|

|

Artist Index  The Life, Letters and Work of

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| ANTECEDENTS AND SCHOOL DAYS, 1830-1852 | 34 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| ROME, 1852-1855 | 91 |

| CHAPTER III | |

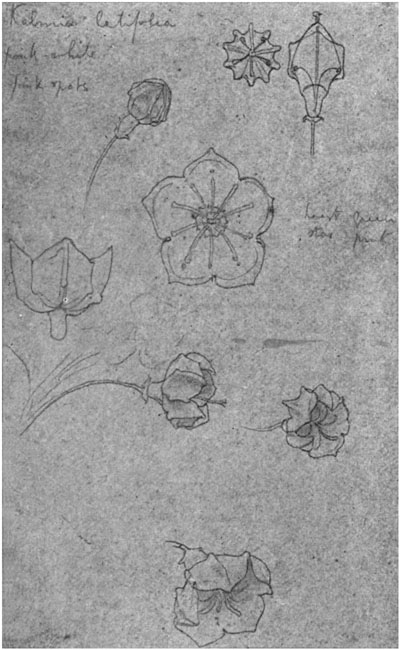

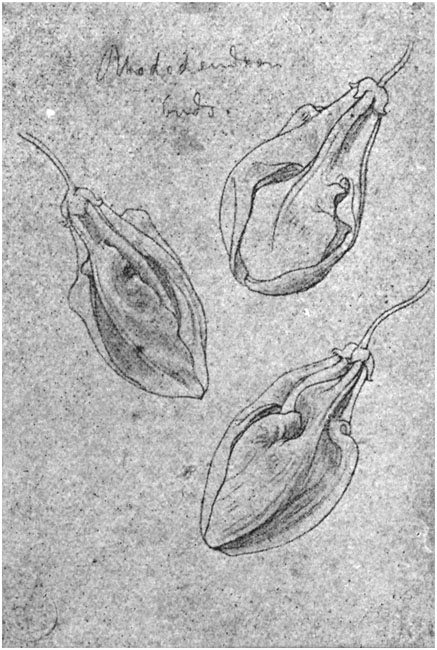

| PENCIL DRAWINGS OF PLANTS AND FLOWERS, 1850-1860 | 197 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| WATTS—SUCCESS—FAILURE, 1855-1856 | 222 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| FRIENDS | 250 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| STEINLE AND ITALY AGAIN—FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF THE EAST, 1856-1858 | 278 |

Motto facing Title-page, line 3, for "from," read "for."

Page xx, No. 49, for "Figures for Ceiling, &c.," read "By kind permission of Sir A. Henderson, Bart."

Page 31, line 7, for "at all," read "to all."

Page 60, omit note.

Page 67, line 31, for "unscorched," read "sunscorched."

Page 103, line 31, for "worse that," read "worse than."

Page 127, line 16, for "Wasash," read "Warsash."

Page 169, line 8, for "Pantaleoni," read "Pantaleone."

Page 197, note, for "Vol. I.," read "Vol. II."

Page 213, lines 6,7, for "owing ... from," read "owing ... to."

Page 265, note. The reference number should be to "Edward," instead of to "Adelaide."

Page 296, line 17, for "Couture," read "Conture."

In 1860, when Leighton, at the age of thirty, definitely settled in England, art was alive in two distinctly new directions. Ruskin was writing, the Pre-Raphaelites were painting, and Prince Albert, besides encouraging individual painters and sculptors, had, through his fine taste and the exercise of his patronage in every branch of art, developed an interest in good design as it can be carried out in manufactures and various crafts. Leighton followed the Prince Consort's initiatory lead; and, by showing the same cultured and catholic zeal in her welfare, was enabled to continue and develop Prince Albert's important work, thereby widening and elevating the whole outlook of art in England.

It has at times been asserted that Leighton was greater as a President of the Royal Academy than he was as a painter. It would be truer, I think, to say that it was because he was so great as an artist in the highest, widest meaning of the word, so sincere a workman, that he stands unrivalled as a President. In a letter to a friend, dated May 1888, ten years after he had been elected President, he wrote, "I am a workman first and an official afterwards," and it was, I believe, because he carried into his official duties the true artist's warmth, sincerity, and zeal for his special vocation, that his influence as an official was never deadened by theoretic red-tapeism, nor by secondary or side issues. Leighton ever [2]flew straight to the mark, and the mark he aimed at in his presidential work was ever the highest essential point from the view he also took as an artist. His official duties, carried out with so great an amount of scrupulous conscientiousness, would have gone far to fill the entire life of an ordinary human being; yet these duties were, to the last, subordinated in his personal existence to his self-imposed duties as a painter and a sculptor.

The words, "I am a workman first and an official afterwards," epitomise the creed of his life. From earliest childhood art had cast over Leighton's nature a glamour which made his heart-service to her the great passion of his life. His "great nature" had in it many sources of stirring interest and of pure delights, which he enjoyed keenly; but nothing came in sight, so to speak, which ever for a moment seriously challenged a rivalry with the salient ruling passion. His character, as it developed, wound itself round it; his strongest sense of duty focalised itself in its service; his ambition ever was more inspired and stimulated by a devotion to the best interests of art than by any purely personal incentive. Leighton was an artist of that true type in whom no influence whatsoever can deter or slacken incessant zeal for work. In the deepest recesses of his nature burnt the unquenchable fire, the paramount longing to follow in Nature's footsteps, and to create things of beauty. Among the many loyal servants who have dutifully worshipped at the shrine of art, never was there one who more completely devoted the best that was in him to her service.

"Va! your human talk and doings are a tame jest; the only passionate life is in form and colour."[1]

Leighton's nature may be viewed from three aspects. Though each aspect is apparently detached from the others, it would be impossible to record a true portrait were the three not kept in view while attempting to draw the picture.

[3]First, there was Leighton, the great man, the public servant, gifted with exceptional powers of intellect and character, who attained the highest social position ever reached by an English artist; the Leighton the world knew, whose sway was paramount in the many councils and assemblies to which he belonged no less than when fulfilling his duties as President of the Royal Academy, and whose helpfulness and zeal in promoting the extension of a knowledge and appreciation of English art in foreign countries and in the colonies became proverbial. Lady Loch tells of his invaluable help in the efforts she and her husband made to encourage art, while the late Lord Loch was Governor of the Isle of Man, of Victoria, and of Cape Colony. "I feel it would be impossible," she writes, "to convey in a few words what a wonderful friend Frederic Leighton was to my husband from the time he first knew him,[2] forty years before Leighton's death, and to myself from the time we married. He was always ready to help us at every turn. Any deserving artist whom we sent to him would be certain to find in him a friend. When we arranged the very small Art Exhibition in the Isle of Man, you could hardly imagine with what energy and thoughtfulness he entered into the matter, impressing upon us all the steps that we ought to take in order to secure its success, even to the details, such as packing and insuring the pictures. He himself sent us pictures for the Exhibition, and guided our judgment in admiring and caring for those which were best and most to be valued, with a paternal care and zeal not describable. Again, when we were in Australia, and the great International Centennial Exhibition in Melbourne took place in 1888, Frederic Leighton selected such a good collection of pictures that they simply were the saving of the Exhibition financially—they attracted such continuous crowds of visitors. Subsequently, when an exhibition [4]of ceramic work was asked for in Melbourne, and Henry Loch wrote to consult his friend, amidst all Frederic Leighton's important work and duties, he rushed about and secured a most interesting collection of all kinds of china and pottery, which was greatly appreciated by the Australians. Again, in 1892, he formed a Fine Art Committee, consisting of himself, who was appointed Chairman, Sir Charles Mills, Sir Donald Currie, M.P., Mr. W.W. Ouless, R.A., Mr. Colin Hunter, A.R.A., Mr. Frank Walton, and Mr. Prange, to select pictures to send for exhibition at Kimberley. Besides a picture lent by Queen Victoria, at Leighton's request, of the portraits of herself and the royal family by Winterhalter, and four by Leighton, which he lent, the Committee secured 181 pictures, though not without great difficulty, Leighton told us, because the artists were afraid their works would be injured by the burning sun, the sandstorms, and the rough journey up from the Cape. Owing, however, to Leighton's untiring exertions, a very interesting and successful exhibition took place in this then little known town of our English colony in Africa."

