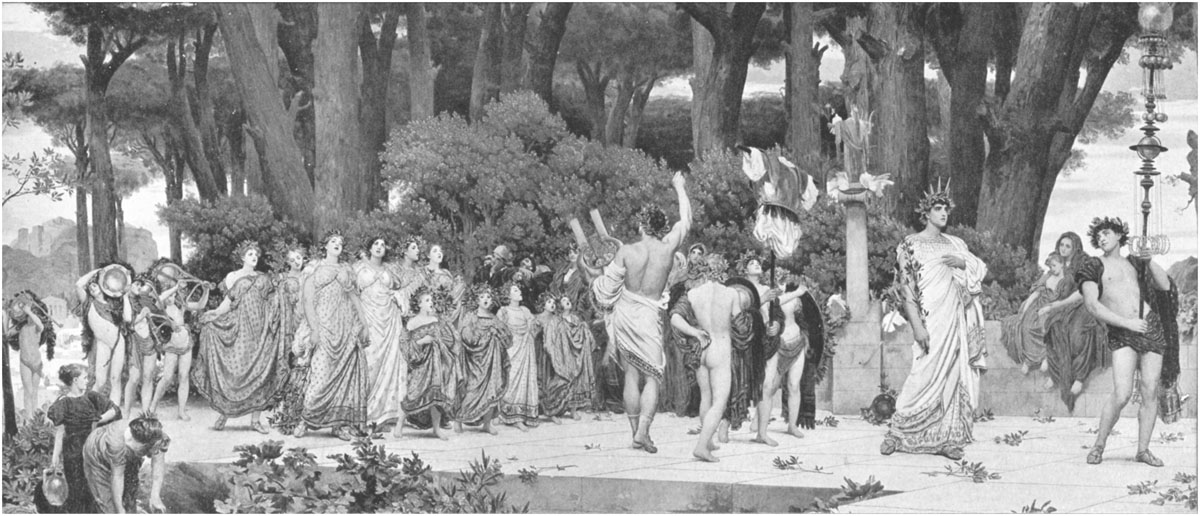

| 30. | "The Daphnephoria," 1876 By kind permission of the Fine Art Society. |

197 |

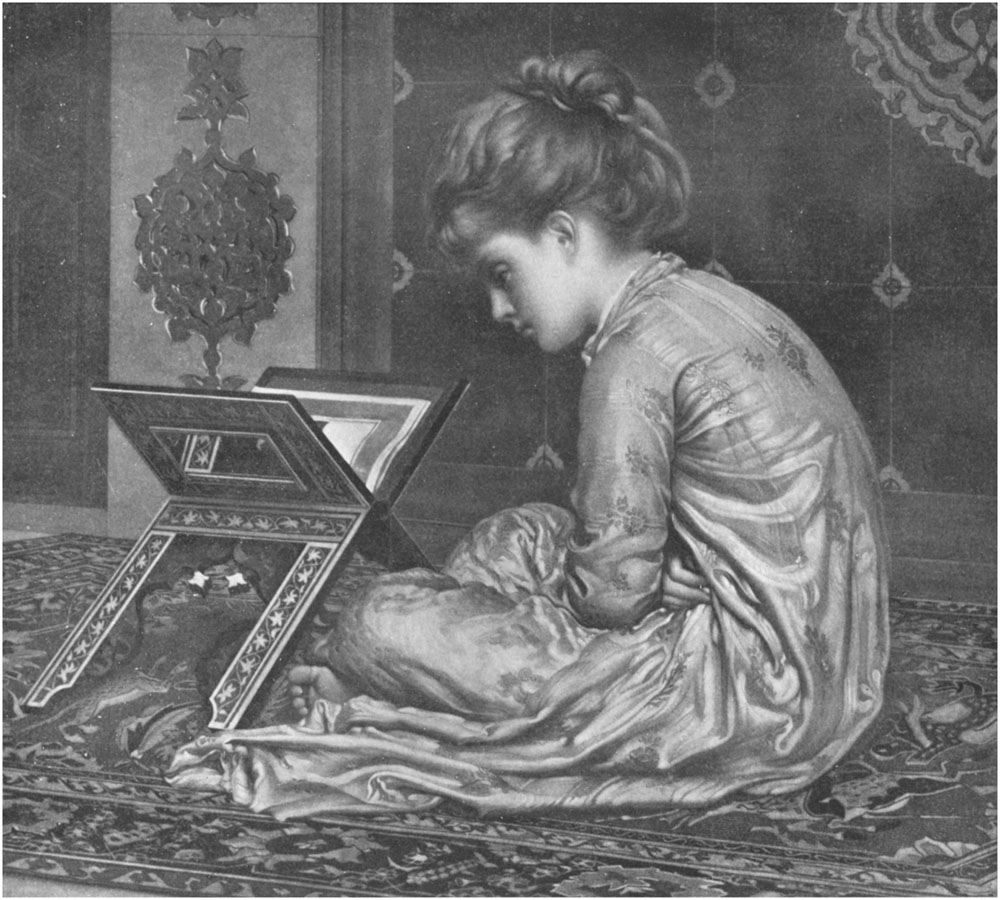

| 31. | "At a Reading-desk," 1877 By kind permission of Messrs. L.H. Lefevre & Son. |

197 |

| 32. | Original Study for "An Athlete Struggling with a Python," 1876 Given by the late G.F. Watts to the Leighton House Collection. |

199 |

| 33. | "Nausicaa," 1878 | 201 |

| 34. | Study for Group in the "Arts of Peace," 1873 Leighton House Collection. |

202 |

| 35. | Study for the Figure of Cimabue, carried out in Mosaic in the South Court of the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1868 Leighton House Collection. |

203 |

| 36. | Study for the Figure of Niccola Pisano, carried out in Mosaic in the South Court of the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1868 Leighton House Collection. |

203 |

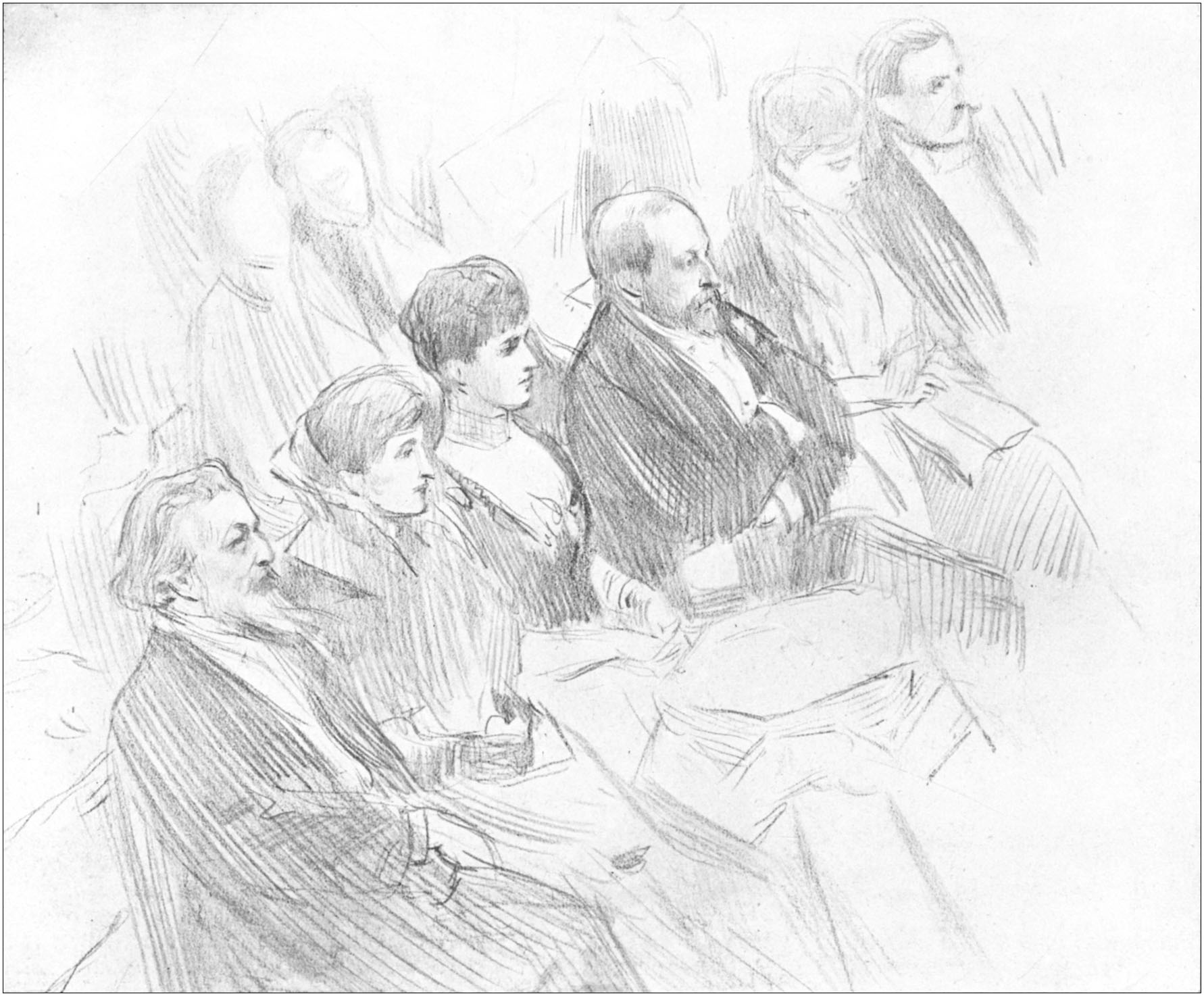

| 37. | Sketch of the Prince and Princess of Wales, attended by Lord Leighton, when present at a Monday Popular Concert in St. James's Hall Drawn at the time by Mr. Theodore Blake Wirgman. |

