|

|

Artist Index THE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RAKE'S PROGRESS. | |||

| Plate | 1 | Heir taking Possession | 11 |

| " | 2 | Surrounded by Artists | 13 |

| " | 3 | Tavern Scene | 15 |

| " | 4 | Arrested for Debt | 17 |

| " | 5 | Marries an Old Maid | 19 |

| " | 6 | Gaming House | 21 |

| " | 7 | Prison Scene | 23 |

| " | 8 | Mad House | 25 |

| The Distressed Poet | 27 | ||

| The Bench | 29 | ||

| The Laughing Audience | 31 | ||

| Gate of Calais | 33 | ||

| The Politician | 35 | ||

| Taste in High Life | 37 | ||

| HARLOT'S PROGRESS. | |||

| Plate | 1 | 39 | |

| " | 2 | 41 | |

| " | 3 | 43 | |

| " | 4 | 45 | |

| " | 5 | 47 | |

| " | 6 | 49 | |

| The Lecture | 51 | ||

| The Chorus | 53 | ||

| Columbus breaking the Egg | 55 | ||

| Modern Midnight Conversation | 57 | ||

| Consultation of Physicians | 59 | ||

| Portrait of Daniel Lock, Esq. | 61 | ||

| The Enraged Musician | 63 | ||

| Masquerades and Operas | 65 | ||

| TIMES OF THE DAY. | |||

| Morning | 67 | ||

| Noon | 69 | ||

| Evening | 71 | ||

| Night | 73 | ||

| Sigismonda | 75 | ||

| Portrait of Martin Fowkes, Esq. | 77 | ||

| The Cockpit | 78 | ||

| Captain Thomas Coram | 81 | ||

| Country Inn Yard | 83 | ||

| INDUSTRY AND IDLENESS. | |||

| Plate | 1 | 85 | |

| " | 2 | 87 | |

| " | 3 | 89 | |

| " | 4 | 91 | |

| " | 5 | 93 | |

| " | 6 | 95 | |

| " | 7 | 97 | |

| " | 8 | 99 | |

| " | 9 | 101 | |

| " | 10 | 103 | |

| " | 11 | 105 | |

| " | 12 | 107 | |

| Southwark Fair. | 109 | ||

| Garrick as Richard III. | 111 | ||

| FRANCE AND ENGLAND. | |||

| Plate | 1 | France | 113 |

| " | 2 | England | 115 |

Of all the follies in human life, there is none greater than that of extravagance, or profuseness; it being constant labour, without the least ease or relaxation. It bears, indeed, the colour of that which is commendable, and would fain be thought to take its rise from laudable motives, searching indefatigably after true felicity; now as there can be no true felicity without content, it is this which every man is in constant pursuit of; the learned, for instance, in his industrious quest after knowledge; the merchant, in his dangerous voyages; the ambitious, in his passionate pursuit of honour; the conqueror, in his earnest desire of victory; the politician, in his deep-laid designs; the wanton, in his pleasing charms of beauty; the covetous, in his unwearied heaping-up of treasure; and the prodigal, in his general and extravagant indulgence.—Thus far it may be well;—but, so mistaken are we in our road, as to run on in the very opposite tract, which leads directly to our ruin. Whatever else we indulge ourselves in, is attended with some small degree of relish, and has some trifling satisfaction in the enjoyment, but, in this, the farther we go, the more we are lost; and when arrived at the mark proposed, we are as far from the object we pursue, as when we first set out. Here then, are we inexcusable, in not attending to the secret dictates of reason, and in stopping our ears at the timely admonitions of friendship. Headstrong and ungovernable, we pursue our course without intermission; thoughtless and unwary, we see not the dangers that lie immediately before us; but hurry on, even without sight of our object, till[Pg 10] we bury ourselves in that gulf of woe, where perishes at once, health, wealth and virtue, and whose dreadful labyrinths admit of no return.

Struck with the foresight of that misery, attendant on a life of debauchery, which is, in fact, the offspring of prodigality, our author has, in the scenes before us, attempted the reformation of the worldling, by stopping him as it were in his career, and opening to his view the many sad calamities awaiting the prosecution of his proposed scheme of life; he has, in hopes of reforming the prodigal, and at the same time deterring the rising generation, whom Providence may have blessed with earthly wealth, from entering into so iniquitous a course, exhibited the life of a young man, hurried on through a succession of profligate pursuits, for the few years Nature was able to support itself; and this from the instant he might be said to enter into the world, till the time of his leaving it. But, as the vice of avarice is equal to that of prodigality, and the ruin of children is often owing to the indiscretion of their parents, he has opened the piece with a scene, which, at the same time that it exposes the folly of the youth, shews us the imprudence of the father, who is supposed to have hurt the principles of his son, in depriving him of the necessary use of some portion of that gold, he had with penurious covetousness been hoarding up, for the sole purpose of lodging in his coffers.[Pg 11]

Hoadley.

The history opens, representing a scene crowded with all the monuments of avarice, and laying before us a most beautiful contrast, such as is too general in the world, to pass unobserved; nothing being more common than for a son to prodigally squander away that substance his father had, with anxious solicitude, his whole life been amassing.—Here, we see the young heir, at the age of nineteen or twenty, raw from the University, just arrived at home, upon the death of his father. Eager to know the possessions he is master of, the old wardrobes, where things have been rotting time out of mind, are instantly wrenched open; the strong chests are unlocked; the parchments, those securities of treble interest, on which this avaricious monster lent his money, tumbled out; and the bags of gold, which had long been hoarded, with griping care, now exposed to the pilfering hands of those about him. To explain every little mark of usury and covetousness, such as the mortgages, bonds, indentures, &c. the piece of candle stuck on a save-all, on the mantle-piece; the rotten furniture of the room, and the miserable contents of the dusty wardrobe, would be unnecessary: we shall only notice the more striking articles. From the vast quantity of papers, falls an old written journal, where, among other memorandums, we find the following, viz. "May the 5th, 1721. Put off my bad shilling." Hence, we learn, the store this penurious miser set on this trifle: that so penurious is the disposition of the miser, that notwithstanding he may be possessed of many large bags of gold, the fear of losing a single shilling is a continual trouble to him. In one part of the room, a man is hanging it with black cloth, on which are placed escutcheons, by way of dreary ornament; these escutcheons contain the arms of the covetous, viz. three vices, hard screwed, with the motto, "Beware!" On the floor, lie a pair of old shoes, which this sordid wretch is supposed to have long preserved for the weight of iron in the nails, and has been soling with leather cut from the covers of an old Family Bible; an excellent piece of satire, intimating, that such men would sacrifice even their God to the lust of money. From these and some other objects too striking to pass unnoticed, such as the gold[Pg 12] falling from the breaking cornice; the jack and spit, those utensils of original hospitality, locked up, through fear of being used; the clean and empty chimney, in which a fire is just now going to be made for the first time; and the emaciated figure of the cat, strongly mark the natural temper of the late miserly inhabitant, who could starve in the midst of plenty.—But see the mighty change! View the hero of our piece, left to himself, upon the death of his father, possessed of a goodly inheritance. Mark how his mind is affected!—determined to partake of the mighty happiness he falsely imagines others of his age and fortune enjoy; see him running headlong into extravagance, withholding not his heart from any joy; but implicitly pursuing the dictates of his will. To commence this delusive swing of pleasure, his first application is to the tailor, whom we see here taking his measure, in order to trick out his pretty person. In the interim, enters a poor girl (with her mother), whom our hero has seduced, under professions of love and promises of marriage; in hopes of meeting with that kind welcome she had the greatest reason to expect; but he, corrupted with the wealth of which he is now the master, forgets every engagement he once made, finds himself too rich to keep his word; and, as if gold would atone for a breach of honour, is offering money to her mother, as an equivalent for the non-fulfilling of his promise. Not the sight of the ring, given as a pledge of his fidelity; not a view of the many affectionate letters he at one time wrote to her, of which her mother's lap is full; not the tears, nor even the pregnant condition of the wretched girl, could awaken in him one spark of tenderness; but, hard hearted and unfeeling, like the generality of wicked men, he suffers her to weep away her woes in silent sorrow, and curse with bitterness her deceitful betrayer. One thing more we shall take notice of, which is, that this unexpected visit, attended with abuse from the mother, so engages the attention of our youth, as to give the old pettifogger behind him an opportunity of robbing him. Hence we see that one ill consequence is generally attended with another; and that misfortunes, according to the old proverb, seldom come alone.