On the day Leighton died, Watts, his near neighbour and fellow-workman, in a letter to a friend, wrote that he had enjoyed "an uninterrupted and affectionate friendship of five-and-forty years" with Leighton. He continues: "No one will ever know such another. A magnificent intellectual capacity, an unerring and instantaneous spring upon the point to unravel, a generosity, a sympathy, a tact, a lovable and sweet reasonableness, yet no weakness. For my own part—and I tell you, life can never be the same to me again—my own grief is merged in the sense I have of the appalling loss to the nation; it seems to me to be no less."[3] Later, Watts wished it recorded that Leighton's character was the most beautiful he had ever known. This tribute from the great veteran artist, thirteen years Leighton's senior, but who [5]outlived him more than eight years, was echoed far and wide by many at the time of Leighton's death. To his powers and influence, exercised in the Royal Academy as a body and to the members individually, Mr. Briton Rivière, the painter, and Mr. Hamo Thornycroft, the sculptor, give the following appreciative tributes.

Mr. Briton Rivière writes:—

"To begin with, I never really knew him—though we had met several times before—until I began to serve upon the Council with him very soon after his election as President. This at once brought us into very intimate relations, and a very few meetings convinced me that his opinions and actions on that body were invariably regulated by a true spirit of absolute justice and fairness to all, and that if he had his own particular art beliefs—which he certainly had, for art was to him almost a religion, and his own particular belief almost a creed—he never allowed it to bias him in the least. Indeed, I have never worked with any one who exhibited a broader or more catholic spirit of tolerance, even sympathy with all schools, however diverse from his own, only demanding honesty and sincerity should be the basis of each kind of work.

"I have always felt that no one, who had heard only his elaborately prepared speeches, knew his real power as a speaker.

"He was a master of time. I do not think he ever failed to keep an appointment almost to the minute. He was seldom much too early, but never too late.

"He was an ideal president for any institution, and after serving under him for many years, I cannot think of any one faculty which a president should possess, which Leighton wanted."

Mr. Hamo Thornycroft writes:—

"My earliest recollection of Leighton was in 1869, when, [6]with several other young art students, I went to his studio. He had promised to criticise the designs we had made from Morris' 'Life and Death of Jason.' This he did most admirably, it seemed to me, and most sympathetically, devoting considerable time to each; and I came away encouraged and a sworn devotee of the great man.

"For the next few years, I had the benefit of his teaching at the Academy Schools, where he was most energetic as a visitor, and took the greatest pains to help the students. He was, moreover, an inspiring master. Besides doing much for the school of sculpture, till then much neglected, he started a custom of giving a certain time to the study of drapery on the living model. His knowledge in this department and his excellent method were a new element in the training in the schools, and soon had a salutary effect upon the work done by the students. His influence, through the Academy Schools, upon the younger generation of sculptors was very great. There can be no doubt whatever that the rapid advance made in the art of sculpture during the last thirty years was to a considerable extent due to the sympathy and the interest which Leighton gave to it.

"Leighton, as is well known, carefully prepared his important speeches, like many great speakers; but I never saw him fail, or even hesitate, when called upon to speak unexpectedly. At meetings of the Academy Council or at the general assemblies, his summing up and his weighing of the arguments brought forward by members in course of discussion was always masterly, just and eloquent. He had such a great sense of proportion, and detected what was the essence and the essential part of a speaker's argument."

At a meeting held in Leighton's studio, after his death in May 1896, for the purpose of furthering the scheme of preserving the house for the nation as a memorial to the great [7]artist, the sculptor, Mr. Alfred Gilbert, R.A., on rising to speak, said he felt too much on the occasion to be able to make a speech, adding, "I can only say that all I know, and all the little I have been able to do as a sculptor, I owe to Leighton."

In a letter, dated February 9, 1896, Watts again writes: "I delighted in shaping a splendid career of incalculable benefit to his (Leighton's) epoch. His abilities, his persuasiveness, the peculiar range of his cultivation, would have fitted him to accompany a delicate embassy, where his efficiency would have been made evident, establishing a right to be entrusted with the like as its head; I believe something of this and more, if there could be more, was for him in the future. You know, I always looked forward to his seat in the House of Lords. That came about, and I believe the rest was but a question of time. Feeling this, you can understand that my own grief seems to me to be selfish. I am glad you enjoyed the friendship of one of the greatest men of any time."

In the speech which the King, then Prince of Wales, made at the first banquet held after Leighton's death, on May 1, 1897, His Majesty referred to the late President in the following words:—

"All of us in the room, and I especially, must miss one whose eloquent voice was so often heard at this banquet—a voice, alas! now hushed for ever. It is unnecessary, as it would be almost impertinent in me, to hold forth in praise of the merits and virtues of Lord Leighton. They are known to you all. He has left a great name behind him, and he himself will be regretted not only by the great artistic world, but by the whole nation. I myself had the advantage of knowing him for a great number of years—ever since I was a boy—and I need hardly say how deeply I deplore the fact that he can be no more in our midst. But his name will be cherished and honoured throughout the country."

[8]It is not necessary to dwell more lengthily on this salient aspect of Leighton. During his lifetime it was public property, the great name he has left is evidence sufficient to coming generations.

Secondly, as portrayed chiefly by his human qualities, there was the aspect of Leighton as his family and his friends knew him; the beloved Leighton, the delightful companion, the charming personality, the being whose brilliant vitality brought a mental stimulus into all intercourse with him. The Leighton qui savait vivre perhaps better than did ever any other conspicuous, overworked servant of the public; an active, positive influence, radiating strength and sunshine by his presence; and playing the game—whatever game it was—better than even the experts in special games. In that which perhaps he played best, lay his remarkable social power. Leighton had a deep-rooted and ingenuous sincerity of nature, and never for a moment lost his self-centre; yet he had the rare gift of unlocking the side most worthy to be unlocked in the nature of his companion of the moment. He had the power of evolving out of most people he met something that was real and of interest. Never giving himself away, he yet managed to meet other individualities on any ground that existed which could by any possibility be made a mutual ground. Though generosity itself in believing the best of every one, and at times entrapped by the wily, anything like flattery was a vice in his eyes. He neither gave himself away, nor induced others to give themselves away while in his company, and would always abstain from obtruding his opinions, modestly withholding judgment where he saw neither a duty nor a distinct reason to pronounce.

Perhaps the strongest mark of Leighton's true distinction lay in the fact that, notwithstanding his reserve on all matters of deep feeling, notwithstanding his love of form in the living of life as in the creating of art, notwithstanding the [9]perpetually shifting and urgent claims which, as a public man and a prominent social entity, were being continually forced upon him, the inner entity, the real Leighton, remained to the end a child of nature. No need was there for him to gauge the proportionate merit of the various conflicting influences that played on his complicated life; his own instinctive preferences clenched the matter indubitably, asserting that the noblest grace and the finest taste lay in the spontaneous and the natural. When Watts wished it recorded that Leighton's nature was the most beautiful he had ever known, he referred, I think, more specially to that lovable, kind-hearted ingenuousness and noble simplicity which were its deepest roots, notwithstanding a life of conflicts, ambitions, and unparalleled success. There are among those who most honour and love Leighton's memory, and who felt most keenly his loss, poor and unsuccessful artists and students, of whom the world has never heard, but to whom the great President gave of his very best in advice and sympathy.[4] He never posed, though he was an adept in catching the atmosphere of a situation, [10]however new and foreign to his usual beat such a situation might be. Scrupulous in his attitude of reverence towards his vocation as an artist, ever most scrupulous to render unto Cæsar the things that are Cæsar's, the inner core of the nature remained simple and unstained by worldliness.

Then there was the third aspect of Leighton, the Leighton at times half-hidden from himself; the yearning, unsatisfied spirit, which, though subject at times to great elevations of delight, at others was also the victim of profound depressions and a sense of loneliness—a state of being born out of that strange, only half-explained region whence proceed all intuitive faculties. Such states are referred to occasionally in his letters to his mother, and we find their influence recorded at intervals in his art. In 1849, on a sketch of Giotto when a boy, are written in the corner the words "Sehnsucht"; in 1865, there is the David, "Oh, that I had wings like a dove; for then would I fly away and be at rest"; in 1894, the "Spirit of the Summit"—these are all alike expressions of the home-sickness that yearned for an abiding resting-place not found in the conditions of this world. "Oh, what a disappointing world it is!" were words he uttered shortly before his death. In 1894, when at Bayreuth, a friend was congratulating him on his ever fortunate star having even there easily overcome the difficulties of the crowd. Leighton, passing over the immediate question, answered with a striking serious sadness, "I have not ever got what I most wanted in this world."