216 |

| 38. | Portrait of Sir Richard Francis Burton, K.C.M.G., 1876 | 218 |

| 39. | View of Arab Hall, 1906 Leighton House Collection. |

221[x] |

| 40. | Portrait of Professor Giovanni Costa Executed at Lerici in 1878. |

222 |

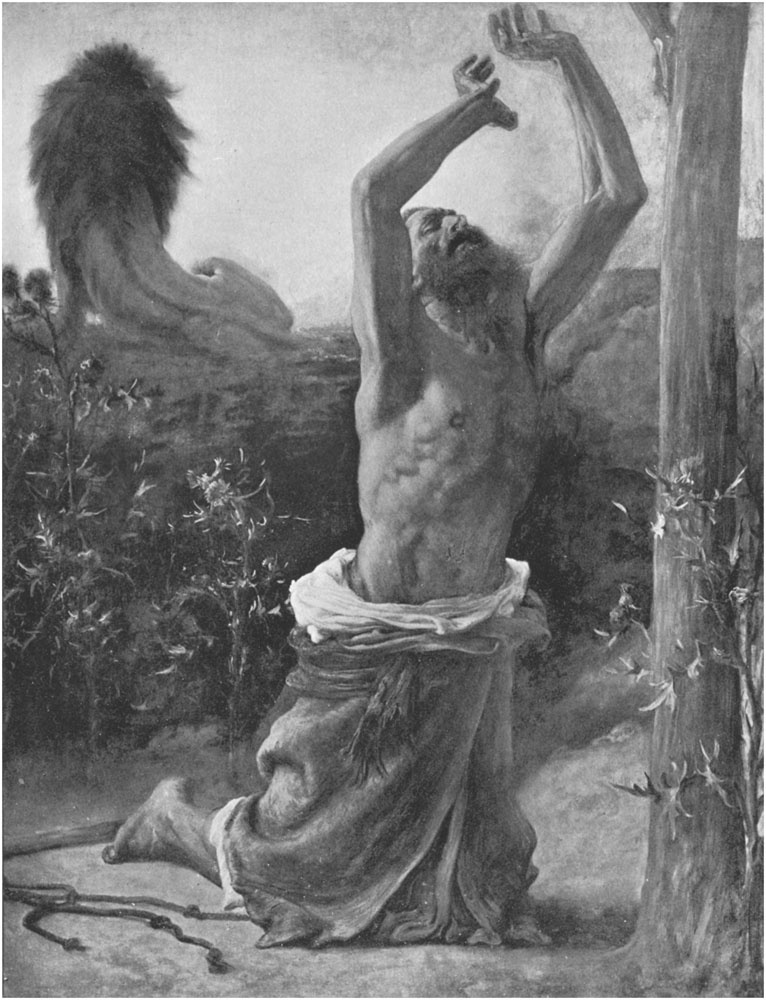

| 41. | "Elijah in the Wilderness," 1879 | 255 |

| 42. | Study for the Figure of "Elijah" Leighton House Collection. |

255 |

| 43. | "Neruccia," 1879 (Photogravure) By kind permission of Mrs. C.E. Lees. |

255 |

| 44. | "The Bath of Psyche," 1890 (Photogravure) The Tate Gallery. |

255 |

| 45. | "The Light of the Harem," 1880 By kind permission of the Leicester Gallery. |

256 |

| 46. | Drawing of Complete Design for "And the Sea Gave up the Dead that were in it," 1892 | 256 |

| 47. | Study for "Music." A Frieze, 1886 Leighton House Collection. |

256 |

| 48. | Study for "Andromeda," 1890 Leighton House Collection. |

256 |

| 49. | Study from Clay Model for "Perseus," 1891 Leighton House Collection. |

256 |

| 50. | Study for "Phoenicians Bartering With Britons" Leighton House Collection. |

256 |

| 51. | "Cymon and Iphigenia," 1884 (Photogravure) The Corporation of Leeds. |

256 |

| 52. | Sketch in Oils for "Cymon and Iphigenia" (Colour) By kind permission of Mrs. Stewart Hodgson. |

256 |

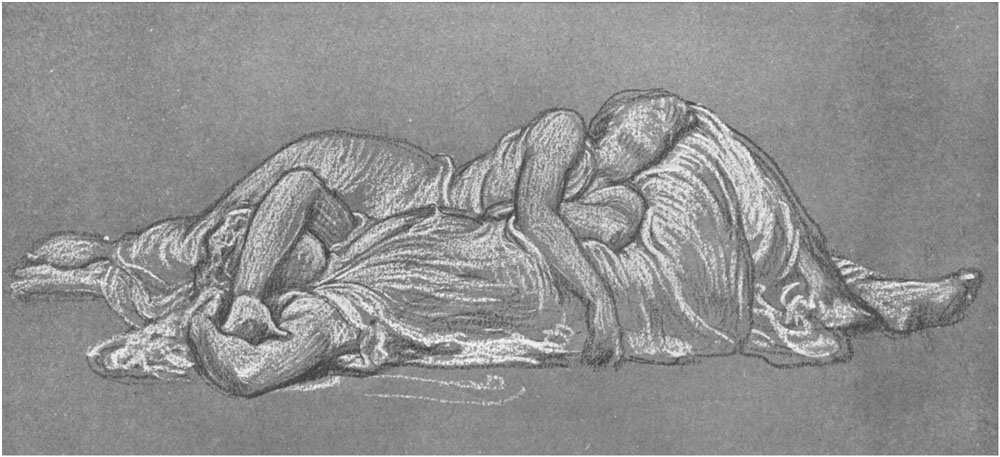

| 53. | Study for Sleeping Group in "Cymon and Iphigenia" Presented to the Leighton House Collection by G.F. Watts. |

256 |

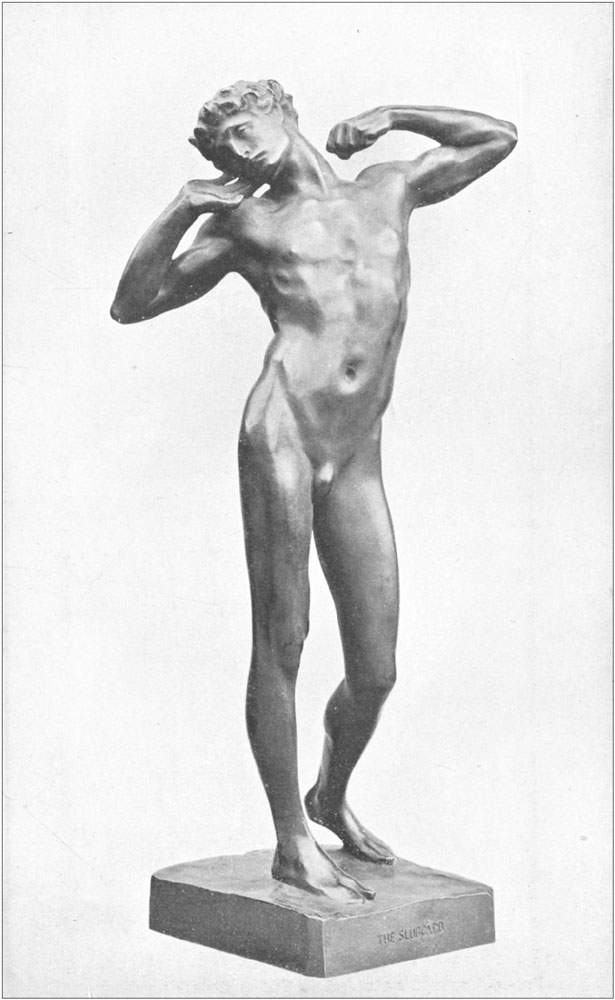

| 54. | From Bronze From Small Model in Clay by Lord Leighton of "A Sluggard," 1886 Leighton House Collection. |

258[xi] |

| 55. | "Needless Alarms," From Bronze Statuette, 1886 Leighton House Collection. |

258 |

| 56. | "The Last Watch of Hero," 1887 Corporation of Manchester. |

259 |

| 57. | Sketch in Oils for "Tragic Poetess," 1890 (Colour) By kind permission of Mrs. Stewart Hodgson. |

259 |

| 58. | "Atalanta," 1893 By kind permission of the Berlin Photographic Co. |

261 |

| 59. | "Flaming June," 1895 By kind permission of Mrs. Watney. |

261 |

| 60. | Study for "Flaming June" Leighton House Collection. |

261 |

| 61. | "Fatidica," 1894 By kind permission of Messrs. T. Agnew & Sons. |

261 |

| 62. | Studies for "Fatidica" Leighton House Collection. |

261 |

| 63. | "Memories," 1883 By kind permission of Messrs. P. & D. Colnaghi. |

266 |

| 64. | "The Jealousy of Simœtha the Sorceress," 1887 | 266 |

| 65. | "Letty," 1884 (Colour) By kind permission of Mrs. Henry Joachim. |

266 |

| 66. | Studies From Dorothy Dene for "Clytie," 1895 Leighton House Collection. |

268 |

| 67. | Sketch in Oils for "Greek Girls Playing at Ball," 1889 (In Colour) By kind permission of Mrs. Stewart Hodgson. |

274 |

| 68. | "Bacchante," 1892 (Photogravure) By kind permission of Messrs. Henry Graves & Co. |

287 |

| 69. | Sketch in Oils for "Bacchante" (Colour) By kind permission of Mrs. Stewart Hodgson. |

287[xii] |

| 70. | "Der Winter" Drawing by Eduard von Steinle. |

304 |

| 71. | Sketch in Oils for "Solitude" (Colour) By kind permission of Mrs. Stewart Hodgson. |

310 |

| 72. | "Summer Slumber," 1894 (Photogravure) By kind permission of Mr. Phillipson. |

316 |

| 73. | Sketch for "Summer Slumber" Presented to the Leighton House Collection by H.M. The King. |