Mr. Ireland remarks of this plate—"He here presents to us the picture of a young man, thoughtless, extravagant, and licentious; and, in colours equally impressive, paints the destructive consequences of his conduct. The first print most forcibly contrasts two opposite passions; the unthinking negligence of youth, and the sordid avaricious rapacity of age. It brings into one point of view what Mr. Pope so exquisitely describes in his Epistle to Lord Bathurst—

The introduction to this history is well delineated, and the principal figure marked with that easy, unmeaning vacancy of face, which speaks him formed by nature for a DUPE. Ignorant of the value of money, and negligent in his nature, he leaves his bag of untold gold in the reach of an old and greedy pettifogging attorney, who is making an inventory of bonds, mortgages, indentures, &c. This man, with the rapacity so natural to those who disgrace the profession, seizes the first opportunity of plundering his employer. Hogarth had, a few years before, been engaged in a law suit, which gave him some experience of the PRACTICE of those pests of society."

Hoadley.

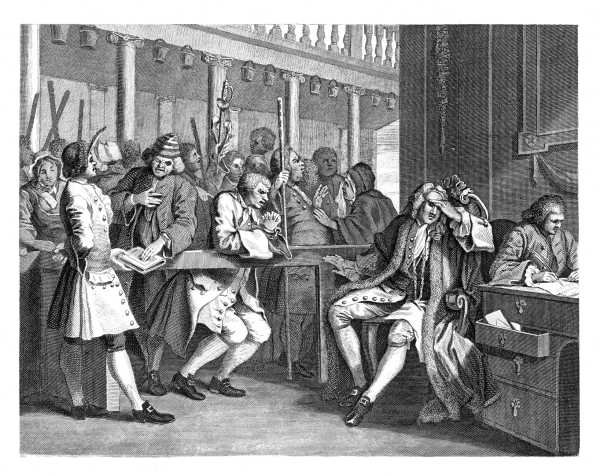

We are next to consider our hero as launched into the world, and having equipped himself with all the necessaries to constitute him a man of taste, he plunges at once into all the fashionable excesses, and enters with spirit into the character he assumes.

The avarice of the penurious father then, in this print, is contrasted by the giddy profusion of his prodigal son. We view him now at his levee, attended by masters of various professions, supposed to be here offering their interested services. The foremost figure is readily known to be a dancing-master; behind him are two men, who at the time when these prints were first published, were noted for teaching the arts of defence by different weapons, and who are here drawn from the life; one of whom is a Frenchman, teacher of the small-sword, making a thrust with his foil; the other an Englishman, master of the quarter-staff; the vivacity of the first, and the cold contempt visible in the face of the second, beautifully describe the natural disposition of the two nations. On the left of the latter stands an improver of gardens, drawn also from the life, offering a plan for that purpose. A taste for gardening, carried to excess, must be acknowledged to have been the ruin of numbers, it being a passion that is seldom, if ever, satisfied, and attended with the greatest expense. In the chair sits a professor of music, at the harpsichord, running over the keys, waiting to give his pupil a lesson; behind whose chair hangs a list of the presents, one Farinelli, an Italian singer, received the next day after his first performance at the Opera House; amongst which, there is notice taken of one, which he received from the hero of our piece, thus: "A gold snuff-box, chased, with the story of Orpheus charming the brutes, by J. Rakewell, esq." By these mementos of extravagance and pride, (for gifts of this kind proceed oftener from ostentation than generosity,) and by the engraved frontispiece to a poem, dedicated to our fashionable spendthrift, lying on the floor, which represents the ladies of Britain sacrificing their hearts to the idol Farinelli, crying out, with the greatest earnestness, "one G—d, one Farinelli," we are given to understand the prevailing dissipation and luxury of the times. Near the principal figure in this plate is that of him, with one hand on his breast, the other on his sword, whom we may easily discover to be a bravo; he is represented as having brought a letter of recommendation, as one disposed to under[Pg 14]take all sorts of service. This character is rather Italian than English; but is here introduced to fill up the list of persons at that time too often engaged in the service of the votaries of extravagance and fashion. Our author would have it imagined in the interval between the first scene and this, that the young man whose history he is painting, had now given himself up to every fashionable extravagance; and among others, he had imbibed a taste for cock-fighting and horse-racing; two amusements, which, at that time, the man of fashion could not dispense with. This is evident, from his rider bringing in a silver punch-bowl, which one of his horses is supposed to have won, and his saloon being ridiculously ornamented with the portraits of celebrated cocks. The figures in the back part of this plate represent tailors, peruke-makers, milliners, and such other persons as generally fill the antichamber of a man of quality, except one, who is supposed to be a poet, and has written some panegyric on the person whose levee he attends, and who waits for that approbation he already vainly anticipates. Upon the whole, the general tenor of this scene is to teach us, that the man of fashion is too often exposed to the rapacity of his fellow creatures, and is commonly a dupe to the more knowing part of the world.

"How exactly," says Mr. Ireland, "does Bramston describe the character in his Man of Taste:—

"Of the expression in this print, we cannot speak more highly than it deserves. Every character is marked with its proper and discriminative stamp. It has been said by a very judicious critic (the Rev. Mr. Gilpin) from whom it is not easy to differ without being wrong, that the hero of this history, in the first plate of the series, is unmeaning, and in the second ungraceful. The fact is admitted; but, for so delineating him, the author is entitled to our praise, rather than our censure. Rakewell's whole conduct proves he was a fool, and at that time he had not learned how to perform an artificial character; he therefore looks as he is, unmeaning, and uninformed. But in the second plate he is ungraceful.—Granted. The ill-educated son of so avaricious a father could not have been introduced into very good company; and though, by the different teachers who surround him, it evidently appears that he wishes to assume the character of a gentleman, his internal feelings tell him he has not attained it. Under that consciousness, he is properly and naturally represented as ungraceful, and embarrassed in his new situation."

Mr. Ireland having, in his description of this Plate, incorporated whatever is of value in Dr. Trusler's text, with much judicious observation and criticism of his own, the Editor has taken the former verbatim.

"This Plate exhibits our licentious prodigal engaged in one of his midnight festivities: forgetful of the past, and negligent of the future, he riots in the present. Having poured his libation to Bacchus, he concludes the evening orgies in a sacrifice at the Cyprian shrine; and, surrounded by the votaries of Venus, joins in the unhallowed mysteries of the place. The companions of his revelry are marked with that easy, unblushing effrontery, which belongs to the servants of all work in the isle of Paphos;—for the maids of honour they are not sufficiently elevated.

"He may be supposed, in the phrase of the day, to have beat the rounds, overset a constable, and conquered a watchman, whose staff and lantern he has brought into the room, as trophies of his prowess. In this situation he is robbed of his watch by the girl whose hand is in his bosom; and, with that adroitness peculiar to an old practitioner, she conveys her acquisition to an accomplice, who stands behind the chair.