No mind was ever more explicit to itself in its mental working, than was his with regard to matters which the intellect can investigate and solve. His judgment could never be warped by reason of an insufficient brain apparatus with which to judge himself and others impartially. But Leighton was a great man, beyond being the one who owned "a magnificent intellectual capacity." The qualities he possessed, which made [11]him a prominent entity who influenced the interests of the world at large, secured for him a footing on that higher level where human nature breathes a finer, more rarefied atmosphere than that in which the intellect alone disports itself; a level from which can be viewed the just proportion existing between the truly great and the truly little. Selfishness disappears in a nature such as Leighton possessed, when that level is reached. The necessity for self-sacrifice forces itself so peremptorily, that there is no struggle to be gone through in exercising it. For instance—notwithstanding the absorbing nature of his occupations and the intense devotion he felt towards his vocation as an artist, when it was a question of the country needing a reserve force for her army to draw on in case of war—a need which is at this present moment insisted on by Lord Roberts with such zealous earnestness—Leighton at once seized the importance of the question, and, at whatever sacrifice to his own more personal interests, enlisted as a volunteer, and mastered the art and duties of soldiering so completely that many officers in the regular army envied his knowledge and efficiency.

The following is an appreciation by an old comrade in the Artists' Volunteer Corps:—

"The names of those who first enrolled themselves to form the Artists' Volunteer Corps in 1860 is a record of considerable interest in itself, and calls back many reminiscences connected with art. Leighton joined May 10, 1860, and was in a few days given his commission as ensign.

"Probably the very character of the first recruits tended to prevent that expansion and accession of numbers without which no military body can flourish. Lord Bury, the first commandant, became the Colonel of the Civil Service Rifles; and whatever attention may have been given to firing and detailed training, the early appearances of the 'Artists' in [12]public at reviews was, as a rule, as a company or two attached to the Civil Service Rifle Corps.

"Events, however, brought a change in the command, and Leighton having, not without hesitation, accepted it, set himself at once to introduce reforms. The Captains, he announced, were to be responsible each for the command and drill of his company. He, to carry out before promotion as Major Commanding a duty which the previous laxity had never required of him, learned the company drill by heart and went through the whole complicated system then existing, on a single evening under trying circumstances in very insufficient space. Reorganisation did not rapidly fill the ranks, and there was much hard work to be done before the Artists' Corps appeared as a completed eight-company battalion, and took its place among the best of the Volunteer Corps of the Metropolis. The personality of the Commander did very much to achieve this result, and Leighton became Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant in 1876.

"Next to his duty to his Art and to the Royal Academy, as he was ever careful to say, he esteemed his duty in the Corps. Busy man, with his time mapped out more than most, he was always accessible and ready to give the necessary time to those who had access to him on the Corps business. He never appeared on parade without previous study of the drill to be gone through, while his tact, energy, and personal charm were brought out and used at those social meetings with officers and with men which do so much to build up the tone of a volunteer body.

"Of camps and duties in the tented field he took his part cheerfully. He shared the hardship of the early experience of the detachment at the Dartmoor Manœuvres, where, camping on the barren hills above the lower level of the mist, the extemporised commissariat followed with difficulty, and the officers consoled themselves for the roughness of their [13]fare by the consumption of marmalade, which happened to be supplied in bulk, and had to clean their knives in the sand to make some show for the entertainment of the Brigadier at such dinner as could be had.

"Regarding volunteering so earnestly as he did, the reports of the Inspecting Officers would appear of great importance in Leighton's eyes. On one occasion paragraphs had appeared in the papers about the Corps which probably gave some umbrage to the authorities. The Inspecting Officer kept the battalion an unconscionable time at drill, changed the command, fell out the Staff Sergeants, yet all went well. At length, with Leighton again in command, and a word imperfectly heard, the square walked outwards in four directions. The confusion was put to rights, and the well-prepared speech from the Inspecting Officer as to the importance of battalion drills, &c., followed. It was quite a pleasure to point out to the distressed Leighton that the whole was manifestly a 'put up thing.'

"The answer he received on another occasion admitted of no misinterpretation. Riding with the Officer after the inspection, and anxious to know whether in his opinion he was really doing any good work by his volunteering, Leighton asked whether the Officer would be willing to take the battalion he had just inspected under fire, and received the laconic reply, 'Yes, sir, hell fire.'

"On Leighton's election as President of the Academy, his twenty-five years active service in the Corps ceased in 1883. All the time that the history of the volunteering of the nineteenth century is known, his name will be associated with the Artists' Corps to the honour of both."

Mr. Hamo Thornycroft, R.A., also adds his tribute in the following lines:—

"I should think that few Commanding Officers of Volunteer Regiments could surpass Colonel Leighton in efficiency. [14]His wonderful knowledge of infantry drill, and the decision with which he gave the word of command, made it very easy for the men in the ranks to obey him; and the quickness of eye with which he detected an error in any movement frequently saved confusion in the ranks on a field day. The Artists' Corps soon became one of the smartest in London. I well remember how efficiently he commanded the Volunteer Battalion in the Army Manœuvres on Dartmoor in 1876, when for a fortnight of almost continuous rain on that wild moorland he kept us all happy and full of respect for him by his fine soldierly example. His thoroughness and kindness were constant. After a soaking wet night he would come down the line of tents in the early morning distributing some unheard-of luxury, such as a couple of new-laid eggs to each man, which he had managed to have sent from some outlying village."

Besides the obvious results of a complex and astonishingly comprehensive nature, there were also phases in Leighton's life which were the outcome on that side of his being half hidden to himself.

Most of us have dual natures, not only in the sense that good and bad reside within us simultaneously, but we have also a less definable duality of nature; nature's original creature being one thing, and the creature developed by the conditions it meets with in its journey through life, another. Each acts and reacts on the other. We meet the conditions forced upon us in life from the point of our own individualities. On the other hand, the original creature gets twisted by circumstances and the influence of other personalities, and becomes partially altered into a different person. This backwards and forwards swaying of the influence of nature and circumstances helps to make life the intricate business it is. In the case of highly gifted human beings there seem to be further complications, arising chiefly, perhaps, from the fact that these form so small [15]a minority. Very subtle and undefinable is the effect of such gifts on the character and nature of those possessing them, for nature herself maintains a kind of secrecy and endows her favoured ones with but a half consciousness in respect of them. She gives to the artist and to the poet the something, unshared with the ordinary mortal, which controls the inner core of his being, and which is another quantity to be allowed for in his contact with his fellows. It initiates his most passionate, peremptory conditions of temperament, yet it remains partially veiled to himself, in so far that he cannot explain it, nor give it its right place, any more than the lover can explain the glamour which is spread over life by an overpowering first love. When Plato classes the souls of the philosopher, the artist, the musician, and the lover together[5] as having been born to see most of truth, he recognises the same inspired instinctive quality in the artist as in the lover. In the artist is linked, as part of its separateness from the rest of the community, the inseparable shyness of the lover. Anything is better than to expose the sacred, indescribable treasure to the indifferent stare of the uninitiated. We find every sort of ruse adopted by lovers and artists to avoid being forced into explicitness on so tender, so intimate a passion; so convincing to its possessor, so impossible of full explanation to those who possess it not. The necessity to give it a clear outline is only forced when a danger arises of the lover being robbed of his mistress, the artist of his vocation; then the will, propelled by [16]the all-conquering love, asserts itself, and difficulties have to succumb before it.

Such was the result of opposition in Leighton's case. From early childhood he was known to care for nothing so much as for drawing, and his talent attracted notice and pleased his family, every encouragement being given him by his parents in his studies. It was only when, as a boy of twelve, he viewed art as the serious work of his future life, and when this view was met by the authorities as one not to be encouraged, that the strong passion of his nature asserted its rights. Clearly in opposition are planted the firmest roots of those inevitable developments which make the great of the world great. In Leighton was nurtured that sense of responsibility towards his vocation, so salient a characteristic throughout his career, partly by his father's attitude towards the worship of his nature for beauty and for her exponent art. To prove that his self-chosen labour was no mere play work, no mere avoiding the hard work of life and the duller paths of service generally recognised only as of serious use to mankind, for a game which was a mere pleasure, was a strong additional incentive to Leighton's own high aspirations, inspiring him yet more to treat the development of his gifts as a moral responsibility. He considered it almost in the light of a debt owing to those to whom he was attached by strong family affection, that he should prove good his cause. Though he fought and overcame, having once won his point, he did his utmost to satisfy his father's ambition for him, and to be "eminent."