316 |

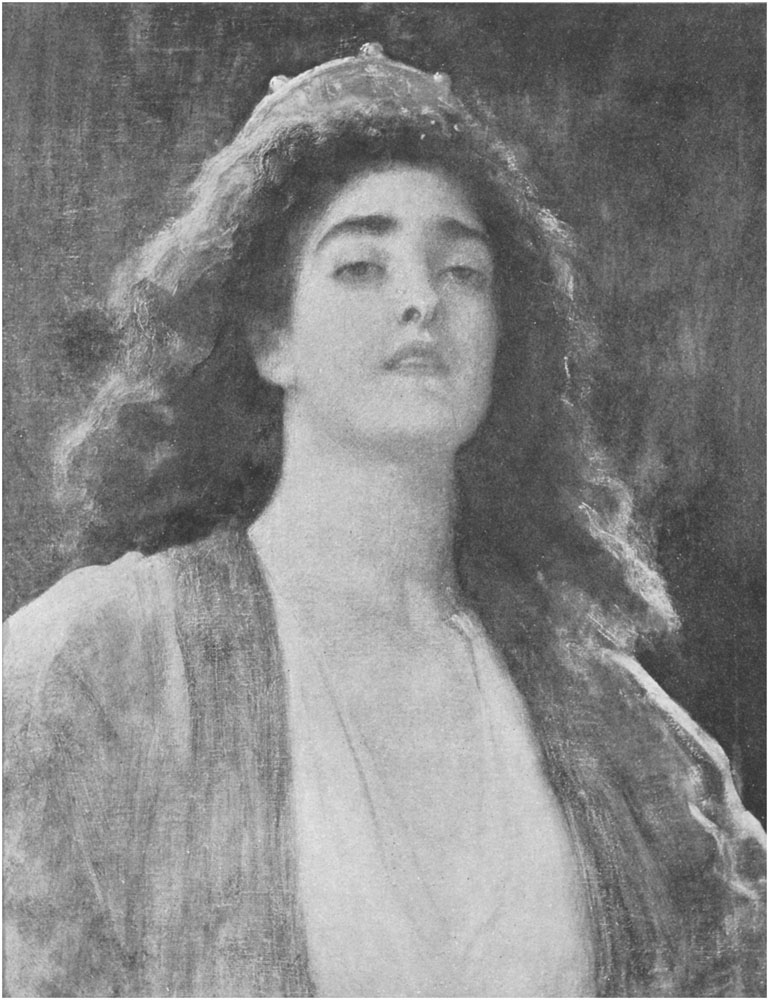

| 74. | "The Fair Persian," 1896 By kind permission of Sir Elliott Lees. |

324 |

| 75. | "The Spirit of the Summit," 1894 | 334 |

| 76. | Study for "Lachrymæ," 1895 Leighton House Collection. |

335 |

| 77. | "Clytie," 1896 By kind permission of the Fine Art Society. |

336 |

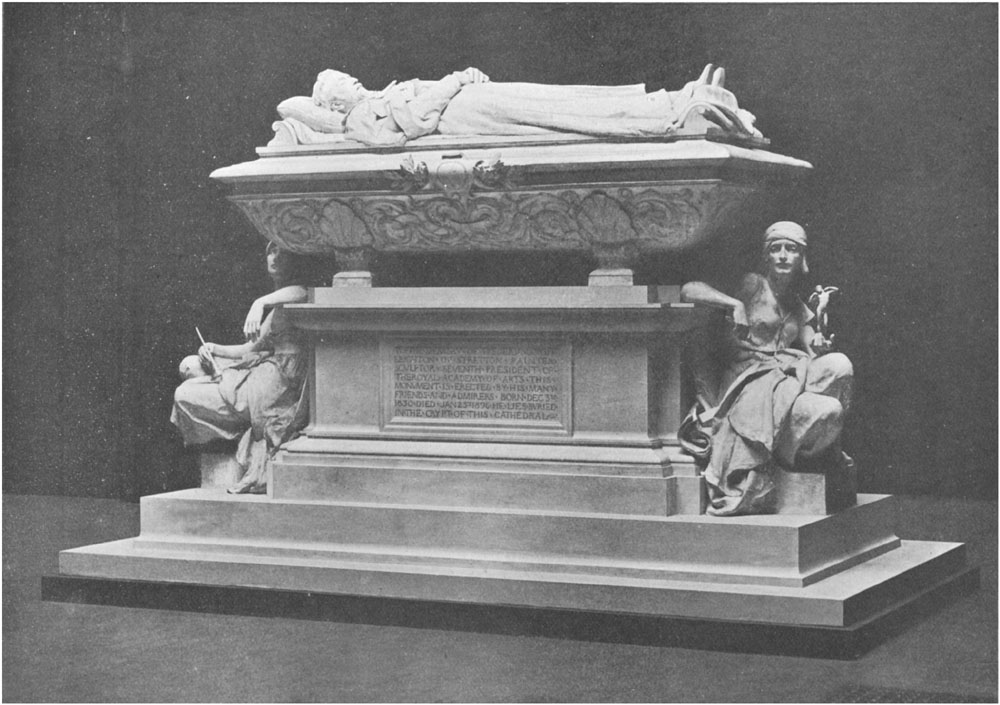

| 78. | Memorial Monument in St. Paul's Cathedral to Frederic Baron Leighton of Stretton | 340 |

| 79. | View of Hall and Staircase of Leighton House, given by Lord Leighton's Sisters to the Public as a Memorial to their Brother By kind permission of Mr. J. Harris Stone. |

340 |

HEAD OF YOUNG GIRL

Wedding present from Lord Leighton to H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, who has graciously allowed the painting to be reproduced in this bookToList

Sir William Richmond, R.A., and Mr. Walter Crane have kindly contributed the following notes:—

It was in 1860 that I first knew Leighton. We met over affairs connected with the Artist Rifle Corps at Burlington House, and afterwards at the studios of various artists, where discussions took place regarding the formation and means of conduct of the Corps. On several occasions I walked home with Leighton to his house in Orme Square.

I don't think I have ever known a man who grew more steadily than Leighton did. The effort of his artistic life was to remove the effects of a certain mannerism and over-education in his early artistic life. His knowledge was wonderful, his powers of design without immediate consultation with Nature were phenomenal; he feared the facility in himself and went always to Nature, that out of her manifold gifts he should be inspired directly by them. And this constant study had its drawbacks as well as its merits, because in one sense it stood in the way of the development of an abstract power of invention. If ever an artist made the most of his conscious abilities, Leighton did. His character was so curiously simple on the one hand, and so complicated on the other, that a balance between a very emotional and extremely accurate temperament had to be found, and it was found. How far a certain charm of spontaneity was obscured a little, perhaps by erudition and a sort of Aristotelian preciseness, it is not for me to say. There is in all things a balance which, when once obtained, reduces the weight in [2]both scales. But we must take a life as it has been made by circumstances, by early training and after influences; and probably most men who are in earnest,—and Leighton was pre-eminently in earnest,—find their proper issue finally. That the best of Leighton's work will live, I am convinced; that it will hold its own when a great deal of other work praised, admired, even worshipped during the life of his contemporaries shall be dead, I feel quite assured; and one may very justly be asked—Why? The simple answer is that it was thorough, definite, sincere, accomplished. Leighton never put out his hand towards the limbo of vulgarity or fashion. Like Virgil, like Mendelssohn, Leighton was a stylist, and his life's work showed a perfection of attainment upon the lines which he drew out for his progress almost to my thinking unrivalled in the work of any of his contemporaries. Here and there he struck a deep note of poetry, here and there he was like a Greek for his simplicity, here and there his work shows the luxury of the Venetians, the restraint of the Florentines, but never perhaps the majesty of M. Angelo or the strong charm of Raphael. His art was eclectic; still it was Leighton, and could have been done only as the result of great natural gifts, assiduous study, force of character, and, withal, independence of vision. His love of beauty was his own personal love, not learnt, hardly perhaps inherited, but spontaneous and lasting. This devotion to beauty may have sometimes led his emotions away from character, which sometimes is very nearly ugly as well as very nearly allied to the highest beauty, which Bacon says has always something of strangeness in it. The pursuit of beauty, per se, may be purchased at the expense of character.

But Leighton was always pulling himself up; and when he found himself too facile, too ornate, he resolutely set his mind to correct any tendency in that direction by fidelity to Nature, sometimes even to her ugly movements. Excess was not in his nature, which was curiously logical; his mind was swift, far-seeing; in debate he was admirable, always seeing the weak point of an argument at once, and "partie pris" was his abomination. A man so gifted in the essence and laws of form, so learned in the construction of the human frame, so deeply sensitive to line and movement as well as to structure, surely would have given to the world great works of sculpture. Indeed he did, but not enough! One regrets that—still [3]one must accept the fact that form is but little cared for in this country, and Leighton sinned by reason of his love of form; by many he was called not a painter because he did not smear, did not trust to accidents, did not leave works half done—because he was sincere to his conviction that a work of art must be, to last, complete "ad unguem." The present craze for incompleteness, for sketches instead of pictures, for unripe instead of ripe fruit, must die as all false notions die; the best, the rightest will live; and when the present ephemeral fashion has worked itself out, the nobility of Leighton's works, his best, are certain to take their place in the estimation of those that know as surely as that they are good.