"Two of the ladies are quarrelling; and one of them delicately spouts wine in the face of her opponent, who is preparing to revenge the affront with a knife, which, in a posture of threatening defiance, she grasps in her hand. A third, enraged at being neglected, holds a lighted candle to a map of the globe, determined to set the world on fire, though she perish in the conflagration! A fourth is undressing. The fellow bringing in a pewter dish, as part of the apparatus of this elegant and Attic entertainment, a blind harper, a trumpeter, and a ragged ballad-singer, roaring out an obscene song, complete this motley group.

"This design may be a very exact representation of what were then the nocturnal amusements of a brothel;—so different are the manners of former and present times, that I much question whether a similar exhibition is now to be seen in any tavern of the metropolis. That we are less licentious than our predecessors, I dare not affirm; but we are certainly more delicate in the pursuit of our pleasures.[Pg 16]

"The room is furnished with a set of Roman emperors,—they are not placed in their proper order; for in the mad revelry of the evening, this family of frenzy have decollated all of them, except Nero; and his manners had too great a similarity to their own, to admit of his suffering so degrading an insult; their reverence for virtue induced them to spare his head. In the frame of a Cæsar they have placed a portrait of Pontac, an eminent cook, whose great talents being turned to heightening sensual, rather than mental enjoyments, he has a much better chance of a votive offering from this company, than would either Vespasian or Trajan.

"The shattered mirror, broken wine-glasses, fractured chair and cane; the mangled fowl, with a fork stuck in its breast, thrown into a corner, and indeed every accompaniment, shews, that this has been a night of riot without enjoyment, mischief without wit, and waste without gratification.

"With respect to the drawing of the figures in this curious female coterie, Hogarth evidently intended several of them for beauties; and of vulgar, uneducated, prostituted beauty, he had a good idea. The hero of our tale displays all that careless jollity, which copious draughts of maddening wine are calculated to inspire; he laughs the world away, and bids it pass. The poor dupe, without his periwig, in the back-ground, forms a good contrast of character: he is maudlin drunk, and sadly sick. To keep up the spirit of unity throughout the society, and not leave the poor African girl entirely neglected, she is making signs to her friend the porter, who perceives, and slightly returns, her love-inspiring glance. This print is rather crowded,—the subject demanded it should be so; some of the figures, thrown into shade, might have helped the general effect, but would have injured the characteristic expression."

The career of dissipation is here stopped. Dressed in the first style of the ton, and getting out of a sedan-chair, with the hope of shining in the circle, and perhaps forwarding a former application for a place or a pension, he is arrested! To intimate that being plundered is the certain consequence of such an event, and to shew how closely one misfortune treads upon the heels of another, a boy is at the same moment stealing his cane.

The unfortunate girl whom he basely deserted, is now a milliner, and naturally enough attends in the crowd, to mark the fashions of the day. Seeing his distress, with all the eager tenderness of unabated love, she flies to his relief. Possessed of a small sum of money, the hard earnings of unremitted industry, she generously offers her purse for the liberation of her worthless favourite. This releases the captive beau, and displays a strong instance of female affection; which, being once planted in the bosom, is rarely eradicated by the coldest neglect, or harshest cruelty.

The high-born, haughty Welshman, with an enormous leek, and a countenance keen and lofty as his native mountains, establishes the chronology, and fixes the day to be the first of March; which being sacred to the titular saint of Wales, was observed at court.

Mr. Nichols remarks of this plate:—"In the early impressions, a shoe-black steals the Rake's cane. In the modern ones, a large group of sweeps, and black-shoe boys, are introduced gambling on the pavement; near them a stone inscribed Black's, a contrast to White's gaming-house, against which a flash of lightning is pointed. The curtain in the window of the sedan-chair is thrown back. This plate is likewise found in an intermediate state; the sky being made unnaturally obscure, with an attempt to introduce a shower of rain, and lightning very aukwardly represented. It is supposed to be a first proof after the insertion of the group of blackguard gamesters; the window of the chair being only marked for an alteration that was afterwards made in it. Hogarth appears to have so far[Pg 18] spoiled the sky, that he was obliged to obliterate it, and cause it to be engraved over again by another hand."

Mr. Gilpin observes:—"Very disagreeable accidents often befal gentlemen of pleasure. An event of this kind is recorded in the fourth print, which is now before us. Our hero going, in full dress, to pay his compliments at court on St. David's day, was accosted in the rude manner which is here represented.—The composition is good. The form of the group, made up of the figures in action, the chair, and the lamplighter, is pleasing. Only, here we have an opportunity of remarking, that a group is disgusting when the extremities of it are heavy. A group in some respects should resemble a tree. The heavier part of the foliage (the cup, as the landscape-painter calls it) is always near the middle; the outside branches, which are relieved by the sky, are light and airy. An inattention to this rule has given a heaviness to the group before us. The two bailiffs, the woman, and the chairman, are all huddled together in that part of the group which should have been the lightest; while the middle part, where the hand holds the door, wants strength and consistence. It may be added too, that the four heads, in the form of a diamond, make an unpleasing shape. All regular figures should be studiously avoided.—The light had been well distributed, if the bailiff holding the arrest, and the chairman, had been a little lighter, and the woman darker. The glare of the white apron is disagreeable.—We have, in this print, some beautiful instances of expression. The surprise and terror of the poor gentleman is apparent in every limb, as far as is consistent with the fear of discomposing his dress. The insolence of power in one of the bailiffs, and the unfeeling heart, which can jest with misery, in the other, are strongly marked. The self-importance, too, of the honest Cambrian is not ill portrayed; who is chiefly introduced to settle the chronology of the story.—In pose of grace, we have nothing striking. Hogarth might have introduced a degree of it in the female figure: at least he might have contrived to vary the heavy and unpleasing form of her drapery.—The perspective is good, and makes an agreeable shape."

To be thus degraded by the rude enforcement of the law, and relieved from an exigence by one whom he had injured, would have wounded, humbled, I had almost said reclaimed, any man who had either feeling or elevation of mind; but, to mark the progression of vice, we here see this depraved, lost character, hypocritically violating every natural feeling of the soul, to recruit his exhausted finances, and marrying an old and withered Sybil, at the sight of whom nature must recoil.

The ceremony passes in the old church, Mary-le-bone, which was then considered at such a distance from London, as to become the usual resort of those who wished to be privately married; that such was the view of this prostituted young man, may be fairly inferred from a glance at the object of his choice. Her charms are heightened by the affectation of an amorous leer, which she directs to her youthful husband, in grateful return for a similar compliment which she supposes paid to herself. This gives her face much meaning, but meaning of such a sort, that an observer being ask, "How dreadful must be this creature's hatred?" would naturally reply, "How hateful must be her love!"

In his demeanor we discover an attempt to appear at the altar with becoming decorum: but internal perturbation darts through assumed tranquillity, for though he is plighting his troth to the old woman, his eyes are fixed on the young girl who kneels behind her.

The parson and clerk seem made for each other; a sleepy, stupid solemnity marks every muscle of the divine, and the nasal droning of the lay brother is most happily expressed. Accompanied by her child and mother, the unfortunate victim of his seduction is here again introduced, endeavouring to enter the church, and forbid the banns. The opposition made by an old pew-opener, with her bunch of keys, gave the artist a good opportunity for indulging his taste in the burlesque, and he has not neglected it.

A dog (Trump, Hogarth's favorite), paying his addresses to a one-eyed quadruped of his own species, is a happy parody of the unnatural union going on in the church.

The commandments are broken: a crack runs near the tenth, which says, Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife; a prohibition in the present case hardly necessary.[Pg 20] The creed is destroyed by the damps of the church; and so little attention has been paid to the poor's box, that it is covered with a cobweb! These three high-wrought strokes of satirical humour were perhaps never equalled by any exertion of the pencil; excelled they cannot be.