On August 5, 1879, he wrote to Mrs. Mark Pattison, who was compiling notes for an article on his life: "My father, of his own impulse, sat down to write a few jottings, which I cannot resist sending you, because I was touched at the thought in this kind old man of eighty. He, by the way, is a fine scholar, and was, at his best, a man of exceptional [17]intellectual powers. My desire to be an artist dates as far back as my memory, and was wholly spontaneous, or rather unprompted. My parents surrounded me with every facility to learn drawing, but, as I have told you, strongly discountenanced the idea of my being an artist unless I could be eminent in art."

| From Miniatures, by permission of Mr. H.S. Mendelssohn | |

Still—though to excel was Leighton's aim, in order to satisfy his father's and also his own ambition—within the hidden recesses of that aim lay the reverent, more single-hearted worship for his mistress Art—seldom unveiled, it would seem, when with his father, to whose purely intellectual and philosophical attitude of mind it would not have appealed. Those alone possessed the key to that inner sanctuary who did not need the key; who wanted no introduction, and were not merely sympathisers, but native inhabitants. There is a freemasonry between the inmates of these places remote from the world's usual habitations, and these, naturally, have a horror of vaunting the possession of a sacred ground to the outsider, the uninitiated. Many of Leighton's most intimate acquaintances gathered no clue, through their knowledge of him, of the existence of the secluded spot. Dr. Leighton's influence, however, non-artistic as was his nature, stimulated his son's natural mental elasticity, encouraging a comprehensive and unprejudiced view of life and people, a view which marked Leighton's undertakings with a stamp of nobility and distinction throughout his career. Yet further—the intellectual training he received in youth probably enlarged, in some respects, the areas of the sacred sanctuary itself, enabling Leighton, when he was the servant of the public and possessing wide influence and patronage, not only to exercise power with the qualities which spring from a high intellectual development, but to mellow with wisdom the guidance of the yet higher sympathies of the heart, when helping those staggering along the road which he himself had travelled over with [18]such success. To many, however, especially to those possessing the artistic temperament, it must always remain, to say the least, a questionable advantage to a student of art that his intellectual faculties should be forced forward at the expense of the development of his more emotional and ingenuous instincts, at the age when sensitiveness to receive impressions is keenest, and when such impressions have the most lasting power in moulding the future tendencies of his nature. Certainly the effects of a development of critical and analytical faculties is apt to prove a damper to those ecstasies of enthusiasm which inspire the most convincing conceptions in art. When first starting and facing seriously his independent career alone, Leighton writes to his mother: "I wish that I had a mind, simple and unconscious as a child." Again, writing to his elder sister from Algiers in 1857, after describing the delightful impression produced by a first visit to an Eastern country, he adds: "And yet what I have said of my feelings, though literally true, does not give you an exactly true notion, for together with, and as it were behind, so much pleasurable emotion, there is always that other strange second man in me, calm, observant, critical, unmoved, blasé—odious! He is a shadow that walks with me, a sort of nineteenth-century canker of doubt and dissection; it's very, very seldom that I forget his loathsome presence. What cheering things I find to say!"

Allied to the third, more intimate aspect of his nature were phases in Leighton's feelings when heart would seem to conquer head. He would at times indulge in what might almost be designated as a self-imposed blindness, when he would allow of no criticism by himself or others of the cause or person in question. An enthusiastic, unselfish devotion, a sense of chivalry or pity, would override his normally clear-sighted, intellectual acumen. Having set his belief and admiration [19]to one tune, faithful loyalty—and maybe a certain amount of obstinacy—would bind him fast in an adherence to the same.

Belonging also to the intuitive, more emotional side of his nature, was the curiously strong influence places exercised over him, certain localities affecting him and exciting his sympathies with a strong power.

In 1857 he wrote to his elder sister: "If I am as faithful to my wife as I am to the places I love, I shall do very well!"

In order to seize fully Leighton's complete individuality, an understanding of Italy, his "second home," is perhaps necessary—a conception of the nature of the unsophisticated Italian life which fascinated him so greatly when as yet no invasion had been made of cosmopolitan, so-called civilisation. As a magnet, Italy drew Leighton to her.[6] Under the influence of her radiant beauty, breathing such a life of charm and colour beneath sunlit skies, he felt the sources of happiness in his own nature expand and his powers ripen. In the fertility of her soil, the vitality of her people, the superb quality of her art—fine and gracious in its perfection, and distributed [20]generously throughout the length and breadth of her land—he experienced influences which intensified his emotions and vivified his imagination. The child-like charm of her people, so spontaneously happy, enjoying the ease and assurance of nature's own aristocracy, because enjoying nature's generous gifts with unabashed fulness of sensation, in whom are non-existent those sensibilities which create self-consciousness, restraint, and an absence of self-confidence, aroused in Leighton an interest deeper than mere pleasure. It was to him like the joy of a yearning satisfied, as of those who, having had their lot cast for years with aliens and foreigners, find themselves again with their own kith and kin, surrounded by the native atmosphere which had lent such enchantment to childhood. Again and again he returned to Italy to be made happy, to be revived, to be strengthened by her. Her influence became kneaded into his very being, not only nourishing his sense of beauty and rendering more complete the artist nature within him, but touching the sources from which his artist temperament sprang, inspiring his very personality and changing it into one which was certainly not typically English. His rapid utterance, his picturesque gesture, his very appearance, were not emphatically English.[7]

Certain Englishmen who knew Leighton but slightly felt out of sympathy with him for this reason, experiencing a difficulty in recognising him as one of themselves. It was, however, only on the surface that a difference existed. Once intimate with Leighton, he was ever found to be au fond English of the English. After the age of thirty it was in England Leighton fought the serious battle of life—Italy was but the playground, though a playground of such fascination [21]to him that the glamour of it was spread over the working hours no less than over the holidays. In these days we have to go into the smaller towns and villages to discover the typical Italian characteristics; but when Leighton, as a child, was taken from the gloom of Bloomsbury to this, to him a magic world,—syndicates, building-companies, tramways, and modern things generally, had not as yet invaded either Rome or Florence. When grown up and master of his own actions, he wandered into unsophisticated haunts—villages and towns off the beaten tracks, where with abnormal facility he learned the distinctive pâtois of every district, listening with delight to local folk-songs, and watching the peasants and the aborigines of the soil. In early sketch-books we find records of visits to Albano, Tivoli, Cervaro, Subiaco, San Giuminiano, and to even smaller and less known villages in Tuscany and Veneziano, where he enjoyed the unalloyed flavour of Italy and her people. Those who pay only flying visits to the country after they are grown up would find a difficulty perhaps in realising what Italy was to Leighton; but any one visiting for a few weeks even such a well-known place as Albano, without other preoccupation than to watch the natives and wander in the beautiful scenery to the sound of the many flowing fountains, could still catch something of the true national spirit which fascinated him so greatly. The typical Britisher might regard the ways of these natives of the Provincia di Roma as irrational, idle, semi-savage. Doubtless the streets and piazzas abound in noisy inhabitants, gesticulating with wild dramatic fervour, who appear to have otherwise little to do in life but to loiter and "look on"; sociable groups of women sit round the doorways knitting; but it is the talk, accompanied by excited action, which is engrossing them. Charmingly pretty children are playing everywhere—idle, troublesome, but so happy! To the [22]accompanying sound of running waters,—night and day,—cries, yells, and songs ring out through the ancient little town.[8] High up on the side of the mountains it overlooks the Roman Campagna, the tragic strangeness of those land-waves rolling away, flattened and stretched out, for miles and miles, under the dome of light and shadowing cloud, a network of bright gleams and violet lakelets, to the far-off brilliant shine on the sea limit.[9] This noise, dramatic action, gesticulation, all ending apparently in nothing in particular, but filling the little town with such amazing vitality—what is it all about? The typical Englishman does not know—does not care to know, despising the whole thing as beneath his notice. But Leighton knew well what it meant. From experiences in his own nature he realised that it was but an innocent outlet, through voice and gesture, of an excitement resulting from an imperative dramatic instinct, a vital force in the emotional nature of the Italian. He recognised the necessity for such an outlet in such temperaments through his sympathy with the glad exuberance of physical vitality enjoyed in this sunlit land; anti-puritan though it may be, this exuberance is none the less pure and innocent.

The holy Saint Francis in his ecstasies of spiritual illumination would, it is said, break out into song from the natural impulse to find an outlet and to throw off the excess of excitement, that thrilled through his being.[10]

[23]Leighton knew that to suppress the vitality which needs such an outlet was to minimise the forces necessary for life's best work. He himself, in the working of his mind, was possessed of a magnificent facility—a facility which left the strength of his emotions fresh and free, to enjoy the ecstasies of admiration and delight which the choice gifts of nature and art had given him; but there are many among modern men and women, taught by much reading, who overweight their physical vitality in the effort to develop intellect and to forward self-interest, till all simple physical enjoyment is lost, and the natural man becomes repressed into a mental machine incapable of any spontaneous emotions of joy, and blunt to the fine aroma of life's keen and pure pleasures—

To Leighton the simple joyous child of nature, in the form of the unsophisticated Italian, was a preferable being. To the end of his life he retained much of the child in his own nature, and had ever an inborn sympathy with the love for children so evident everywhere in unspoilt Italy; for the gracious caressing of them by the poorest of the poor—old men in the veriest tatters and rags showing a complete and beautiful submission to the dominating charms of babyhood.