How many out of the multitude really, if we could test them, care one jot for the Elgin Marbles, for the Demeter of Knidos, for the vault of the Sistine Chapel?—very few. Really great things never can be accepted by the commonplace. How should they be? for to understand the highest in music, in architecture, sculpture, or painting, the observer or listener must have a spark in his constitution which is a portion of the flame that burned white heat in the soul of the conceiver. How can such an attitude of intimate sympathy belong to the many? It never has, and probably never will. Great men are rare, and those who are mentally or organically made to comprehend them are rare also. The great can afford to wait because they are immortal. In all one's dealings with Leighton what did one find? a noble nature, restrained, charitable, in earnest; and if in many discussions as to the desirability of certain events, certain compromises, certain acts of conformity, one did not agree with Leighton, one knew "au fond" that the attitude was quite logical, not hastily arrived at, and the position taken up was to be strenuously held: and it was that power of consistency which made Leighton so trustworthy. He was fearless when his principles were touched, he was loyal to his associates in the Academy even if he did not see eye to eye with them, and he was loyal to his art and to his friends. If Leighton had chosen politics for his career he would probably have been Prime Minister, just as Burne-Jones might have been Archbishop of Canterbury had he continued his early and very remarkable theological studies. All really great men have endless possibilities. It is more or less chance which decides the direction of ability, which, once discovered, forcibly, dominantly present, [4]must find opportunities for its highest development and achievement in the tenure of the goal. It was ability and natural gifts that made Leighton great, industry that nourished his greatness, and stability to principle which made it lasting in his lifetime, and must for all time stamp his work. The thing that really engages one's interest about a great man is not so much his "technique" as his general disposition and character, which forms for itself a suitable "technique" by which his achievements have been manifested. Should any one by-and-by describe the "technique" of Joachim, the supreme violinist, he would probably interest a few, but in reality he would say nothing really valuable, excepting inasmuch as he touched upon first principles. The "modus operandi" of an artist's life is moulded by his personal aims, the means are those by which he found his own way of stating them; and one doubts very much if, after all, the points which differentiate one man's work from another's are not those which have obliterated the conscious efforts, preserving just the touches which genius gives beyond and above all laws that may be learnt. Verse no doubt is much dependent for its beauty on the system of the arrangement of syllables, and the music they make when harmoniously handled upon the final perfection which they reach, and so become rule-making instead of being the result of rule-following. Hence lies that unaccountable beauty which is the inexplicable result of the ego—that taste, that selection, that special word which creates an impression immediately, and which seems inimitable even, and obviously the only one which could have been used; that is style—the very essence of the ego which cannot be copied, or indeed again brought into relation with the idea. And isn't that the reason why the copy of a picture can never be really like an original? even if the "technique" is identical, it lacks that last touch, that last word which transcends tradition, almost transcends thought, for it is just the thought which has been summed up in a moment of inspiration, uncalculated, spontaneous. Leighton was far too wise a man to believe in the constant recurrence of inspirations: he knew that the moment when the whole spirit is ready to act is involuntary; he knew that to reach the supremacy of that moment, labour was necessary; that in labour is the foundation of the building for that moment of inspiration. One may question if the first vision in Leighton was very [5]strong—strong as Blake's, strong as many artists whose powers of attainment were much less than Leighton's, but whose vision was clearer at the outset. Rougher minds than Leighton's have produced more epic effects, and a ruder, less accomplished "technique" has borne with it more original, more trenchant ideas. Leighton was not a mystic; he dealt with thoughts which he embodied in forms that he saw, but which he also made his own in their application; that was his genius of originality. The rugged verse of Æschylus had no place in his temperament, much as he admired it; the polished diction of Virgil bore more similitude to Leighton's inspiration. Sometimes one missed in his work just the touch of the rugged which would have given more grace by comparison, by contrast. His grace of diction, his oratory, his writing, was sometimes over-refined, and missed its mark by over-elaboration. The very speciality of Leighton was completeness. One has seen pictures in his study only half finished, which had a charm of freshness that vanished as each portion became worked into equal value. But that fastidiousness was his characteristic, it was part of him; and therefore we must not deplore it. His originality was exemplified by his power of taking pains, his power of will to do his very best according to his guiding spirit of thoroughness. Temperaments are so different. Whistler could not be Leighton. Because we admire the one, it is not necessary to decry the other; that is weak criticism, or rather none at all. The spirit which inspires the impressionist is not the spirit of design, but a limited observation in a very restricted area. We can have the Academic as well as the Impressionist: both are useful as foils to each other, and it is just as narrow of the Impressionists to want all men to see nature and art as they see them, as it has been for the Academics to see "nothing" in the newer if more limited system. I believe that Leighton's real love was early Italian art; all that came to him after was the result of growth. His enthusiasm for Mino da Fiesole, for the earlier Raphaels, for Duccio of Siena, for Lorenzetti, was evident and absorbing; other enthusiasms were more branches from the stem than its roots. He loved line; he found it there: he loved restraint of action, pure sensuous beauty; he found it in early Italian Art. The reserve of emotions touched him in Greek Art—its suavity, its almost geometrical precision, the tunefulness and melody of its rhythmical [6]concords. His love of music was on the same lines: Wagner never appealed to him as Mozart did; it was too strenuous, too busy in changes of key, too incomplete in the finish and development of phrases. It was not that he liked dulness—not a bit; he was emotional, often gay, often depressed—excitable even; but to him Art was an intellectual more than a purely emotional system, and he liked it to be finished, consistent, perfect—and those qualities he strove for, without a doubt he obtained in a high measure. It will be long before we see again the like of Frederic Leighton, a man complete in himself.

W.B. Richmond.

June 1906.

I first met Leighton about 1869 or '70, I think. I went to one of his receptions at the Studio in Holland Park Road, at the time he was showing his pictures for the Academy. I think his principal work of that year was "Alcestis," or "Heracles Wrestling with Death." About the same time Browning's poem of "Balaustion's Adventure" appeared, in which he alludes to Leighton and this very picture in the lines beginning:

(if I remember rightly).

I availed myself of a friend's introduction, and presented myself. One recalls the courteous and princely way in which he received his guests on these occasions, and the crushes he had at his studio—Holland Park Road blocked with carriages, and all the great ones of the London world flocking to see the artist's work.

About this time, or shortly before, he had done me the honour to purchase two landscape studies I had made in Wales from among a number in a book, which was shown him by my early friend George Howard (now Earl of Carlisle), and I remember his kind words in sending me what he deemed "the very modest price" I had asked for them.

[7]His kindness to students and young artists was well known. He would take trouble to go and see their work, and he was always an admirable and helpful critic.

I remember, on my first visit to Rome in the autumn of 1871 (on our marriage tour), going into Piali's Library one evening to look at the English papers. No one was there, but presently Leighton came in. He did not remember me at first, but I recalled myself to him. He was very kind, in his princely way, and gave me introductions to W.W. Storey, the sculptor, and his great friend, Giov. Costa, and he called at our rooms to see my work, in which he showed much interest. In a letter I had, dated March 1st, 1872, written from the Athenæum Club, he speaks of some drawings I had sent to the Dudley Gallery, one he had seen on my easel in Rome, and he says: "I have seen your drawings, all three—one was an old friend; of the other two, the 'Grotto of Egeria,' with its 'sacrum numes,' most attracted me through its refined and sober harmony. The quality of your light is always particularly agreeable to me, and not less than usual in these drawings"; he goes on to say he is glad to hear I have "made friends with my excellent Costa, who as an artist is one in hundreds, and as a man one in thousands"; he adds, "Have you sketched in the 'Valley of Poussin'? It strikes me that old castle would take you by storm."

I saw Leighton again in Rome in 1873, meeting him on the Palatine, among the ruins of the Palace of the Cæsars. He was with a lady who, I believe, was the author of the story published in The Cornhill, "A Week in a French Country House," for which Leighton made an illustration. (His black and white work was always very fine, and I recall seeing some of his drawings on the wood for Dalziel's Bible and "Romola.")

Later, he came to see us when we settled in London, in Wood Lane.

I had further relations with him about the time he was building the Arab Hall, when (through George Aitcheson, his architect) I designed the mosaic frieze. On some sketches I made for this he writes: "Cleave to the Sphinx and Eagle, they are delightful—I don't like the duck-women." With regard to these Arab Hall mosaics, he said that he hoped to have more, [8]and eventually "to let us loose (Burne-Jones and myself) on the dome."

After this, I saw something of Leighton on the committee of the South London Fine Art Gallery, Peckham, in its earlier days, when he was chairman, and helped to pilot the institution from the somewhat exacting proprietorship of its founder towards its ultimate position as a public institution.

From the aristocratic point of view, he certainly had a keen sense of public duty, and probably laid the motto "Noblesse oblige" to heart.

I met him again at the Art Conference at Liverpool, when a trainful of artists of all ranks went down together, and some notable attacks were made on the Royal Academy. Leighton was tremendously loyal to that institution, which I notice is always stoutly defended by its members, whatever opinions they may have expressed while outsiders.

I suppose we differed profoundly on most questions, but he was always most courteous, and, whatever our public opinions, we always maintained friendly personal relations; and I may say I always entertained the highest admiration for Leighton's qualities, both as an artist and as a man.

At the time when the election for the presidency of the Academy was in view (after the death of Sir Francis Grant), it was said that Leighton was the only man, and that if they did not elect him the institution would go to pieces; but probably as president he had less power of initiative than before.

I remember, after one of our committees at his studio, he drove me home to Holland Street in his victoria; and as he set me down at my door, he pointed to a little copper lantern I had put up over the steps, and said, "Is that Arts and Crafts?"

His fondness for Italy was well known, and I think he went every autumn. I recall meeting him at Florence in 1890, while staying at the delightful villa of Mrs. Ross (Poggio Gherardo), when he came to luncheon.

In death he was as princely as in life; and on the day of his burial at St. Paul's I was moved to write the following as a tribute to his memory, which will always be vivid in the hearts of those who had the privilege of his friendship:—

[9]Having settled in England in 1860, Leighton found that there, contrary to his expectations, his sense of colour became developed; and with this his individuality as a painter asserted itself. Between the years 1863 and 1866 he painted pictures which proved that, as a distinct artificer in painting, he had found himself, and was no longer under the controlling influences of German or Italian Art, though, unfortunately, hints of German methods in the actual manipulation of his brush clung more or less to his painting to the end. From boyhood Leighton's power of designing, his sense of beauty in line and form and of dramatic feeling, his extraordinary facility in drawing with the point, proved his genius as an artist; but it was not till the early sixties that his pictures proved him to be possessed of individual distinction as a painter, probably because the method of handling the brush associated with the teaching which, in other respects, commanded his reverence and admiration, were alien to his finest artistic sense. No later works are to be found more notable in luminous quality of painting than "Eucharis," 1863, and "Golden Hours," 1864; none in strength and [10]solidity of texture, or in beauty of distinguished handling, than "A Noble Lady of Venice," about 1865; none in richness of arrangement combined with the fair aerial atmosphere appropriate to a Grecian scene, for which Leighton had so native a sympathy, than "A Syracusan Bride Leading Wild Beasts in Procession to the Altar of Diana," 1866.[1] [11]Later works may claim a greater public prominence among his achievements, but for actual individuality and feeling for the beauty which appealed most strongly to Leighton in colour as in form, none he painted after evinced any fresh departure.