On one of the pew doors is the following curious specimen of church-yard poetry, and mortuary orthography.

This is a correct copy of the inscription. Part of these lines, in raised letters, now form a pannel in the wainscot at the end of the right-hand gallery, as the church is entered from the street. The mural monument of the Taylor's, composed of lead, gilt over, is still preserved: it is seen in Hogarth's print, just under the window.

A glory over the bride's head is whimsical.

The bay and holly, which decorate the pews, give a date to the period, and determine this preposterous union of January with June, to have taken place about the time of Christmas;

Addison would have classed her among the evergreens of the sex.

It has been observed, that "the church is too small, and the wooden post, which seems to have no use, divides the picture very disagreeably." This cannot be denied: but it appears to be meant as an accurate representation of the place, and the artist delineated what he saw.

The grouping is good, and the principal figure has the air of a gentleman. The light is well distributed, and the scene most characteristically represented.

The commandments being represented as broken, might probably give the hint to a lady's reply, on being told that thieves had the preceding night broken into the church, and stolen the communion-plate, and the ten commandments. "I suppose," added the informant, "that they may melt and sell the plate; but can you divine for what possible purpose they could steal the commandments?"—"To break them, to be sure," replied she;—"to break them."

Though now, from the infatuated folly of his antiquated wife, in possession of a fortune, he is still the slave of that baneful vice, which, while it enslaves the mind, poisons the enjoyments, and sweeps away the possessions of its deluded votaries. Destructive as the earthquake which convulses nature, it overwhelms the pride of the forest, and engulfs the labours of the architect.

Newmarket and the cockpit were the scenes of his early amusements; to crown the whole, he is now exhibited at a gaming-table, where all is lost! His countenance distorted with agony, and his soul agitated almost to madness, he imprecates vengeance upon his own head.

That he should be deprived of all he possessed in such a society as surround him, is not to be wondered at. One of the most conspicuous characters appears, by the pistol in his pocket, to be a highwayman: from the profound stupor of his countenance, we are certain he also is a losing gamester; and so absorbed in reflection, that neither the boy who brings him a glass of water, nor the watchman's cry of "Fire!" can arouse him from his reverie. Another of the party is marked for one of those well-dressed continental adventurers, who, being unable to live in their own country, annually pour into this, and with no other requisites than a quick eye, an adroit hand, and an undaunted forehead, are admitted into what is absurdly enough called good company.

At the table a person in mourning grasps his hat, and hides his face, in the agony of repentance, not having, as we infer from his weepers, received that legacy of which[Pg 22] he is now plundered more than "a little month." On the opposite side is another, on whom fortune has severely frowned, biting his nails in the anguish of his soul. The fifth completes the climax; he is frantic; and with a drawn sword endeavours to destroy a pauvre miserable whom he supposes to have cheated him, but is prevented by the interposition of one of those staggering votaries of Bacchus who are to be found in every company where there is good wine; and gaming, like the rod of Moses, so far swallows up every other passion, that the actors, engrossed by greater objects, willingly leave their wine to the audience.

In the back-ground are two collusive associates, eagerly dividing the profits of the evening.

A nobleman in the corner is giving his note to an usurer. The lean and hungry appearance of this cent. per cent. worshipper of the golden calf, is well contrasted by the sleek, contented vacancy of so well-employed a legislator of this great empire. Seated at the table, a portly gentleman, of whom we see very little, is coolly sweeping off his winnings.

So engrossed is every one present by his own situation, that the flames which surround them are disregarded, and the vehement cries of a watchman entering the room, are necessary to rouse their attention to what is generally deemed the first law of nature, self-preservation.

Mr. Gilpin observes:—"The fortune, which our adventurer has just received, enables him to make one push more at the gaming-table. He is exhibited, in the sixth print, venting curses on his folly for having lost his last stake.—This is, upon the whole, perhaps, the best print of the set. The horrid scene it describes, was never more inimitably drawn. The composition is artful, and natural. If the shape of the whole be not quite pleasing, the figures are so well grouped, and with so much ease and variety, that you cannot take offence.

"The expression, in almost every figure, is admirable; and the whole is a strong representation of the human mind in a storm. Three stages of that species of madness which attends gaming, are here described. On the first shock, all is inward dismay. The ruined gamester is represented leaning against a wall, with his arms across, lost in an agony of horror. Perhaps never passion was described with so much force. In a short time this horrible gloom bursts into a storm of fury: he tears in pieces what comes next him; and, kneeling down, invokes curses upon himself. He next attacks others; every one in his turn whom he imagines to have been instrumental in his ruin.—The eager joy of the winning gamesters, the attention of the usurer, the vehemence of the watchman, and the profound reverie of the highwayman, are all admirably marked. There is great coolness, too, expressed in the little we see of the fat gentleman at the end of the table."

By a very natural transition Mr. Hogarth has passed his hero from a gaming house into a prison—the inevitable consequence of extravagance. He is here represented in a most distressing situation, without a coat to his back, without money, without a friend to help him. Beggared by a course of ill-luck, the common attendant on the gamester, having first made away with every valuable he was master of, and having now no other resource left to retrieve his wretched circumstances, he at last, vainly promising himself success, commences author, and attempts, though inadequate to the task, to write a play, which is lying on the table, just returned with an answer from the manager of the theatre, to whom he had offered it, that his piece would by no means do. Struck speechless with this disastrous occurrence, all his hopes vanish, and his most sanguine expectations are changed into dejection of spirit. To heighten his distress, he is approached by his wife, and bitterly upbraided for his perfidy in concealing from her his former connexions (with that unhappy girl who is here present with her child, the innocent offspring of her amours, fainting at the sight of his misfortunes, being unable to relieve him farther), and plunging her into those difficulties she never shall be able to surmount. To add to his misery, we see the under-turnkey pressing him for his prison fees, or garnish-money, and the boy refusing to leave the beer he ordered, without being first paid for it. Among those assisting the fainting mother, one of whom we observe clapping her hand, another applying the drops, is a man crusted over, as it were, with the rust of a gaol, supposed to have started from his dream, having been disturbed by the noise at a time when he was settling some affairs of state; to have left his great plan unfinished, and to have hurried to the assistance of distress. We are told, by the papers falling from his lap, one of which contains a scheme for paying the national debt, that his confinement is owing to that itch of politics some persons are troubled with, who will neglect their own affairs, in order to busy them[Pg 24]selves in that which noways concerns them, and which they in no respect understand, though their immediate ruin shall follow it: nay, so infatuated do we find him, so taken up with his beloved object, as not to bestow a few minutes on the decency of his person. In the back of the room is one who owes his ruin to an indefatigable search after the philosopher's stone. Strange and unaccountable!—Hence we are taught by these characters, as well as by the pair of human wings on the tester of the bed, that scheming is the sure and certain road to beggary: and that more owe their misfortunes to wild and romantic notions, than to any accident they meet with in life.

In this upset of his life, and aggravation of distress, we are to suppose our prodigal almost driven to desperation. Now, for the first time, he feels the severe effects of pinching cold and griping hunger. At this melancholy season, reflection finds a passage to his heart, and he now revolves in his mind the folly and sinfulness of his past life;—considers within himself how idly he has wasted the substance he is at present in the utmost need of;—looks back with shame on the iniquity of his actions, and forward with horror on the rueful scene of misery that awaits him; until his brain, torn with excruciating thought, loses at once its power of thinking, and falls a sacrifice to merciless despair.

Mr. Ireland remarks, on the plate before us:—"Our improvident spendthrift is now lodged in that dreary receptacle of human misery,—a prison. His countenance exhibits a picture of despair; the forlorn state of his mind is displayed in every limb, and his exhausted finances, by the turnkey's demand of prison fees, not being answered, and the boy refusing to leave a tankard of porter, unless he is paid for it.