The memory of the hideous, gruesome stories of baby-farming in England strikes indeed a contrast with the scenes [24]that abound at every turn in any old, dirty, picturesque Italian village, and assuredly settles the question, Is our English development of civilisation an unalloyed benefit?

As a contrast to the definite, explicit German development of his intellectual machinery, Leighton had special sympathy with the emotional spontaneity of the Italian race; also as a contrast to the selective and finely poised conclusions to be worked out in theories of composition learnt from his beloved master Steinle, arose a special admiration for the casual, unpremeditated, inevitable grace and charm in the manners and gestures of this southern people. What laboured theories so often failed to achieve, nature here was always doing in her most careless moods.

In considering the intimate aspect of Leighton's nature, and the interweaving of the original fabric with the forces developed by the circumstances he encountered, the influence of Italy must assuredly be given a very distinct prominence. From her and her people he acquired courage in the exercise of his intuitive preferences, also a development of that rapid and direct insight so inborn in her children. Like the lizards that dart with such lightning speed across her sun-scorched walls and over the gnarled bark of the weird olive tree, the perceptions of the typical Italian are swift, and fly straight to the mark. In the Italian, however, this vividness of perception is mostly expended in ejaculation and dramatic gesture, which,—subsiding,—leaves a state of indolence and nonchalance, untroubled by any mental exertion. In Leighton the rapidity with which his perceptions seized the core of truth was backed by an intellectual activity of extraordinary power, by which he worked his intuitive sensibilities into the interests which guided the solid aims of his life.

Probably no Englishman ever approached the Greek of the Periclean period so nearly as did Leighton, for the reason that he possessed that combination of intellectual and emotional [25]power in a like rare degree. The human beings who achieve most as active workers in the world, are doubtless those in whom can be traced a capacity for making apparently incompatible forces pull together towards a desired end. Leighton succeeded in allying two distinct developments in his nature; and by, so to say, putting these into double harness and driving them together, acquired an advantage which few other artists, if any, have possessed since the time of the Greeks.

But, being essentially English as well as Greek-like, Leighton pushed this combination of powers to a moral issue. He held as his creed of creeds that the mission of Art was to act as a lever in the uplifting of the human race, not by going beyond her own domain, but by directing the sense of beauty with which her true priesthood must ever be endowed, in order to eliminate from man his more brutal tendencies, to refine and perfect his insight into nature, and to develop his delight in her perfection. He held that, the stronger the emotional force in an artist, the stronger the sense of responsibility should be; the more he should seek to express it in a manner which would elevate rather than deprave. In his picture of "Cymon and Iphigenia," Leighton expressed the main dogma of his belief. In sentences towards the end of his second address to the Royal Academy students in the year 1881, he eloquently describes the complex and deep nature of those æsthetic emotions whence spring the Arts:—

"It is not, it cannot be, the foremost duty of Art to seek to embody that which it cannot adequately present, and to enter into a competition in which it is doomed to inevitable defeat.

"On the other hand, there is a field in which she has no rival. We have within us the faculty for a range of emotions of vast compass, of exquisite subtlety, and of irresistible force, to which Art and Art alone amongst human forms of expression has a key; these then, and no others, are the chords which it is her appointed duty to strike; and Form, Colour, [26]and the contrasts of Light and Shade are the agents through which it is given to her to set them in motion. Her duty is, therefore, to awaken those sensations directly emotional and indirectly intellectual, which can be communicated only through the sense of sight, to the delight of which she has primarily to minister. And the dignity of these sensations lies in this, that they are inseparably connected by association of ideas, with a range of perceptions and feelings of infinite variety and scope. They come fraught with dim complex memories of all the ever-shifting spectacle of inanimate creation, and of the more deeply stirring phenomena of life; of the storm and the lull, the splendour and the darkness of the outer world; of the storm and the lull, the splendour and the darkness of the changeful and transitory lives of men. Nay, so closely overlaid is the simple æsthetic sensation with elements of ethic or intellectual emotion by these constant and manifold accretions of associated ideas, that it is difficult to conceive of it independently of this precious overgrowth.... The most sensitively religious mind may indeed rest satisfied in the consciousness that it is not on the wings of abstract thought alone that we rise to the highest moods of contemplation, or to the most chastened moral temper; and assuredly Arts which have for their chief task to reveal the inmost springs of Beauty in the created world, to display all the pomp of the teeming earth, and all the pageant of those heavens of which we are told that they declare the Glory of God, are not the least eloquent witnesses to the might and to the majesty of the mysterious and eternal Fountain of all good things."

Not only could no attempt be approximately made at giving a real and vivid picture of Leighton's remarkable personality were not the three aspects of his nature taken into account, but also if the influences which affected him strongly during those years when his genius and character were being [27]developed were not also considered. His conscious nature and feelings, during the first thirty years of his life, can be best traced in his letters, notably in those to his mother. It is easy to recognise, in reading his mother's letters to him, from whom he inherits the warm tender generosity which made his nature so lovable.

When at Frankfort, in 1845, he first became acquainted with the most "indelible" influence of his life in that inner sanctuary in which he had hitherto been a lonely inmate. Seven years later, in the Diary he calls "Pebbles," written for his mother, when, fully fledged, he leaves the nest to battle alone on the field of life, he pays a tribute of unqualified affection and gratitude to his master, Steinle, who first unlocked the door to Leighton's full consciousness of the depth of his devotion for his calling (see pp. 61 and 62).

In 1879, the year after Leighton was elected President of the Royal Academy, in the same letter to Mrs. Mark Pattison already quoted from, he writes, respecting the influences which affected his art development: "For bad by Florentine Academy, for good, far beyond all others, by Steinle, a noble-minded, single-hearted artist, s'il en fut. Technically, I learnt (later) much from Robert Fleury, but being very receptive and prone to admire, I have learnt, and still do, from innumerable artists, big and small. Steinle's is, however, the indelible seal. The thoroughness of all the great old masters is so pervading a quality that I look upon them all as forming one aristocracy."

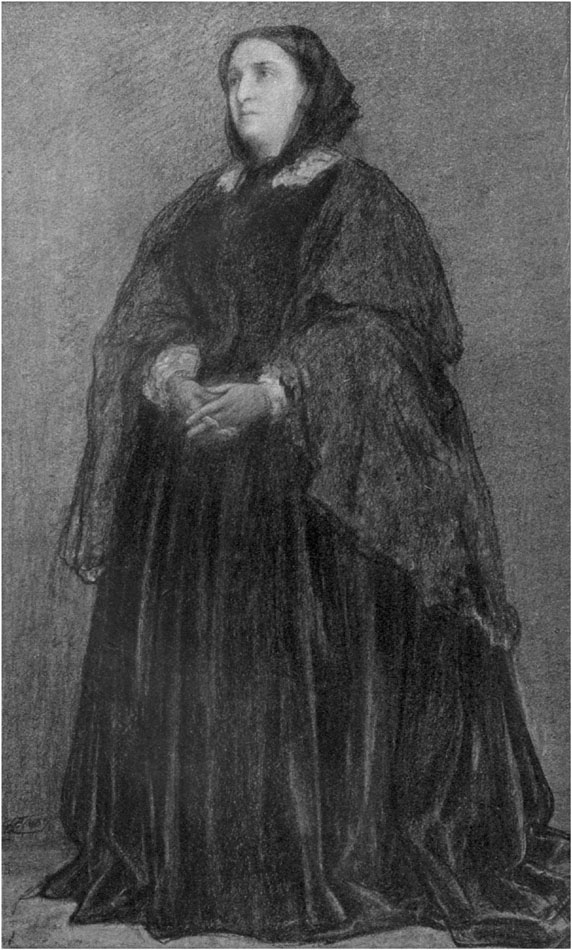

During the first year when he settled in Rome, in the beginning of 1853, he made the acquaintance of Mr. and Mrs. Sartoris. Leighton's friendship with Mrs. Sartoris (Adelaide Kemble), many years his senior, and one who had ever viewed her art as a singer from the purest and highest aspect, became a strong and elevating influence in his life. Professor [28]Giovanni Costa (the "Nino" of the letters), one of Leighton's most intimate friends from the year 1853 to the end in 1896, wrote of Mrs. Sartoris, referring to the early days in Rome from 1853 to 1856:[11] "The greatest influence on the life of Frederic Leighton was exerted by Mr. and Mrs. Sartoris (Miss Adelaide Kemble), who had the mind of a great artist. Mr. Sartoris was one of the greatest critics of art, and Mrs. Sartoris had a most elevated and serene nature."