As early as 1852, at the age of twenty-one, Leighton wrote to Steinle from Venice: "I must candidly confess that great as my admiration for Titian (& Co.) was, yet the well-known art treasures here have seized me and entranced me anew. You, dear master, are so familiar with all these things that there is nothing I can write you about them; but on one point I am fairly clear, namely, that the admirers and imitators of Titian (particularly the latest) seek his charms quite in the wrong place, and I am convinced that the impressiveness of his painting lies far less in the ardour of his colouring than in the stupendous accuracy and execution of the modelling." In another letter to Steinle he refers to the necessity of mastering the capacities of the brush in order to render form in a complete manner independently of the function of the brush to render colour.

"Those who place the brush behind the pencil, under the pretence that form is before all things, make a very great mistake. Form is certainly all important; one cannot study it enough; but the greater part of form falls within the province of the tabooed brush. The everlasting hobby of contour (which belongs to the drawing material) is first the place where the form comes in; what, however, reveals true knowledge of form, is a powerful, organic, refined finish of modelling, full of feeling and knowledge—and that is the affair of the brush (Pinsel)."

In January 1860 Leighton wrote to Steinle: "You will perhaps be surprised, but, in spite of my fanatic preference for colour I promised myself to be a draughtsman before I became a colourist," and in fact Leighton was fighting, [12]throughout his whole career, against allowing the sensuous qualities in his art to override those which the teaching of Steinle had proved to his nature to be the most truly elevating and ennobling. Up to the age of thirty he had been overshadowed by the influence of others in the matter of actual technique in painting. From the time he settled in London he freed himself from the tutelage of all masters. As we have read in his letters, his intention was to do so in 1856 when he painted "The Triumph of Music;" but at that time he failed in finding his real self in his painting of that picture, and fully realised that he must reculer pour mieux sauter, returning in the autumn of that year to Rome to be fed by the greatest art of the past, and to study again, "face to face with Nature—to follow it, to watch it, and to copy, closely, faithfully, ingenuously—as Ruskin suggests, choosing nothing and rejecting nothing." The studies of a Pumpkin Flower (Meran), Branch of Vine (Bellosquardo), Cyclamen (Tivoli), reproduced in Chapter III., and others, were made during this autumn of 1856.

In a letter written to Mr. M. Spielmann, a few years before his death, Leighton describes the procedure he pursued in accomplishing a serious work.

"In my pictures,—which are above all decorations in the real sense of the word,—the design is a pattern in which every line has its place and its proper relation to other lines, so that the disturbing of one of them, outside certain limits, would throw the whole out of gear. Having thus determined my picture in my mind's eye, in the majority of cases I make a sketch in black and white chalk upon brown paper to fix it. In the first sketch the care with which the folds have been broadly arranged will be evident, and if it be compared with the finished picture, the very slight degree in which the general scheme has been departed from will convince the spectator of the almost scientific precision of my line of action. But there is a good reason for this determining of the draperies before the model is called in; and it is [13]this. The nude model, no matter how practised he or she may be never moves or stands or sits, in these degenerate days, with exactly the same freedom as when draped; action or pose is always different—not so much from a sense of mental constraint as from the unusual liberty experienced by the limbs to which the muscular action invariably responds when the body is released from the discipline and confinement of clothing.

"The picture having been thus determined, the model is called in, and is posed as nearly as possible in the attitude desired. As nearly as possible, I say; for, as no two faces are exactly alike, so no two models ever entirely resemble one another in body or muscular action, and cannot, therefore, pose in such a manner as exactly to correspond with either another model or another figure—no matter how correctly the latter may be drawn. From the model make the careful outline on brown paper, a true transcript from life, which may entail some slight corrections of the original design in the direction of modifying the attitude and general appearance of the figure. This would be rendered necessary probably by the bulk and material of the drapery. So far, of course, my attention is engaged exclusively by 'form,' colour being always treated more or less ideally. The figure is now placed in its surroundings, and established in exact relation to the canvas. The result is the first true sketch of the entire design, figure, and background, and is built up of the two previous ones. It must be absolutely accurate in the distribution of spaces, for it has subsequently to be 'squared off' on to the canvas, which is ordered to the exact scale of the sketch. At this moment, the design being finally determined, the sketch in oil colours is made. It has been deferred till now, because the placing of the colours is, of course, of as much importance as the harmony. This done, the canvas is for the first time produced, and thereon I enlarge the design, re-draw the outline—and never departing a hair's-breadth from the outlines and forms already obtained—and then highly finishing the whole figure in warm monochrome from the life. Every muscle, every joint, every crease is there, although all this careful painting is shortly to be hidden with the draperies; such, however, is the only method of insuring absolute correctness of drawing. The fourth [14]stage completed, I return once more to my brown paper, re-copy the outline accurately from the picture, on a larger scale than before, and resume my studies of draperies in greater detail and with still greater precision, dealing with them in sections, as parts of a homogeneous whole. The draperies are now laid with infinite care on to the living model, and are made to approximate as closely as possible to the arrangement given in the first sketch, which, as it was not haphazard, but most carefully worked out, must of necessity be adhered to. They have often to be drawn piecemeal, as a model cannot by any means always retain the attitude sufficiently long for the design to be wholly carried out at one cast.[2] This arrangement, is effected with special reference to painting—that is to say, giving not only form and light and shade, but also the relation and 'values' of tones. The draperies are drawn over, and made to conform exactly to the forms copied from the nudes of the underpainted picture. This is a cardinal point, because in carrying out the picture the folds are found fitting mathematically on to the nude, or nudes, first established on the canvas. The next step then is to transfer the draperies to the canvas on which the design has been squared off, and this is done with flowing colour in the same monochrome as before over the nudes, to which they are intelligently applied, and which nudes must never—mentally at least—be lost sight of. The canvas has been prepared with a grey tone, lighter or darker, according to the subject in hand, and the effect to be produced. The background and accessories being now added, the whole picture presents a more or less completed aspect—resembling that, say, of a print of any warm tone. In the case of draperies of very vigorous tone, a rich flat local colour is probably rubbed over them, the modelling underneath being, though thin, so sharp and definite as to assert itself through this wash. Certain portions of the picture might probably be prepared with a wash of flat [15]tinting of a colour the opposite of that which it is eventually to receive. A blue sky, for instance, would possibly have a soft, ruddy tone spread over the canvas—the sky, which is a very definite and important part of my compositions, being as completely drawn in monochrome as any other of the design; or, for rich blue mountains a strong orange wash or tint might be used as a bed. The structure of the picture being thus absolutely complete, and the effect distinctly determined by a sketch which it is my aim to equal in the big work, I have nothing to think of but colour, and with that I now proceed deliberately, but rapidly."

So far Leighton explained the conscious processes he went through in creating his pictures; but does this explanation record truly the real agencies which brought about the result we see in his finest achievements? I should say no,—most emphatically no. Where we can trace the sign of these processes, there the picture fails in the power of convincing. No such process produced "Eucharis" nor the "Syracusan Bride." The process may have been gone through in painting the procession, but it is obliterated by touches instinct with a true painter's inspiration. All teachable qualities Leighton could teach on the lines of soundest principles. His extreme modesty left others to find out that where his preaching left off the real work began in his own pictures. No one knew better than Leighton that no theoretic knowledge ever made an artist; no teachable processes ever made a beautiful picture; no one knew better that head without heart never produced any work that was truly cared for.

"God forgive me if I am intolerant," he wrote to Steinle, "but according to my view an artist must produce his art out of his own heart; or he is none."

were the words with which he ended his first address to the students of the Royal Academy.

[16]In the world's estimate of things and people, classification plays at times a pernicious part. Classification in art matters may be tolerated as useful only in the education of the non-artistic. Invariably the most convincing touches escape the possibility of being reduced to so dull a process of reckoning. Art marked by individual spontaneity, emanating from the ego of the artificer, refuses to be levelled down into a class. Critics seem at times to be strongly tempted to fit an artist's achievements into certain classes, because they have previously made up their minds as to the class the work belongs to. Hence the perversion often of even an intelligent critic's estimate: certain squarenesses exist which will not fit into round holes, so, for the sake of classification, the corners must be shaved off. Surely no artist ever existed who evaded being comfortably fitted into either a square or a round hole more completely than did Leighton. Every serious work he undertook was an entirely separate performance from any previous invention—a new venture throughout—and, once decided on, carried through with absolute conformity to the original conception. Therefore any classification, beyond his mere method of working, is more sterile in producing a just estimate of Leighton's art than of those workers who are in the habit of painting pictures in which the same motive recurs. Essentially original in his conceptions as in his aims, and vibrating with receptiveness, he sounded nevertheless every impression he received by unchanging principles adhered to as implicit guides. He had within him at once the steadiest rock as a foundation, and the most fertile of serial growths on the surface. Abiding rock and surface flora alike had had their earliest nurture, it must be remembered, in foreign parts, under other skies than that of our veiled English light—under other influences of nature and of art than that of our English climate and schooling—and it is partly owing to this fact that it is not realised by those who have never seen nature under the aspects [17]which most delighted him, that Leighton's conceptions were directly and invariably inspired by nature. Those who are conversant with Italy and other Southern countries will possess the key to much that is misjudged by others in Leighton's work. Scenes which entranced his sensibilities as a boy, and, lingering ever in his fancy, gave subjects for his paintings when his art was mature, may appear to one without special knowledge of the South as mere echoes of classic art. When he was thirty-one Leighton exhibited the picture "Lieder ohne Worte."[3] It is no record, probably, of any particular place, nor of any particular fountain; but when strolling on a road in or near a southern town or village in Italy, a view which might originally have inspired the motive may be seen at any moment. Encased in a wall near Albano is a fountain which certainly recalled to me the picture as, in the bright light of a May morning, the song of nightingales in the grand foliage of overhanging magnolia trees echoed the sound of the water springing from the glistening lip, and flowing over the clean curve of the marble basin into the trough below. There was the same lion's head which served as spout, the same arrangement of ornament encircling it; also a finely shaped pitcher placed below to catch the water, and—more recalling than any detail—was the echo of the real motive of the picture—the dream-like poetry of the sunlit scene, with the musical accompaniment of trickling water. Had Leighton painted a Discobolus, it would probably never have occurred to most English critics that nature and living action had inspired the work. Above the lake of Albano is a road—"the Upper Gallery"—where every day are to be met men playing the game. Any one watching it may see repeated over and over again the action in the well-known statue. Nature inspired the creations of the great ancients, and [18]it was also invariably first-hand impressions from nature that inspired Leighton's creations, whatever superstructure of learning he added in the course of their development. Living in Italy when his feelings were most sensitive to impressions, the origin of the suggestions he imbibed is to be found in her atmosphere, colouring, and the scenes which surrounded him when his imagination was most free and fertile. Later, when he lived in England, his travels in Italy and Greece supplied him with the subjects for the most beautiful sketches he made direct from nature. No one, I believe, has ever painted the luminous quality of white, as it is seen under heated sunlight in the South, with the same charm as Leighton. The sketches he made of buildings in Capri[4] are quite marvellously true in their rendering of such effects. He made equally beautiful studies of mountains and sea, under the rarefied atmosphere of Greece. He seemed always happiest, I think, when the key of his pictures and sketches was light and sunlit; in such pictures, for instance, as "Winding the Skein," "Greek Girls Picking up Shells by the Seashore," "Bath of Psyche," "Invocation," and others remarkable for their fairness and their light, pure tone.