"We see by the enraged countenance of his wife, that she is violently reproaching him for having deceived and ruined her. To crown this catalogue of human tortures, the poor girl whom he deserted, is come with her child—perhaps to comfort him,—to alleviate his sorrows, to soothe his sufferings:—but the agonising view is too much for her agitated frame; shocked at the prospect of that misery which she cannot remove, every object swims before her eyes,—a film covers the sight,—the blood forsakes her cheeks—her lips assume a pallid hue,—and she sinks to the floor of the prison in temporary death. What a heart-rending prospect for him by whom this is occasioned!

"The wretched, squalid inmate, who is assisting the fainting female, bears every mark of being naturalised to the place; out of his pocket hangs a scroll, on which is inscribed, 'A scheme to pay the National Debt, by J. L. now a prisoner in the Fleet.' So attentive was this poor gentleman to the debts of the nation, that he totally forgot his own. The cries of the child, and the good-natured attentions of the women, heighten the interest, and realise the scene. Over the group are a large pair of wings, with which some emulator of Dedalus intended to escape from his confinement; but finding them inadequate to the execution of his project, has placed them upon the tester of his bed. They would not exalt him to the regions of air, but they o'ercanopy him on earth. A chemist in the back-ground, happy in his views, watching the moment of projection, is not to be disturbed from his dream by any thing less than the fall of the roof, or the bursting of his retort;—and if his dream affords him felicity, why should he be awakened? The bed and gridiron, those poor remnants of our miserable spendthrift's wretched property, are brought here as necessary in his degraded situation; on one he must try to repose his wearied frame, on the other, he is to dress his scanty meal."

See our hero then, in the scene before us, raving in all the dismal horrors of hopeless insanity, in the hospital of Bethlehem, the senate of mankind, where each man may find a representative; there we behold him trampling on the first great law of nature, tearing himself to pieces with his own hands, and chained by the leg to prevent any further mischief he might either do to himself or others. But in this scene, dreary and horrid as are its accompaniments, he is attended by the faithful and kind-hearted female whom he so basely betrayed. In the first plate we see him refuse her his promised hand. In the fourth, she releases him from the harpy fangs of a bailiff; she is present at his marriage; and in the hope of relieving his distress, she follows him to a prison. Our artist, in this scene of horror, has taken an opportunity of pointing out to us the various causes of mental blindness; for such, surely, it may be called, when the intuitive faculties are either destroyed or impaired. In one of the inner rooms of this gallery is a despairing wretch, imploring Heaven for mercy, whose brain is crazed with lip-labouring superstition, the most dreadful enemy of human kind; which, attended with ignorance, error, penance and indulgence, too often deprives its unhappy votaries of their senses. The next in view is one man drawing lines upon a wall, in order, if possible, to find out the longitude; and another, before him, looking through a paper, by way of a telescope. By these expressive figures we are given to understand that such is the misfortune of man, that while, perhaps, the aspiring soul is pursuing some lofty and elevated conception, soaring to an uncommon pitch, and teeming with some grand discovery, the ferment often proves too strong for the feeble brain to support, and lays the whole magazine of notions and images in wild confusion. This melancholy group is completed by the crazy tailor, who is staring at the mad astronomer with a sort of[Pg 26] wild astonishment, wondering, through excess of ignorance, what discoveries the heavens can possibly afford; proud of his profession, he has fixed a variety of patterns in his hat, by way of ornament; has covered his poor head with shreds, and makes his measure the constant object of his attention. Behind this man stands another, playing on the violin, with his book upon his head, intimating that too great a love for music has been the cause of his distraction. On the stairs sits another, crazed by love, (evident from the picture of his beloved object round his neck, and the words "charming Betty Careless" upon the bannisters, which he is supposed to scratch upon every wall and every wainscot,) and wrapt up so close in melancholy pensiveness, as not even to observe the dog that is flying at him. Behind him, and in the inner room, are two persons maddened with ambition. These men, though under the influence of the same passion, are actuated by different notions; one is for the papal dignity, the other for regal; one imagines himself the Pope, and saying mass; the other fancies himself a King, is encircled with the emblem of royalty, and is casting contempt on his imaginary subjects by an act of the greatest disdain. To brighten this distressful scene, and draw a smile from him whose rigid reasoning might condemn the bringing into public view this blemish of humanity, are two women introduced, walking in the gallery, as curious spectators of this melancholy sight; one of whom is supposed, in a whisper, to bid the other observe the naked man, which she takes an opportunity of doing by a leer through the sticks of her fan.

Thus, imagining the hero of our piece to expire raving mad, the story is finished, and little else remains but to close it with a proper application. Reflect then, ye parents, on this tragic tale; consider with yourselves, that the ruin of a child is too often owing to the imprudence of a father. Had the young man, whose story we have related, been taught the proper use of money, had his parent given him some insight into life, and graven, as it were, upon his heart, the precepts of religion, with an abhorrence of vice, our youth would, in all probability, have taken a contrary course, lived a credit to his friends, and an honour to his country.

This Plate describes, in the strongest colours, the distress of an author without friends to patronise him. Seated upon the side of his bed, without a shirt, but wrapped in an old night-gown, he is now spinning a poem upon "Riches:" of their use he probably knoweth little; and of their abuse,—if judgment can be formed from externals,—certes, he knoweth less. Enchanted, impressed, inspired with his subject, he is disturbed by a nymph of the lactarium. Her shrill-sounding voice awakes one of the little loves, whose chorus disturbs his meditations. A link of the golden chain is broken!—a thought is lost!—to recover it, his hand becomes a substitute for the barber's comb:—enraged at the noise, he tortures his head for the fleeting idea; but, ah! no thought is there!

Proudly conscious that the lines already written are sterling, he possesses by anticipation the mines of Peru, a view of which hangs over his head. Upon the table we see "Byshe's Art of Poetry;" for, like the pack-horse, who cannot travel without his bells, he cannot climb the hill of Parnassus without his jingling-book. On the floor lies the "Grub-street Journal," to which valuable repository of genius and taste he is probably a contributor. To show that he is a master of the PROFOUND, and will envelope his subject in a cloud, his pipe and tobacco-box, those friends to cogitation deep, are close to him.

His wife, mending that part of his dress, in the pockets of which the affluent keep their gold, is worthy of a better fate. Her figure is peculiarly interesting. Her face, softened by adversity, and marked with domestic care, is at this moment agitated by the appearance of a boisterous woman, insolently demanding payment of the milk-tally. In the excuse she returns, there is a mixture of concern, complacency, and mortification. As an addition to the distresses of this poor family, a dog is stealing the remnant of mutton incautiously left upon a chair.

The sloping roof, and projecting chimney, prove the throne of this inspired bard to be high above the crowd;—it is a garret. The chimney is ornamented with a dare for larks, and a book; a loaf, the tea-equipage, and a saucepan, decorate the shelf.[Pg 28] Before the fire hangs half a shirt, and a pair of ruffled sleeves. His sword lies on the floor; for though our professor of poetry waged no war, except with words, a sword was, in the year 1740, a necessary appendage to every thing which called itself "gentleman." At the feet of his domestic seamstress, the full-dress coat is become the resting-place of a cat and two kittens: in the same situation is one stocking, the other is half immersed in the washing-pan. The broom, bellows, and mop, are scattered round the room. The open door shows us that their cupboard is unfurnished, and tenanted by a hungry and solitary mouse. In the corner hangs a long cloak, well calculated to conceal the threadbare wardrobe of its fair owner.