This great friendship with Mr. and Mrs. Sartoris brought with it many others, notably those of Robert Browning and of Mr. Henry Greville. Some years later, Leighton writes of Mr. Henry Greville, in a letter to his pupil and friend, Mr. John Walker: "He is indeed one of the kindest and best men possible, I look on him myself as a second father"; and Henry Greville in a letter to Leighton writes: "I wish you were my son, Fay"—Fay being the name given to Leighton by his inner circle of intimates, and certainly a stroke of genius in the one who invented it. Writing from Frankfort to his mother, where he returned to show his works to Steinle after his family had finally migrated to Bath and he to Rome, he says: "I have had such a letter from Henry (Henry Greville); there never was anything like the tenderness of it. You would have been just enchanted."

The friendship with Mrs. Sartoris only ended with her death in 1879, the year after Leighton was elected President of the Royal Academy. Being then close upon fifty, deeply sensible of the grave responsibilities involved by his new position, Leighton entered on a fresh phase in his career. As president of the centre of national living art, this phase involved a serious view being taken of the interests of art such as could be encouraged by a public body. Also as one who had been helped and encouraged by personal friendship and influence to work out the best in him, with his ever eager [29]and generous nature he felt anxious to hand on the help he had received by devoting a like sympathy to the individual interests of other workers. His field of action had become enlarged, and he rose with consummate ability to the fulfilment of the duties this larger area entailed on him. Not only by his biennial addresses to the students of the Royal Academy, but by the speeches delivered spontaneously at the councils and elsewhere, when no preparation would have been possible, his fame as an orator was established. Many there are who have heard the impromptu speeches he made, who can vouch, as do Mr. Briton Rivière and Mr. Hamo Thornycroft, that these were just as fine in language and excellent in the concise form in which the words were made to convey the intended meaning, as those which Leighton had carefully prepared beforehand, and possessed, moreover, the charm of an unlaboured effort.

The seventeen years, during which Leighton was President of the Royal Academy, and prominent in every direction as the leader of the art of his country, were not without saddening influences. His duties necessitated contact with many varieties of human nature, some far from sympathetic to him. The contrast between his own disinterested reverence for beauty, moral and physical, with the indifference displayed by many of his brother artists towards his own high aims and aspirations, forced itself more and more on Leighton as the optimistic fervour and enthusiasm of youth waned with years and failing health. He had to face the depressing fact that selfish motives are the ruling factors with most men, even with those who ostensibly follow the calling of beauty. Much of the joyousness of his spirit was lessened accordingly, though his "sweet reasonableness," to quote Watts' truly suggestive words, never deserted him. This prevented any bitterness or resentment from finding permanent location in his nature. Another source of distress arose from the fact that his great [30]position aroused the jealousy of the envious. However exceptional his tact, however truly heartfelt his consideration for others, no virtues could stand against the vice of being so pre-eminently successful in the eyes of the envious, whose vanity alone placed them in their own estimation on a level with the great.

Nothing perhaps excites so rampant a jealousy in unappreciative and envious natures, as does the unexplainable charm of a delightful personality. It aggravates the dull and envious beyond measure to see a being thus endowed galloping over the ground in all directions with ease, there being in their eyes no sufficient explanation for the pace. Such success is viewed by the envious as a kind of trick, some witchery of fascination, which deludes the world into bestowing unmerited advantages on the conjuror. Those, on the contrary, who can appreciate a transcendent and delightful personality, recognise it as the convincing grace of the power of uncommon gifts flashing their radiance into the intercourse of every-day life, modestly ignored as conscious possessions but inevitably sparkling out in any human intercourse, and from a social point of view making the greatest among us the servants of all.

Jealousy fights with hidden weapons. What man or woman ever acknowledged being jealous? The passion is disguised. Hence the hideous sins that follow in its wake: ingratitude, treachery, calumnies, are called into the service to blacken the offending object. Bacon says of envy: "It is also the vilest affection, and the most depraved; for which cause it is the proper attribute of the devil, who is called the envious man, that soweth tares amongst the wheat by night, as it always cometh to pass that envy worketh subtilly, and in the dark; and to the prejudice of good things, such as is the wheat."

Leighton suffered from the jealousy of the envious, though in most cases the open expression of it was smothered during [31]his life by reason of his power and position. Besides being tender-hearted and easily hurt at any feeling of hostility shown against him, he cordially hated any phase of the ugly.

In the spring of 1895 Leighton said to a friend: "My one constant prayer is that I should not live beyond seventy." His great dread was to be a burden to any one—to cease to be useful to all. His wish was more than fulfilled. He passed onward five years before the allotted three score and ten.

Many there were who felt with Watts that life was indeed darkened; "a great light was extinguished," a beloved friend was no longer amongst them to help, encourage, and brighten the days. To a wide social circle, a personality, rare in its charm and endowments, differing from all others, had passed off the stage. It was as if, amid the sober brown and grey plumage of our quiet-coloured English birds, through the mists and fogs of our northern clime, there had sped across the page of our nineteenth century history the flight of some brilliant-hued flamingo, emitting flashes of light and colour on his way.

To the wide public a power and a control, noble and distinguished in its quality, had ceased to rule over the art interests of the country. Last, but not least, to his "brothers and sisters," as Leighton called all earnest students and artists, it was as if a strong support, a centre of impelling force, an inspiration towards the best and highest in art, had been suddenly swept away.

On the day of his funeral, a friend, whose husband had known him from the commencement to the end of the brilliant career, wrote the following notes:—[12]

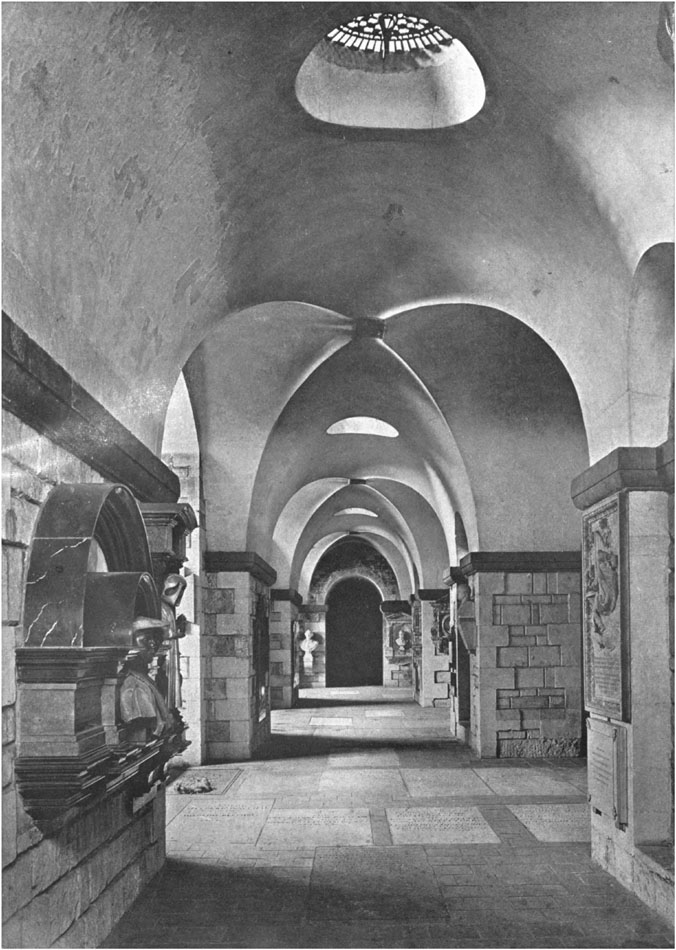

"Lord Leighton's funeral to-day was as brilliant as his life, and we came home from the majestic ceremony at St. Paul's Cathedral feeling that his kind and gracious spirit would have rejoiced—for all he loved and honoured in life were there [32]mourning for the loss of their gifted and genial friend. As the procession moved slowly into the Cathedral the crimson and golden pall was Venetian in its brilliancy, and the long branch of palm spoke touchingly of pain over and the conquest won. Music, the sister Art he so devoutly worshipped, lifted up her voice in pathetic accents to the dome of the vast Cathedral, striving to re-echo the solemnity and grief around.