Leighton's sympathies were adverse to the more sensuous qualities in painting. Often, in discussing the works by Watts, he would strongly discourage those who were, he considered, unduly influenced by the charm of the great painter's quality and texture, from endeavouring to aim at it in their own work. Such a treatment, Leighton maintained, might be legitimate as the natural expression of the intuitive genius of one gifted individual, but was not the treatment to copy by the student on account of any intrinsic merit. He had almost an aversion to any process which obtained effects through roughness and inequality of surface. His genuine youthful predilection, which [19]he retained consistently throughout his life, was for the early Italian art and Italian method of painting al fresco. "To see the old Florentine school again is a thing which always enchants me anew, for one can never be sated with seeing the noble sweetness, the child-like simplicity, allied with high manly feeling, which breathes in it. But I speak to you of plain things which you know far better than I."—(Letter to Steinle from Florence, 1857.)

GREEK GIRLS PICKING UP SHELLS BY THE SEASHORE. 1871

By permission of The Right Hon. Joseph ChamberlainToList

After Leighton became President of the Royal Academy he made Perugia his halting-place for some weeks during his autumn travels, while he wrote his biennial discourses for the students. He invariably stayed at the well-known Brufani Hotel,—Mrs. Brufani, with whom he made great friends, always reserving the same two rooms for him, from the windows of which he could watch the sun set behind the glorious piles of Umbrian mountains to the west of Perugia. From these windows he also made sketches in silver point of the distant ranges, each form modelled with exquisite delicacy and perfection, though in faintest tones. Other inmates of the Brufani supposed he lived in his two rooms, as he was seldom seen elsewhere in the hotel; but Leighton had found a restaurant which, like his old quarters in Rome—the Café Greco—was the resort of the artists living in Perugia. There he would lunch, and then repair to the Sala del Cambio. Sitting on the raised seat near the window, he would, day after day, spend an hour or more revelling in the beauty of the frescoes by Perugino. Then he would mount to the Pinacoteca and take a deep draught of enjoyment from the tempera paintings of Perugino's master, Benedetto Bonfiglio, Leighton's favourite of favourites ("They are all my Bonfigli!" he would exclaim), whose angels' aureoles rest on wreaths of roses, and whose lovely work Perugia seems to have monopolised. The old paintings of Martino, Gentile da Fabiano, Pietro da Foligno, and their [20]followers Leighton also loved, likewise the later work of Bernardino Pinturicchio and Lo Spagna, pupils with Raphael of Perugino. Among his greatest favourites were the painted banners—the Gonfalone—which are peculiar to the Umbrian cities. He loved the freshness of their quality—the result of a first painting never retouched—the masterly ease of the workmanship, full of tender, gracious beauty. These days were Leighton's real holidays, where, in rapturous admiration of the art he loved so profoundly, he put behind him for the time the weight of official responsibility, and the no less exhausting social duties of his life.

Had Leighton been able to devote himself to the method of painting in fresco, and to work in a warm, dry climate, which admits of painting into the wet surface of plaster without danger of the wall retaining the moisture, he would, undoubtedly, have felt a freer impulse to work rapidly and more spontaneously than when his touch was controlled by the complicated procedures in oil painting. In the process of painting al fresco, colour, in a sense, models itself—its absorption into the wet plaster softening the edges of one touch into another; hence, over a first painting no half obliteration is necessary, and any elaborate finish is avoided. Being obliged to complete before the plaster was dry, Leighton could not have yielded to the temptation to over-refine his surface; and his splendid power as a draughtsman, allied to his sense of beauty, would have found a perfectly spontaneous, happy utterance. As a boy he had imbibed one great principle, and from this principle he never deviated. He wrote, "The thoroughness of all the great masters is so pervading a quality that I look upon them all as forming one aristocracy." In his sketches alone did Leighton relax from the strain which absolute thoroughness involves; and then, in all the fervour of æsthetic inspiration, colour would fly on canvas, chalk or paper, with a charm of quality and [21]exquisite grace of line and form which, as Mr. Briton Rivière remarks, is the very best that can be obtained from a great artist thoroughly trained, but which condition Leighton would never admit into what he considered his serious work. He writes to his father from Rome, January 1853: "I was deeply impressed with the glorious works of art I saw in Venice and Florence, and was particularly struck with the exquisitely elaborate finish of most of the leading works by whatever master; the highest possible finish combined with the greatest possible breadth and grandeur of disposition in the principal masses. Art with the old masters was full of love, refined,—sterling." Leighton formed his standard from these old masters, and never for a moment allowed his standard to be replaced by another. In certain types of Englishmen chivalric loyalty develops at times into obstinacy. Leighton, with all his passion for Italy, his artistic sensitiveness, his excitability, his finely wrought nervous temperament, and his intense power of sympathy, had also in his blood something of the old English Tory, which made him adhere and remain loyal to the strongest impressions of his youth. Catholic and generous as he always proved himself to be when it was a question of considering the work of others, when he was considering his own he ever maintained absolute consistency with the tenets of his early illuminations. Speaking of his extraordinary sense of duty and the consequent tension involved, Mr. Briton Rivière writes:—

"No doubt the constant wear and tear occasioned by the perpetual strain of mental and physical watchfulness did much to shorten his life; I think it sometimes injured his own work as an artist, because, though a great artist can never be evolved except by years of patient work and strenuous effort to do his very best always, yet, on the other hand, it is often the happy, easy work and absolutely spontaneous effort of the moment by such a hand which is his very best. Such happy, easy work [22]probably Leighton would seldom allow himself to do, and never would leave at the right moment, but would still strive to make better and more complete. He must still elaborate it and try to make it more perfect; and this it was that made his enthusiastic admirer Watts sometimes say, 'How much finer Leighton's work would be if he would admit the accidental into it.'"

A fact, little suspected by the public, certainly affected the element of strength in some of Leighton's works. Besides often suffering from a positive want of health, his normal physical condition was far from robust; and, as appears in his letters, he suffered much through weakness and irritation in the eyes from the time he was a boy. He did not wear his physical (or any other) distress on his sleeve, and experienced many hindrances in his work never dreamt of, even by his intimate acquaintances. These might not have been so serious had he been willing to sacrifice all other duties in life to his own special vocation; but though he realised that Art, the language of beauty, was his main passion, his conscience would not allow him to make this passion an excuse for avoiding help to his generation on other lines, if he distinctly felt he could do so. In the happiest of surroundings, with his life unburdened by public responsibilities, he painted "Cimabue's Madonna"; and, for pure vigour in the manipulation, this painting has a robust quality which is scarcely to be found in any other of the larger works which followed, though these may possess many other virtues, and evince a more definite individuality, than does the early work.

Leighton's art appeals to the artists (comparatively few in England) possessed of cosmopolitan culture—also to many who love beauty, a sense of refined distinction in feeling and in form and in the arrangement of line. Beyond these it appeals also to the great public outside the radius of specialists, a public which is impressed by a sense of beauty [23]and achievement without possessing the knowledge of experts. It is not much cared for by the disciples of either of the latest schools in England, and in France, which have governed fashion in the matter of taste for the last twenty years. In the first place, it appeals but little to those to whom the highest province of art appears to consist in conveying didactic sentiments and poetic ideas through a language of form and colour—to suggest thought to the brain rather than beauty to the eye. Respecting this theory of the province of art, Leighton expresses himself clearly in his second address to the Royal Academy students in December 1881:—

"Now the language of Art is not the appointed vehicle of ethic truths; of these, as of all knowledge as distinct from emotion, though not necessarily separated from it, the obvious and only fitted vehicle is speech, written or spoken—words, the symbols of ideas. The simplest spoken homily, if sincere in spirit and lofty in tone, will have more direct didactic efficacy than all the works of all the most pious painters and sculptors from Giotto to Michael Angelo; more than the Passion music of Bach, more than a Requiem by Cherubini, more than an Oratorio of Handel.

"It is not, then, it cannot be the foremost duty of Art to seek to embody that which it cannot adequately present, and to enter into a competition in which it is doomed to inevitable defeat."

That so great a painter as Watts should have taken a contrary view, and preached this contrary view as that which inspired his own conscious aims, was quite sufficient to secure to it many adherents. He preached his doctrine, moreover, with a most convincing argument, but one which cannot logically be used in favour of it, namely, his own great genius as a painter. Watts was essentially a painter—one who at his best ranks with the best painters of all times.