Mr. Hogarth's strict attention to propriety of scenery, is evinced by the cracked plaistering of the walls, broken window, and uneven floor, in the miserable habitation of this poor weaver of madrigals. When this was first published, the following quotation from Pope's "Dunciad" was inscribed under the print:

All his books, amounting to only four, was, I suppose, the artist's reason for erasing the lines.

It having been universally acknowledged that Mr. Hogarth was one of the most ingenious painters of his age, and a man possessed of a vast store of humour, which he has sufficiently shown and displayed in his numerous productions; the general approbation his works receive, is not to be wondered at. But, as owing to the false notions of the public, not thoroughly acquainted with the true art of painting, he has been often called a caricaturer; when, in reality, caricatura was no part of his profession, he being a true copier of Nature; to set this matter right, and give the world a just definition of the words, character, caricatura, and outré, in which humorous painting principally consists, and to show their difference of meaning, he, in the year 1758, published this print; but, as it did not quite answer his purpose, giving an illustration of the word character only, he added, in the year 1764, the group of heads above, which he never lived to finish, though he worked upon it the day before his death. The lines between inverted commas are our author's own words, and are engraved at the bottom of the plate.

"There are hardly any two things more essentially different than character and caricatura; nevertheless, they are usually confounded, and mistaken for each other; on which account this explanation is attempted.

"It has ever been allowed, that when a character is strongly marked in the living face, it may be considered as an index of the mind, to express which, with any degree of justness, in painting, requires the utmost efforts of a great master. Now that, which has of late years got the name of caricatura, is, or ought to be, totally divested of every stroke that hath a tendency to good drawing; it may be said to be a species of lines that are produced, rather by the hand of chance, than of skill; for the early scrawlings of a child, which do but barely hint the idea of a human face, will always be found to be like some person or other, and will often form such a comical resemblance, as, in all probability, the most eminent caricaturers of these times will not be[Pg 30] able to equal, with design; because their ideas of objects are so much more perfect than children's, that they will, unavoidably, introduce some kind of drawing; for all the humorous effects of the fashionable manner of caricaturing, chiefly depend on the surprise we are under, at finding ourselves caught with any sort of similitude in objects absolutely remote in their kind. Let it be observed, the more remote in their nature, the greater is the excellence of these pieces. As a proof of this, I remember a famous caricatura of a certain Italian singer, that struck at first sight, which consisted only of a straight perpendicular stroke, with a dot over. As to the French word outré, it is different from the rest, and signifies nothing more than the exaggerated outlines of a figure, all the parts of which may be, in other respects, a perfect and true picture of nature. A giant or a dwarf may be called a common man, outré. So any part, as a nose, or a leg, made bigger, or less than it ought to be, is that part outré, which is all that is to be understood by this word, injudiciously used to the prejudice of character."—Analysis of Beauty, chap. vi.

To prevent these distinctions being looked upon as dry and unentertaining, our author has, in this group of faces, ridiculed the want of capacity among some of our judges, or dispensers of the law, whose shallow discernment, natural disposition, or wilful inattention, is here perfectly described in their faces. One is amusing himself in the course of trial, with other business; another, in all the pride of self-importance, is examining a former deposition, wholly inattentive to that before him; the next is busied in thoughts quite foreign to the subject; and the senses of the last are locked fast in sleep.

The four sages on the Bench, are intended for Lord Chief Justice Sir John Willes, the principal figure; on his right hand, Sir Edward Clive; and on his left, Mr. Justice Bathurst, and the Hon. William Noel.

"From the first print that Hogarth engraved, to the last that he published, I do not think," says Mr. Ireland, "there is one, in which character is more displayed than in this very spirited little etching. It is much superior to the more delicate engravings from his designs by other artists, and I prefer it to those that were still higher finished by his own burin.

"The prim coxcomb with an enormous bag, whose favours, like those of Hercules between Virtue and Vice, are contended for by two rival orange girls, gives an admirable idea of the dress of the day; when, if we may judge from this print, our grave forefathers, defying Nature, and despising convenience, had a much higher rank in the temple of Folly than was then attained by their ladies. It must be acknowledged that, since that period, the softer sex have asserted their natural rights; and, snatching the wreath of fashion from the brow of presuming man, have tortured it into such forms that, were it possible, which certes it is not, to disguise a beauteous face——But to the high behest of Fashion all must bow.

"Governed by this idol, our beau has a cuff that, for a modern fop, would furnish fronts for a waistcoat, and a family fire-screen might be made of his enormous bag. His bare and shrivelled neck has a close resemblance to that of a half-starved greyhound; and his face, figure, and air, form a fine contrast to the easy and degagée assurance of the Grisette whom he addresses.

"The opposite figure, nearly as grotesque, though not quite so formal as its companion, presses its left hand upon its breast, in the style of protestation; and, eagerly contemplating the superabundant charms of a beauty of Rubens's school, presents her with a pinch of comfort. Every muscle, every line of his countenance, is acted upon by affectation and grimace, and his queue bears some resemblance to an ear-trumpet.

"The total inattention of these three polite persons to the business of the stage, which at this moment almost convulses the children of Nature who are seated in the[Pg 32] pit, is highly descriptive of that refined apathy which characterises our people of fashion, and raises them above those mean passions that agitate the groundlings.

"One gentleman, indeed, is as affectedly unaffected as a man of the first world. By his saturnine cast of face, and contracted brow, he is evidently a profound critic, and much too wise to laugh. He must indisputably be a very great critic; for, like Voltaire's Poccocurante, nothing can please him; and, while those around open every avenue of their minds to mirth, and are willing to be delighted, though they do not well know why, he analyses the drama by the laws of Aristotle, and finding those laws are violated, determines that the author ought to be hissed, instead of being applauded. This it is to be so excellent a judge; this it is which gives a critic that exalted gratification which can never be attained by the illiterate,—the supreme power of pointing out faults, where others discern nothing but beauties, and preserving a rigid inflexibility of muscle, while the sides of the vulgar herd are shaking with laughter. These merry mortals, thinking with Plato that it is no proof of a good stomach to nauseate every aliment presented them, do not inquire too nicely into causes, but, giving full scope to their risibility, display a set of features more highly ludicrous than I ever saw in any other print. It is to be regretted that the artist has not given us some clue by which we might have known what was the play which so much delighted his audience: I should conjecture that it was either one of Shakespear's comedies, or a modern tragedy. Sentimental comedy was not the fashion of that day.

"The three sedate musicians in the orchestra, totally engrossed by minims and crotchets, are an admirable contrast to the company in the pit."

The thought on which this whimsical and highly-characteristic print is founded, originated in Calais, to which place Mr. Hogarth, accompanied by some of his friends, made an excursion, in the year 1747.

Extreme partiality for his native country was the leading trait of his character; he seems to have begun his three hours' voyage with a firm determination to be displeased at every thing he saw out of Old England. For a meagre, powdered figure, hung with tatters, a-la-mode de Paris, to affect the airs of a coxcomb, and the importance of a sovereign, is ridiculous enough; but if it makes a man happy, why should[Pg 34] he be laughed at? It must blunt the edge of ridicule, to see natural hilarity defy depression; and a whole nation laugh, sing, and dance, under burthens that would nearly break the firm-knit sinews of a Briton. Such was the picture of France at that period, but it was a picture which our English satirist could not contemplate with common patience. The swarms of grotesque figures who paraded the streets excited his indignation, and drew forth a torrent of coarse abusive ridicule, not much to the honour of his liberality. He compared them to Callot's beggars—Lazarus on the painted cloth—the prodigal son—or any other object descriptive of extreme contempt. Against giving way to these effusions of national spleen in the open street, he was frequently cautioned, but advice had no effect; he treated admonition with scorn, and considered his monitor unworthy the name of Englishman. These satirical ebullitions were at length checked. Ignorant of the customs of France, and considering the gate of Calais merely as a piece of ancient architecture, he began to make a sketch. This was soon observed; he was seized as a spy, who intended to draw a plan of the fortification, and escorted by a file of musqueteers to M. la Commandant. His sketch-book was examined, leaf by leaf, and found to contain drawings that had not the most distant relation to tactics. Notwithstanding this favourable circumstance, the governor, with great politeness, assured him, that had not a treaty between the nations been actually signed, he should have been under the disagreeable necessity of hanging him upon the ramparts: as it was, he must be permitted the privilege of providing him a few military attendants, who should do themselves the honour of waiting upon him, while he resided in the dominions of "the grande monarque." Two sentinels were then ordered to escort him to his hotel, from whence they conducted him to the vessel; nor did they quit their prisoner, until he was a league from shore; when, seizing him by the shoulders, and spinning him round upon the deck, they said he was now at liberty to pursue his voyage without further molestation.