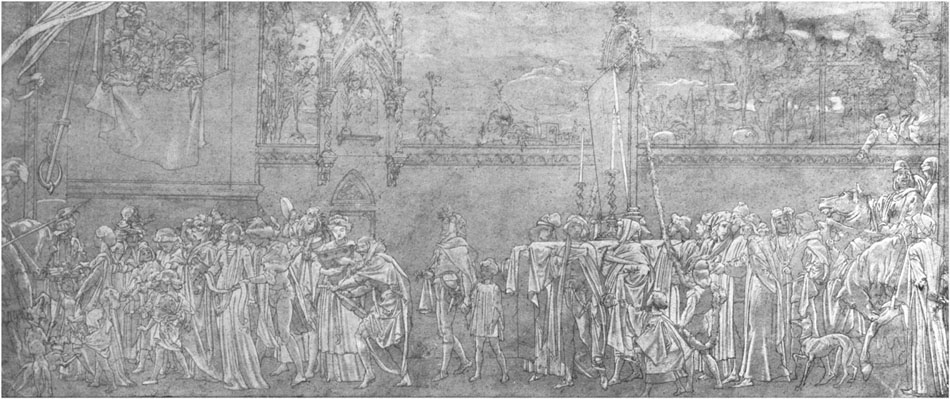

"Dear gracious Leighton, how vividly my husband recalled his earliest impressions of him, the handsome young artist at Rome. Visions arise in the mind of joyous days in his second home there, the cultured and hospitable house of Adelaide Sartoris, which formed the happy background of Leighton's life. He remembered the departure of his picture 'The Triumph of Cimabue,' sent with diffidence, and so, proportionate was the joy when news came of its success, and that the Queen had bought it. It was the month of May. Rome was at its loveliest, and Leighton's friends and brother artists gave him a festal dinner to celebrate his honours. On receiving the news, Leighton's first act was to fly to three less successful artists and buy a picture from each of them (George Mason, then still unknown, was one), and so Leighton reflected his own happiness at once on others. To-day as we viewed the distinguished (in the best sense of the term) mourners, it seemed an epitome of all his social and artistic life. He never forgot an old friend, and not one was absent to-day. The men around his coffin all looked heartily sad. It was only when those peaceful words came, 'We give Thee hearty thanks, for that it hath pleased Thee to deliver this our brother out of the miseries of this sinful world,' that we remembered the agony of his last three days on earth, and we could be glad for our dear friend that it was past. We could give hearty thanks, but it was for him and him alone, for we turn with heavy hearts to our homes, feeling [33]that with Frederic Leighton ever so much kindness, love, and colour has gone out of the world."

CRYPT UNDER ST. PAUL'S CATHEDRAL, WHERE BARRY, SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS, TURNER, AND LORD LEIGHTON WERE BURIED

From a photo, by permission of Messrs. S.B. Bolas & Co.ToList

Attached to the wreath which lay on his coffin were the lines written by our Queen:—

In Leighton's own letters, more than is possible in any other written words, will be traced those qualities of character and feeling which guided the rare gifts nature had bestowed. These, used with unstinting generosity for the benefit of others, established for our national art a position, cosmopolitan in its influence, never previously attained by English painting and sculpture, and of which it may be fairly hoped, future generations, no less than the present, may reap the benefit.

[1] George Eliot—"Romola."

[2] Lord Loch's cousin, Colonel Sutherland Orr, married Leighton's elder sister in the year 1857.

[3] Quoted in G.F. Watts' "Reminiscences."

[4] An incident, one out of many that tell of Leighton's hearty, eager helpfulness, happened on one of the evenings at the Academy, after the prizes had been given away. A student was passing through the first room, on his way to the entrance. He looked the picture of dejection and disappointed wretchedness, poorly and shabbily dressed, and slinking away as if he wished to pass out of the place unnoticed. Millais and Leighton, walking arm in arm, came along, pictures of prosperity. Leighton caught sight of the poor, downcast student. Leaving Millais, he darted across the vestibule to him, and, taking the student's arm, drew him back into the first room, and made him sit down on the ottoman beside him. Putting his arm on the top of the ottoman, and resting his head on his hand, Leighton began to talk as he alone could talk; pouring forth volumes of earnest, rapid utterances, as if everything in the world depended on his words conveying what he wanted them to convey. He went on and on. The shabby figure gradually seemed to pull itself together, and, at last, when they both rose, he seemed to have become another creature. Leighton shook hands with him, and the youth went on his way rejoicing. It is certain that if other help than advice were needed, it was given. But it was the extraordinary zest and vitality which Leighton put into his help which made it unlike any other. He fought every one's cause even better than others fight their own.

[5] In Plato's "Phædrus," Socrates says: "The soul, which has seen most of trouble, shall come to the birth as a philosopher, or artist, or musician, or lover; that which has seen truth in the second degree, shall be a righteous king, or warrior, or lord; the soul which is of the third class, shall be a politician, or economist, or trader; the fourth, shall be a lover of gymnastic toils, or a physician; the fifth, a prophet, or hierophant; to the sixth, a poet or imitator will be 'appropriate'; to the seventh, the life of an artisan, or husbandman; to the eighth, that of a sophist, or demagogue; to the ninth, that of a tyrant; all these are states of probation, in which he who lives righteously, improves, and he who lives unrighteously, deteriorates his lot."

[6] He wrote to his sister in 1857 from Algiers: "I shall spend my next winter in my dear, dear old Rome, to which I am attached beyond measure; indeed, Italy altogether has a hold on my heart that no other country ever can have (except, of course, my own), and although, as I just now said, I was most delighted with Africa, and have not a moment to look back to that was not agreeable, yet there is an intimate little corner in my affections into which it could never penetrate." And later he wrote in a letter to his mother: "I have so often been to Italy, and so often written to you from thence, that it seems quite a platitude to tell you how much I enjoy it, and what a keen delight I felt again this time when I once more trod the soil of this wonderful country; indeed, by the time you get this you will already yourself be in full enjoyment of its pleasures, and though naturally you cannot feel one tittle of my attachment and yearning affection for it, yet you will have all the physical delights of sun and serene skies and a good share of the wonder and admiration at the inexhaustible natural beauties of this garden of the world. I came through Switzerland this time, but as quick as a shot, as I was in a hurry to get home to Italy."

[7] Du Maurier, who took much interest in tracing indications of various racial distinctions in the remarkable people of his time, was troubled on this point. He was convinced that in Leighton existed indications of foreign or Jewish blood, but was quite unable to discover any facts in support of this theory.

[8] Leighton wrote in a letter to his sister from Algiers of the strange sounds which the Moors emit, adding: "Much the same sort of thing is noticeable in the peasants near Rome, whose songs consist (within a definite shape) of long-sustained chest notes that are peculiar in the extreme, and though often harsh, seem to be wonderfully in harmony with the long unbroken lines of the Campagna."

[9] On December 1, 1856, Leighton writes to Steinle: "My Italian journey afforded me in every way the greatest pleasure and edification, and I seem now for the first time to have grasped the greatness of the Campagna and the giant loftiness of Michael Angelo."

[10] "Après de pareilles émotions, il avait besoin d'être seul, de savourer sa joie, de chanter sa liberté définitivement conquise, sur tous les sentiers le long desquels il avait tant gémi, tant lutté.

"Il ne voulut donc pas retourner immédiatement à Saint-Damien. Sortant de la cité par la porte la plus voisine, il s'enfonça dans les sentiers déserts qui grimpent sur les flancs du Mont Subasio. On était aux tout premiers jours du printemps. Il y avait encore çà et là de grandes fondrières de neige, mais sous les ardeurs du soleil de mars l'hiver semblait s'avouer vaincu. Au sein de cette harmonie, mystérieuse et troublante, le cœur de François vibrait délicieusement, tout son être se calmait et s'exaltait; l'âme des choses le caressait doucement et lui versait l'apaisement. Un bonheur inconnu l'envahissait; pour célébrer sa victoire et sa liberté, il remplit bientôt toute la forêt du bruit de ses chants.

"Les émotions trop douces ou trop profondes pour pouvoir être exprimées dans la langue ordinaire, l'homme les chante."—Vie de S. François d'Assise, par Paul Sabatier.

[11] "Notes on Lord Leighton," Cornhill Magazine, March 1897.

[12] The Morning Post of February 4, 1896.

Some light is thrown on Leighton's ancestry by the following letter, written by Sir Baldwyn Leighton to Sir Albert Woods, Garter, at the time when a peerage was bestowed on Frederic Leighton. It deals with the question of associating the name of Stretton with the Barony.

"Tabley House, Knutsford,

January 10, 1896.