Mr. Arthur Symons, writing on "The Psychology of [24]Watts,"[5] quotes a popular preacher who affirmed that "Critics who approach his (Watts') work from the side of technical excellence do not interest him at all. His endeavour has been to make his pictures as good as works of art as was possible to him, for fear that they should fail altogether in their appeal; but, beyond that, their excellence as mere pictures is nothing to him." "Now," writes Mr. Symons, "it is quite possible that Watts may have really said or written something of the kind; he may even, when he set himself down to think, have thought it. The conscious mental processes of an artist have often little enough relation with his work as art; by no means is every artist a critic as well as an artist. But to take a great painter at his word, if he assures you that the excellence of his pictures 'as mere pictures' is nothing to him; to suppose seriously that at the root of his painting was not the desire to paint; to believe for a moment that great pictorial work has ever been done except by those who were painters first, and everything else afterwards, is to confuse the elementary notions of things, hopelessly and finally. And so, when we are told that the technical excellence of Watts' pictures is of little consequence, we can but answer that to the 'painter of earnest truths,' as to all painters, nothing can be of more consequence; for it is only through this technical excellence that 'Hope,' or 'The Happy Warrior,' or 'Love and Life,' is to be preferred to the picture leaflet which the district missionary distributes on his way through the streets."

All who knew Watts intimately and watched him working day by day can testify that he spared no labour, time, or patience, in working over and over on a picture in order to attain the finest quality in the actual surface which his material—paint—could possibly produce.

Neither the disciples of the original brotherhood of the [25]pre-Raphaelites nor those of Burne-Jones care, as a rule, for Leighton's art. Though starting as one with the pre-Raphaelites, Burne-Jones, possessing a remarkably fine intellect, a subtle fancy, a rich inventiveness in the detail of design, an exquisite sense of grace, and great genius as a colourist, developed so distinct an individuality that his followers cannot be precisely identified with those of the pre-Raphaelites. Leighton fully appreciated the genius of Burne-Jones, and did all in his power to secure his adherence to the Academy; but he had no sympathy for that feeling in art evinced by Burne-Jones' followers, which is so essentially rooted in purely personal moods that even distortion of the human frame is condoned, so long as prominence is given to the suggestion of such moods.

Imbued with a rare, peculiar refinement all its own, a kind of æsthetic creed sprang up in the later days of the nineteenth century apart from the arid soil of commonplace respectability and tasteless materialism. Burne-Jones painted it, Kate Vaughan danced it, Maeterlinck wrote it, the "Souls" (rather unsuccessfully) attempted to live it, the humourists caricatured it, the Philistines denounced it as morbid and unwholesome. Leighton was tolerant and amused, but could not be very solemn over it. And, assuredly, already this creed has been whisked away into the past by fashions diametrically opposed to it in character. Its text may be found in Melisande's reiterated refrain, "I am not happy"—though the unhappiness does not seem ever to have been of the nature of the iron which entered into the soul, but rather the shadow of sadness, adopted with the idea that such a condition betokens a more rare and tender grace than the radiance of joy can give. Every mood of the subjective has been lately in fashion in æsthetic circles, and is still rampant in much of the up-to-date (or down-to-date, as it may be) conditions of the present [26]taste. This is probably consequent on the leadership of those artists who possessed not only genius and sense of beauty, but a peculiar charm of texture in their work which seems a native adjunct to certain temperaments. It is a purely personal manner, and crops up without reference apparently to any special school of art. In Sodoma we find it allied to a development of the splendid completeness of Italian Art; again in the Celt, Watts, to a lofty imagination and to a Pheidian sensibility for noble form; it appears in the work of the Jew, Simeon Solomon; and is an element in Burne-Jones' lovely quality of painting especially noticeable in his water-colour drawings—and, on a smaller scale of workmanship, in the pictures by Pinwell. It is more a matter of quality than of colour, and yet it is only colourists who have possessed it—most obviously, however, where the key of colour is restrained almost to monochrome. A hint of it can be found in Tintoretto's paintings, where few positive tints are prominent, as in some of the ceiling paintings in the Ducal Palace at Venice. There is a something which this special handling suggests which possesses a very subtle charm, the charm of dreamland,—less tangible, less real than direct appeals from nature. A slight mystery seems to veil the vision like a reflection swayed by the surface of the water. It is less explicit than any real object, and only suggests completion without quite achieving it; there is something left out from the aspect of nature, something added from the ego of the artist. There are those to whom such a treatment suggests a deeper truth than can any wholly explicit expression, because they feel forcibly that mystery is the soul of all earthly conditions—"we see through a glass darkly." There are others—and Leighton was among these—who are so strongly imbued with a sense of the wonderful and marvellous in actual creation that they need no art, no veiled suggestion of the hidden, in [27]order to realise that our lives are wrapped in mystery from the cradle to the grave. This quality in painting alluded to, fits in with that taste in literature which prefers hints to assertions—that insistency on the value of what is, after all, but a fugitive phase in special temperaments—that setting most value on the principle of suggestion rather than of definition, of which we hear so much. The devotees of Maeterlinck delight in the shadow of a thought rather than the thought arrêté; they feel that a further stage of refined culture is reached in worshipping a style you have to get somehow behind, rather than one in which thoughts are fully and frankly expressed. Doubtless it requires a more subtile weapon to catch the fleeting aroma, the hint of a thought trembling in the brain and giving it permanent existence in Art, than to carve the expression of a complete idea explicitly with cameo-like precision, be it in the form of words or a visual impression—the wise sayings of a Solomon or a Bacon, the sculpture of a Pheidias or the painting of a Leonardo da Vinci. The actual visible facts in the aspects of nature, which were of such entrancing interest to Leighton, become of less and less interest to the wide public as the human intelligence is trained more and more through books, less and less through the eye; our modern conditions making the world we live in, more and more ugly and uninspiring to the echoing tune of nature within us. Even if we recede into the depths of the country, we find the signs all round us of the sense of beauty being deadened, the revulsion against ugliness having ceased—corrugated iron supplanting thatched roofing, and the loveliest, most rural spots in England year after year newly deprived of some special charm they have possessed for centuries. Those who seek for beauty have been led to find it in the unreal—the things which might be, but are not. We cannot help it, but we certainly become more artificial as [28]our civilisation becomes more complicated, and everything we see around us grows uglier. It is because the general public has so little genuine interest in Art or love of beauty, however great may be its professions, that the tendency has developed to care for the art which appeals rather to the mind and the æsthetic sensibilities generally, than to the actual vision.

This reign of the subjective has brought in its train the undue monopolising of the world's most ardent interest in one passion. French novels of great literary power secured to it the monopoly in France, and magnates in æsthetic culture have grafted it on to our English taste. This strongest and most beautiful feeling in human nature has been so monotonously forced upon us in literature à tort et à travers—the assumption that this is the only feeling worth serious consideration has been dwelt on with such a tiresome pertinacity—it has been so often caricatured, so often debased in books and pictures, that even the real thing itself runs a danger of palling. This human passion may be the greatest, but it is not the only great feeling with which the lives of men and women are enriched; and surely the absorbing prominence which has been given to it latterly in literature is out of proportion with its real position in healthy lives. Little sympathy seems left for other deep and stirring emotions. In Leighton's art we find no monopoly of this kind either recorded or suggested. He painted the passion of lovers in the "Paolo and Francesca," but with no more sincere interest than he did other feelings; than, for instance, his fervent and reverent worship of art in "Cimabue's Madonna," or in the ecstasy of joy in the child flying into the embrace of her mother in "The Return of Persephone," or in the exquisite tender feeling of Elisha breathing renewed life into the Shunammite's son, or in that sense of rest and peace after struggle in the lovely figure of "Ariadne" when Death releases her from her pain; or in the yearning for that peace [29]in the "King David": "Oh that I had wings like a dove! for then would I fly away and be at rest."

As the climax of nature's loveliest creations Leighton treated the human form with a courageous purity. In his undraped figures there is the same total absence of the mark of the degenerate as there is in everything he did and was; no remote hint of any double-entendre veiled by æsthetic refinement, any more than there is in the Bible, the Iliad, or in the sculpture of Pheidias.

To quote lines that were written about Leighton very shortly before his death:—

"There is truly to be traced in the feeling of his art that 'seal on a man's work of what is most inward and peculiar in his moods'; the sign of individual intimate preferences and of the moving power which certain aspects of beauty have had upon the artist's innermost susceptibilities, though these may be somewhat veiled and distanced by being translated through the reserved form of a classic garb. Perhaps it is this reserve which invests Sir Frederic Leighton's art with the special aroma of poetry which Robert Browning found in it to a greater extent than in any other work of his time.[6] Whether in his larger compositions, in the complicated grouping of many figures, such as the Cimabue picture being led in procession through the streets of Florence, the 'Daphnephoria,' 'Heracles struggling with Death,' the 'Andromache,' the 'Cymon and Iphigenia,' and others; or those simpler compositions, such as the 'Summer Moon,' 'Wedded,' 'The Mountain Summit,' 'The Music Lesson,' 'Sister's Kiss,' in all can be traced the sentiment of a poet inspiring the touch; not overriding by any assertiveness of sentiment the complete scheme of the picture, but lingering here and there with a wistful loveliness which has to be sought for within the barriers of the formal classic design. And it is this reticence in the expression of individual sentiment, this subduing it to the [30]larger conditions of a more abstract style of art which, though it will never make Sir Frederic Leighton's work directly popular, gives to it a quality of distinction. In such reticence is an element of greatness which probably will only be duly appreciated when the more transient moods of thought in the present generation have passed. His work lacks altogether the sentimental, brooding-over-self quality, which, when allied to genius, is contagious, and gives an interest of a subtle, but perhaps not altogether wholesome kind to some of the best work of this era."