So mortifying an adventure he did not like to hear recited, but has in this print recorded the circumstance which led to it. In one corner he has given a portrait of himself, making the drawing; and to shew the moment of arrest, the hand of a serjeant is upon his shoulder.

The French sentinel is so situated, as to give some idea of a figure hanging in chains: his ragged shirt is trimmed with a pair of paper ruffles. The old woman, and a fish which she is pointing at, have a striking resemblance. The abundance of parsnips, and other vegetables, indicate what are the leading articles in a Lenten feast.

Mr. Pine, the painter, sat for the friar, and from thence acquired the title of Father Pine. This distinction did not flatter him, and he frequently requested that the countenance might be altered, but the artist peremptorily refused.

One of our old writers gives it as his opinion, that "there are onlie two subjects which are worthie the studie of a wise man," i.e. religion and politics. For the first, it does not come under inquiry in this print,—but certain it is, that too sedulously studying the second, has frequently involved its votaries in many most tedious and unprofitable disputes, and been the source of much evil to many well-meaning and honest men. Under this class comes the Quidnunc here pourtrayed; it is said to be intended for a Mr. Tibson, laceman, in the Strand, who paid more attention to the affairs of Europe, than to those of his own shop. He is represented in a style somewhat similar to that in which Schalcken painted William the third,—holding a candle in his right hand, and eagerly inspecting the Gazetteer of the day. Deeply interested in the intelligence it contains, concerning the flames that rage on the Continent, he is totally insensible of domestic danger, and regardless of a flame, which, ascending to his hat,—

From the tie-wig, stockings, high-quartered shoes, and sword, I should suppose it was painted about the year 1730, when street robberies were so frequent in the metropolis, that it was customary for men in trade to wear swords, not to preserve their religion and liberty from foreign invasion, but to defend their own pockets from "domestic collectors."

The original sketch Hogarth presented to his friend Forrest; it was etched by Sherwin, and published in 1775.

The picture from which this print was copied, Hogarth painted by the order of Miss Edwards, a woman of large fortune, who having been laughed at for some singularities in her manners, requested the artist to recriminate on her opponents, and paid him sixty guineas for his production.

It is professedly intended to ridicule the reigning fashions of high life, in the year 1742: to do this, the painter has brought into one group, an old beau and an old lady of the Chesterfield school, a fashionable young lady, a little black boy, and a full-dressed monkey. The old lady, with a most affected air, poises, between her finger and thumb, a small tea-cup, with the beauties of which she appears to be highly enamoured.

The gentleman, gazing with vacant wonder at that and the companion saucer which he holds in his hand, joins in admiration of its astonishing beauties!

This gentleman is said to be intended for Lord Portmore, in the habit he first appeared at Court, on his return from France. The cane dangling from his wrist, large muff, long queue, black stock, feathered chapeau, and shoes, give him the air of

The old lady's habit, formed of stiff brocade, gives her the appearance of a squat pyramid, with a grotesque head at the top of it. The young one is fondling a little black boy, who on his part is playing with a petite pagoda. This miniature Othello has been said to be intended for the late Ignatius Sancho, whose talents and virtues[Pg 38] were an honour to his colour. At the time the picture was painted, he would have been rather older than the figure, but as he was then honoured by the partiality and protection of a noble family, the painter might possibly mean to delineate what his figure had been a few years before.

The little monkey, with a magnifying glass, bag-wig, solitaire, laced hat, and ruffles, is eagerly inspecting a bill of fare, with the following articles pour diner; cocks' combs, ducks' tongues, rabbits' ears, fricasee of snails, grande d'œufs buerre.

In the centre of the room is a capacious china jar; in one corner a tremendous pyramid, composed of packs of cards, and on the floor close to them, a bill, inscribed "Lady Basto, Dr to John Pip, for cards,—£300."

The room is ornamented with several pictures; the principal represents the Medicean Venus, on a pedestal, in stays and high-heeled shoes, and holding before her a hoop petticoat, somewhat larger than a fig-leaf; a Cupid paring down a fat lady to a thin proportion, and another Cupid blowing up a fire to burn a hoop petticoat, muff, bag, queue wig, &c. On the dexter side is another picture, representing Monsieur Desnoyer, operatically habited, dancing in a grand ballet, and surrounded by butterflies, insects evidently of the same genus with this deity of dance. On the sinister, is a drawing of exotics, consisting of queue and bag-wigs, muffs, solitaires, petticoats, French heeled shoes, and other fantastic fripperies.

Beneath this is a lady in a pyramidical habit walking the Park; and as the companion picture, we have a blind man walking the streets.

The fire-screen is adorned with a drawing of a lady in a sedan-chair—

As Hogarth made this design from the ideas of Miss Edwards, it has been said that he had no great partiality for his own performance, and that, as he never would consent to its being engraved, the drawing from which the first print was copied, was made by the connivance of one of her servants. Be that as it may, his ridicule on the absurdities of fashion,—on the folly of collecting old china,—cookery,—card playing, &c. is pointed, and highly wrought.

At the sale of Miss Edwards's effects at Kensington, the original picture was purchased by the father of Mr. Birch, surgeon, of Essex-street, Strand.

The general aim of historical painters, says Mr. Ireland, has been to emblazon some signal exploit of an exalted and distinguished character. To go through a series of actions, and conduct their hero from the cradle to the grave, to give a history upon canvass, and tell a story with the pencil, few of them attempted. Mr. Hogarth saw, with the intuitive eye of genius, that one path to the Temple of Fame was yet untrodden: he took Nature for his guide, and gained the summit. He was the painter of Nature; for he gave, not merely the ground-plan of the countenance, but marked the features with every impulse of the mind. He may be denominated the biographical dramatist of domestic life. Leaving those heroic monarchs who have blazed through their day, with the destructive brilliancy of a comet, to their adulatory historians, he, like Lillo, has taken his scenes from humble life, and rendered them a source of entertainment, instruction, and morality.

This series of prints gives the history of a Prostitute. The story commences with her arrival in London, where, initiated in the school of profligacy, she experiences the miseries consequent to her situation, and dies in the morning of life. Her variety of wretchedness, forms such a picture of the way in which vice rewards her votaries, as ought to warn the young and inexperienced from entering this path of infamy.

The first scene of this domestic tragedy is laid at the Bell Inn, in Wood-street, and the heroine may possibly be daughter to the poor old clergyman who is reading the direction of a letter close to the York waggon, from which vehicle she has just alighted. In attire—neat, plain, unadorned; in demeanor—artless, modest, diffident: in the bloom of youth, and more distinguished by native innocence than elegant symmetry; her conscious blush, and downcast eyes, attract the attention of a female fiend, who panders to the vices of the opulent and libidinous. Coming out of the door of the inn, we discover two men, one of whom is eagerly gloating on the devoted victim. This is a portrait, and said to be a strong resemblance of Colonel Francis Chartres.[Pg 40]

The old procuress, immediately after the girl's alighting from the waggon, addresses her with the familiarity of a friend, rather than the reserve of one who is to be her mistress.