"Dear Sir,—In answer to yours of January 9, I beg to say that there are two places called Stretton in the County of Salop; one, now known as Church Stretton, having become a small town, was formerly in the possession of my family through the marriage of John de Leighton, my lineal ancestor, with the daughter and heiress of William Cambray of Stretton in the fourteenth century, whose arms we still quarter (see Herald's Visitation for Shropshire). This no longer belongs to me, having been mortgaged and sold by Sir Thomas Leighton, Kt. Banneret, temp. Hen. VIII. But there is another Stretton in the parish of Alderbury with Cardeston which does still belong to me, and has always belonged to the family from time immemorial. I have been in communication with Sir Frederic Leighton on the subject, and it is my wish that he should adopt the supplemental title of Stretton. According to a pedigree made out by a Shropshire antiquarian some thirty years ago, Sir Frederic's branch descends from the younger son of the John de Leighton who married the Cambray heiress, and [35]who was admitted burgess of Shrewsbury in 1465. Therefore I am of opinion that it is a very proper supplemental title for Sir Frederic to assume.—I remain, yours, &c.,

"Baldwyn Leighton.

"To Sir Albert Woods, Garter."

In 1862, Leighton writes to his mother:—

"You must know that I received some time back a letter from the Rev. Wm. Leighton (address, Luciefelde, Shrewsbury) asking me very politely to give him whatever information I could about our family, as he was making a pedigree of the Leighton family, and was anxious to find out something about a branch that had settled and been lost sight of in London. I answered that I regretted I could give him no definite information on the subject, beyond our belief that we were of a younger branch of the Shropshire Leightons, whose arms and crest we bore, that I knew personally nothing of my family further back than my grandfather, telling him who and what he was. I ended by referring him to Papa, to whom I immediately wrote, telling him the nature of Mr. Leighton's request, and begging him to write to him at once in case he could give him any clue that might facilitate his researches. I then received a second, and very interesting, letter from Mr. L. telling me that he had found in Yorkshire some Leightons (I forget the Christian names, but not Robert) who claimed to descend from the Shropshire stock, and whose crest differed from the Leighton crest exactly as ours does, i.e. in the forward expansion of the right wing of the Wyvern; a peculiarity, by the by, which did not appear to be of weight with him. There was more in this letter which I don't clearly remember, but nothing establishing our claim; this letter I immediately forwarded to you, and since then both myself and Mr. Leighton have been waiting to hear from Papa."

[36]The conclusion arrived at from these inquiries was—that, three or four hundred years ago, the descendants of John de Leighton and the Cambray heiress migrated from Shropshire to Yorkshire, and that Leighton's grandfather, Sir James Leighton, court physician to the Emperor Nicholas of Russia, was a descendant of this branch. Dr. Leighton, the artist's father, married the daughter of George Augustus Nash of Edmonton. He and his wife, early in their married life, went to St. Petersburg, and it was supposed that he would probably succeed his father as court physician to the Czar, who favoured Sir James Leighton with his intimacy; but the climate of St. Petersburg not suiting Mrs. Leighton's health, they remained there but a few years. It was at St. Petersburg that the two eldest children were born, Fanny, who died young, and Alexandra, the god-child of the Empress Alexandra, who became Mrs. Sutherland Orr. From St. Petersburg, the family moved to Scarborough, and it was at Scarborough, on December 3, 1830, that the most famous member of the Leighton family was born. The question as to which was the actual house in which the event took place was satisfactorily settled at the time when Leighton was raised to the peerage, in letters which appeared in the press,—one containing the testimony of Mrs. Anne Thorley, who was in Dr. Leighton's service for three years with the family at Scarborough, and for two years after they moved to London. She affirms that Leighton was born in the house in Brunswick Terrace, now numbered 13, but which at that time consisted only of three houses. Mrs. Thorley adds, "Fred's mother was a splendid lady—such a good one with her children, and most affectionate."

A second son named James, who died in his infancy, was also born at Scarborough, and five years after the birth of Leighton his younger sister Augusta, now Mrs. Matthews, was born in London.

[37]Dr. Leighton had every prospect of excelling among those most distinguished in his profession. Deafness, however, by which he was unfortunately attacked about that time, made it impossible for him to practise any longer as a physician. Deprived of his active work, he turned his attention to more abstract lines of study, and to philosophy.

In 1840, Mrs. Leighton, after a severe illness, required a drier climate than that of England, and the family travelled on the Continent, visiting Germany, Switzerland, and Italy.

Family annals record the delight with which Leighton, the boy of ten, enjoyed the beauty of nature in Switzerland, the flowers and everything he saw in the land of mountains. When he reached Rome, the buildings, the fountains, the ruins, the models awaiting hire on the Piazza di Spagna, fascinated him, and he filled many sketch-books with records of all the picturesque scenes that struck him as so new and wonderful. From earliest days, drawing was Leighton's greatest amusement, and he had it always in his own mind that he would be an artist and nothing else. When in Rome, he was allowed to study drawing under Signor Meli, but his father insisted on other lessons being carried on with regularity and industry. We hear of his elder sister and Leighton learning Latin together from a young priest. Dr. Leighton had a commanding intelligence, and made his will felt. As with many fond fathers who centre their chief interest on an only son, and foster thoughts of a notable future for him, Dr. Leighton seems to have felt that the greater his interest and affection, the greater must be the exercise of strict discipline over his boy. Leighton received, to say the least, a stern upbringing from his father, mitigated, however, by the greatest tenderness from his mother. The boy's will respecting his future career proved sufficient for the occasion, and he had reason to be thankful that the general knowledge, which Dr. Leighton insisted on his acquiring, was instilled at so early an age. From the time he was ten years [38]old he was made to study the classics, and at twelve he spoke French and Italian as fluently as English. Dr. Leighton had himself taught the boy anatomy, ever cherishing the hope that he would, when he came to years of discretion, renounce the idea of being an artist, and follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather by becoming a doctor. In either case a knowledge of anatomy was thought necessary, and, in after years, Leighton declared he knew much more anatomy when he was fourteen than he did when he was President of the Royal Academy. "I owe," he said, "my knowledge to my father. He would teach me the names of the bones and the muscles. He would show them to me in action and in repose; then I would have to draw them from memory; until my memory drawing was perfect, he would not let it pass."

The family returned to England for the summer of 1841, spending it at the paternal grandfather's country house at Greenford; and during the following winter Leighton studied at the University College School in London. Mrs. Leighton's health again declined in England, and the family migrated to Germany, the country chosen by Dr. Leighton as that in which the education of the children could be best carried forward. Leighton studied under tutors at Berlin, it being only in his spare moments that he found time to sketch, or to visit the galleries. Then followed a move to Frankfort, and thence to Florence. There he was allowed to enter the studio of Bezzuoli and Servolini, celebrated artists in Florence, but of whose real greatness Leighton, even at that early age, entertained his doubts. It was in Florence that the father's will had finally to submit to the son's passion for his vocation. Dr. Leighton was too wise to allow prejudice to affect his serious actions. He could no longer blind himself to the fact, that this desire to be an artist was a vital matter with his son. He felt it would be wrong to try and override the boy's desires without [39]seeking the opinion of an expert on art matters as to whether there was any probability of Leighton excelling. He therefore took him and his drawings to Hiram Powers, the sculptor, for the verdict to be given. The well-known conversation took place after Powers had examined the work.

"Shall I make him a painter?" asked Dr. Leighton.

"Sir, you cannot help yourself; nature has made him one already," answered the sculptor.

"What can he hope for, if I let him prepare for this career?"

"Let him aim at the highest," answered Powers; "he will be certain to get there."

Leighton had won: he had now to prove good his cause. Even though theoretically his father had given in, he yet hoped that, as years went on, a change in his boy's views might come about; but he was allowed to work at the Accademia delle belle Arti, under Bezzuoli and Servolini, and besides continuing his study of anatomy with his father, Leighton attended classes in the hospital under Zanetti. Of this time in Florence, one of his life-long friends, Professor Costa, writes: "I knew, both from himself and from his fellow-students, that at the age of fourteen Leighton studied at the Academy of Florence under Bezzuoli and Servolini, who at this time (1842) had a great reputation. They were celebrated Florentines, excellent good men, but they could give but little light to this star, which was to become one of the first magnitude. Leighton, from his innate kindness, loved and esteemed his old masters much, though not agreeing in the judgment of his fellow-students that they should be considered on the same level as the ancient Florentines. 'And who have you,' said Leighton one day to a certain Bettino (who is still living), 'who resembles your ancient masters?' And Bettino answered, 'We have still to-day our great Michael Angelos, and Raffaels, in Bezzuoli, in Servolini, in [40]Ciseri.' But this boy of twelve years old could not believe this, and one fine day got into the diligence, and left the Academy of Florence to return to England. Although the diligence went at a great pace, his fellow-students followed it on foot, running behind it, crying, 'Come back, Inglesino! come back, Inglesino! come back,' so much was he loved and respected. He did come back, in fact, many times to Italy, which he considered as his second fatherland."