And again after his death:—

"Beauty of every kind played on a very sensitive instrument, when it made an appeal to his nature, giving him very positive joy: no complication of subtle interest beyond the actual influence being required before a responding echo was sounded, because so pure and innocent was this joy he had in the charm of beauty;—so also attendant on his personal influence, there was no power of mesmerism, nor of the black arts. In every direction it was healthy and bracing. Even a Nordau could have discovered no remotest taint of the degenerate!"

It is the emotions which art suggests outside itself which have been viewed by one school as more interesting than art itself, and it is the sensuous qualities in painting—colour and texture—which are the visible agents, and convey more readily these suggestions of emotions in our northern temperaments than do beautiful lines and forms. Our northern temperaments also love symbolism and mysticism, therefore are apt to favour the art that meets a veiled condition of things; and the perfection of complete finish in nature's form is no longer held up as a standard for the student to aim at. Leighton had no sympathy with the artificial, neither had he any with the shadow put in the place of the substance. The actual was ever sufficient for him, for in nature herself he never failed to find sufficient inspiration. The mind of the Creator in matter is what the ingenuous artist temperament [31]searches for and is inspired to record; whereas it is, on the one hand, phases of human moods, selections from human passions, good, bad, and indifferent, which are made to saturate the feeling in much of our modern art, or, on the other hand, aspects of nature's moods given without the framework of her structure, and without the detail of her perfection.

It may be argued, however, that there are among the most beautiful effects in nature those which are not fully distinct to the sight—the shimmering iridescence on a shell, where one colour is seen sparkling against another through a film, or the waving branches of a willow, the liquid shifting of a flowing stream, or the endless effects of cloud and mist in a northern sky. To express this in paint requires an appropriate treatment in the manipulation of the pigment itself. Watts' theory was that you have to unfinish the record of certain facts in order to render the truth of the whole fact (see also Steinle's criticism on Leighton's head of "Vincenzo," 1854). He would, therefore, film his painting over with a scumble of white, and only partially repaint the surface, in order to get at that whole truth which includes the bloom of atmosphere and the veil of northern mists. Leighton is thought at times to have erred on the side of explicitness, and the texture of his surface is apt undoubtedly to lack the vibrating quality which carries with it a beauty of its own. This is partly accounted for by the fact that he had imbibed the rudiments of his teaching in a school whose followers were not sensitive to the finest qualities in oil painting, but also probably from his extreme desire to give expression to his sense of the intense finish in nature.

Doctrinaires of the very latest fashion in art insist that nothing comes legitimately within the province of the pictorial, except the impression of nature transmitted to the physical organ detached from memory, experience, and mind. By this faction the eye is treated solely as a machine. Sound [32]as may be the doctrine that art has nothing to do with what the eye cannot see, or with those facts which experience alone teaches us are there, it is also no less true that the human eye sees, according to its intuitive power of transmitting to the brain, the different component parts of the actual object of its vision. It was no knowledge of anatomy which enabled Pheidias to see every subtilty of form in the human figure with consummate insight—any more than it was a knowledge of the laws of the flow and ebb of the tides, which enabled Whistler to give an actual sense of the swaying surface of the waves in "Valparaiso Bay"; again, it was no knowledge of botany which enabled Leighton and Millais to reproduce the structure of plants so perfectly, that they evoked unmitigated admiration as botanical studies from so high an authority on botany as Sir W.C. Thistleton Dyer. We may be told that what we really see is only the relation of tone, of light and shadow; but the fact that the architecture of the whole visible world, the meaning-full construction of all things that nature builds, is being constantly realised by our sight, makes the truth of this theory at least doubtful. That our eye cannot discern these natural objects without light goes without saying; further, that light and shadow shape the forms to be rendered by the brush is also true: but the assertion that what we see is only light and shade playing upon form, is shutting the door on another equally obvious truth. The eye, gifted with a natural sense of form, records ingenuously to the brain the sense of projecting and receding planes, the foreshortening of masses, the straightness, slant, or curve in a surface or in a line. A complete and exhaustive result may be achieved in a painting through this sense of form, as in the work of Van Eycke and of Leonardo da Vinci; or a shorthand record may be made, as in that of Phil May's sketches. But we feel that in both the sense of the whole [33]form has been felt. However, volumes would not exhaust the arguments for and against the so-called impressionist's view of art; so-called—but surely a term unfortunate and misleading, and in nowise explanatory. Every touch a true artist ever puts upon canvas is a record of an impression—whether that impression comprises the structure, light and shade, true colour and tone, all combined,—or only certain surface qualities extracted from its entirety and enforced so that the most obvious appearances start into relief, giving doubtless a sense of vitality to a work, but remaining nevertheless only a partial record of the object. Needless to say, Leighton sought to record his impressions of nature in their entirety, and this necessitated a balancing of their component attributes. The startling element is never found in his art.

He viewed the influence of art as one which should perfect the life of every class; should purify in all directions the debasing elements of materialism and self-interest; should put zest and gratitude into the hearts of all men and women who can see and feel, by awakening a sense of the perfection and beauty of nature, art forming an explanatory and illuminating link between her and mankind—a translation of her perfection transmitted with all reverence by the artificer;—a perfecting beautiful pinnacle in the erection and development of a noble human being.

No words could better describe Leighton's high endeavour in training his own mind and those whom he tried to influence, than the following, written by Lord Acton and quoted by his friend, Sir M. Grant Duff.[7] "If I had the power," writes Sir M. Grant Duff, "I would place upon his monument the words which he wrote as a preface to a list of ninety-eight books he drew up, and about which he still hoped to read a paper at Cambridge when he wrote to me on the subject last autumn. 'This list is submitted with a view to assisting an English [34]youth, whose education is finished, who knows common things, and is not training for a profession, to perfect his mind and open windows in every direction; to raise him to the level of his age, so that he may know the forces that have made the world what it is, and still reign over it; to guard against surprises and against the constant sources of errors within; to supply him both with the strongest stimulants and the surest guides; to give force and fulness, and clearness and sincerity, independence and elevation, generosity and serenity to his mind, that he may know the method and lay of the process by which error is conquered and truth is won, discerning knowledge from probability and prejudice from belief; that he may learn to master what he rejects as fully as what he adopts; that he may understand the origin as well as the strength and vitality of systems, and the better motives of men who are wrong; to steel him against the charm of literary beauty and talent, so that each book, thoroughly taken in, shall be the beginning of a new life, and shall make a new man of him.'" In a like spirit Leighton sought to arrive at viewing art; and what Lord Acton sought to effect by the general culture of men's minds and natures through reading, Leighton sought to effect in his special vocation by inducing other artists to study all that was greatest in Art from a wide and unprejudiced point of view—making it their own, so to speak, by thoroughly realising and appreciating the qualities in it which make it great. Each true masterpiece in Art, he urged, should be thoroughly taken in, and should be the beginning of a new effort. On the other hand, he sought to make the student "learn to master what he rejects as fully as what he adopts, that he may understand the origin as well as the strength and vitality of systems, and the better motives of men who are wrong." His desire was to guide art into the current of the world's best interests—the current in which good [35]literature is so forcible an agent—on the highest, broadest, most catholic lines. He endeavoured to do so by his example as a working artist, by his Discourses, by his labours for the public in every direction where the Art of his country was concerned, and more directly by his influence on those with whom he personally came in contact.

[1] This picture has, I believe, unfortunately left the country. It was suggested by a passage in the second Idyll of Theocritus: "And for her, then many other wild beasts were going in procession round about, and among them a lioness." Sketches for portions of the picture and the squared tracing for the complete design can be seen in the Leighton House Collection. The full-length portrait of Mrs. James Guthrie was exhibited the same year as this second processional picture, which appeared on the walls of the Academy eleven years after the "Cimabue's Madonna." The head of the central figure, the Bride, Leighton painted from Mrs. Guthrie. The following charming letter from Mrs. Norton, the most notable of Sheridan's three beautiful daughters, refers to this picture:—

3 Chesterfield Street,

April 9.

Dear Mr. Leighton,—I was so amused by the little grandson's observation on the picture that I cannot help writing about him. I asked him "what he thought of it"? He said, "Oh! it was beautiful! but you told me it would be beautiful—Mr. Leighton was like a man in a story! you did not look so much at him as Carlotta and I did, but I suppose you have seen him before, and you did not seem to pity the little panther! There was, in the picture, a little young puppy panther, and one of the young brides was coaxing it so tenderly, and looking down at its head; and she was one of the prettiest and kindest looking of all the brides (it was the side of the picture furthest from the screen); and I could not help thinking, 'Ah, my poor little panther! you little know when the brides get into that temple, and she gets married, how she'll forget all about you, and get coaxing other things, her husband and her children'; and I felt quite sorry for the panther." So spoke my grandson (just as I felt sorry for the cripple beggar).

Now, as I am quite sure no one else will take this view of what is the principal interest in your glorious procession of youth and hope, I thought it as well to let you know, that you might give that little panther his due importance (a little leopard, I think he is), and not suppose him a subordinate accessory! That whole procession was tinged with mournfulness in Richard Norton's eyes for that little leopard's sake. I shall see that "Dream of Fair Women" again in the Exhibition, and admire it, as I did to-day, in a crowd of other admirers, I know. I do not mind the crowd. I see over them and under them, and through them, when there is anything so worth being eager about.—Believe me meanwhile, yours very truly,

Caroline Norton.

[2] In a letter from Leighton to his mother, the following sentence occurs:—"Will you please explain to him" (his father) "that I am not going to model the drapery of my figures, but the figures themselves to lay the drapery on, as my models could not fly sufficiently long for me to draw them in the act; it is of course a very great delay, but the result will amply make up for the extra trouble, I hope."

[3] The picture has left the country, but sketches of the complete design are among those in the Leighton House Collection.

[4] Lent by Lady Wantage to the Exhibition, in Leighton House, of the smaller works and sketches in 1903.

[5] Outlook, July 15th, 1905.

[6] When standing with me before Leighton's picture "Wedded" in the studio Robert Browning exclaimed, "I find a poetry in that man's work I can find in no other."

[7] "The Late Lord Acton." The Spectator, July 5, 1902.