Had her father been versed in even the first rudiments of physiognomy, he would have prevented her engaging with one of so decided an aspect: for this also is the portrait of a woman infamous in her day: but he, good, easy man, unsuspicious as Fielding's parson Adams, is wholly engrossed in the contemplation of a superscription to a letter, addressed to the bishop of the diocese. So important an object prevents his attending to his daughter, or regarding the devastation occasioned by his gaunt and hungry Rozinante having snatched at the straw that packs up some earthenware, and produced

From the inn she is taken to the house of the procuress, divested of her home-spun garb, dressed in the gayest style of the day; and the tender native hue of her complexion incrusted with paint, and disguised by patches. She is then introduced to Colonel Chartres, and by artful flattery and liberal promises, becomes intoxicated with the dreams of imaginary greatness. A short time convinces her of how light a breath these promises were composed. Deserted by her keeper, and terrified by threats of an immediate arrest for the pompous paraphernalia of prostitution, after being a short time protected by one of the tribe of Levi, she is reduced to the hard necessity of wandering the streets, for that precarious subsistence which flows from the drunken rake, or profligate debauchee. Here her situation is truly pitiable! Chilled by nipping frost and midnight dew, the repentant tear trickling on her heaving bosom, she endeavours to drown reflection in draughts of destructive poison. This, added to the contagious company of women of her own description, vitiates her mind, eradicates the native seeds of virtue, destroys that elegant and fascinating simplicity, which gives additional charms to beauty, and leaves, in its place, art, affectation, and impudence.

Neither the painter of a sublime picture, nor the writer of an heroic poem, should introduce any trivial circumstances that are likely to draw the attention from the principal figures. Such compositions should form one great whole: minute detail will inevitably weaken their effect. But in little stories, which record the domestic incidents of familiar life, these accessary accompaniments, though trifling in themselves, acquire a consequence from their situation; they add to the interest, and realise the scene. In this, as in almost all that were delineated by Mr. Hogarth, we see a close regard paid to things as they then were; by which means his prints become a sort of historical record of the manners of the age.

Entered into the path of infamy, the next scene exhibits our young heroine the mistress of a rich Jew, attended by a black boy,[1] and surrounded with the pompous parade of tasteless profusion. Her mind being now as depraved, as her person is decorated, she keeps up the spirit of her character by extravagance and inconstancy. An example of the first is exhibited in the monkey being suffered to drag her rich head-dress round the room, and of the second in the retiring gallant. The Hebrew is represented at breakfast with his mistress; but, having come earlier than was expected, the favourite has not departed. To secure his retreat is an exercise for the invention of both mistress and maid. This is accomplished by the lady finding a pretence for quarrelling with the Jew, kicking down the tea-table, and scalding his legs, which, added to the noise of the china, so far engrosses his attention, that the paramour, assisted by the servant, escapes discovery.

The subjects of two pictures, with which the room is decorated, are David dancing before the ark, and Jonah seated under a gourd. They are placed there, not merely as circumstances which belong to Jewish story, but as a piece of covert ridicule on the old masters, who generally painted from the ideas of others, and repeated the same tale ad infinitum. On the toilet-table we discover a mask, which well enough intimates where she had passed part of the preceding night, and that masquerades, then a very fashionable amusement, were much frequented by women of this description; a sufficient reason for their being avoided by those of an opposite character.

Under the protection of this disciple of Moses she could not remain long. Riches were his only attraction, and though profusely lavished on this unworthy object, her[Pg 42] attachment was not to be obtained, nor could her constancy be secured; repeated acts of infidelity are punished by dismission; and her next situation shows, that like most of the sisterhood, she had lived without apprehension of the sunshine of life being darkened by the passing cloud, and made no provision for the hour of adversity.

In this print the characters are marked with a master's hand. The insolent air of the harlot, the astonishment of the Jew, eagerly grasping at the falling table, the start of the black boy, the cautious trip of the ungartered and barefooted retreating gallant, and the sudden spring of the scalded monkey, are admirably expressed. To represent an object in its descent, has been said to be impossible; the attempt has seldom succeeded; but, in this print, the tea equipage really appears falling to the floor; and, in Rembrandt's Abraham's Offering, in the Houghton collection, now at Petersburg, the knife dropping from the hand of the patriarch, appears in a falling state.

Quin compared Garrick in Othello to the black boy with the tea-kettle, a circumstance that by no means encouraged our Roscius to continue acting the part. Indeed, when his face was obscured, his chief power of expression was lost; and then, and not till then, was he reduced to a level with several other performers. It has been remarked, however, that Garrick said of himself, that when he appeared in Othello, Quin, he supposed, would say, "Here's Pompey! where's the tea-kettle?"

We here see this child of misfortune fallen from her high estate! Her magnificent apartment is quitted for a dreary lodging in the purlieus of Drury-lane; she is at breakfast, and every object exhibits marks of the most wretched penury: her silver tea-kettle is changed for a tin pot, and her highly decorated toilet gives place to an old leaf table, strewed with the relics of the last night's revel, and ornamented with a broken looking-glass. Around the room are scattered tobacco-pipes, gin measures, and pewter pots; emblems of the habits of life into which she is initiated, and the company which she now keeps: this is farther intimated by the wig-box of James Dalton, a notorious street-robber, who was afterwards executed. In her hand she displays a watch, which might be either presented to her, or stolen from her last night's gallant. By the nostrums which ornament the broken window, we see that poverty is not her only evil.

The dreary and comfortless appearance of every object in this wretched receptacle, the bit of butter on a piece of paper, the candle in a bottle, the basin upon a chair, the punch-bowl and comb upon the table, and the tobacco-pipes, &c. strewed upon the unswept floor, give an admirable picture of the style in which this pride of Drury-lane ate her matin meal. The pictures which ornament the room are, Abraham offering up Isaac, and a portrait of the Virgin Mary; Dr. Sacheverell and Macheath the highwayman, are companion prints. There is some whimsicality in placing the two ladies under a canopy, formed by the unnailed valance of the bed, and characteristically crowned by the wig-box of a highwayman.

When Theodore, the unfortunate king of Corsica, was so reduced as to lodge in a garret in Dean-street, Soho, a number of gentlemen made a collection for his relief. The chairman of their committee informed him, by letter, that on the following day, at twelve o'clock, two of the society would wait upon his majesty with the money. To give his attic apartment an appearance of royalty, the poor monarch placed an arm-chair[Pg 44] on his half-testered bed, and seating himself under the scanty canopy, gave what he thought might serve as the representation of a throne. When his two visitors entered the room, he graciously held out his right hand, that they might have the honour of—kissing it!

A magistrate, cautiously entering the room, with his attendant constables, commits her to a house of correction, where our legislators wisely suppose, that being confined to the improving conversation of her associates in vice, must have a powerful tendency towards the reformation of her manners. Sir John Gonson, a justice of peace, very active in the suppression of brothels, is the person represented. In a View of the Town in 1735, by T. Gilbert, fellow of Peterhouse, Cambridge, are the following lines:

Pope has noticed him in his Imitation of Dr. Donne, and Loveling, in a very elegant Latin ode. Thus, between the poets and the painter, the name of this harlot-hunting justice, is transmitted to posterity. He died on the 9th of January, 1765.

The situation, in which the last plate exhibited our wretched female, was sufficiently degrading, but in this, her misery is greatly aggravated. We now see her suffering the chastisement due to her follies; reduced to the wretched alternative of beating hemp, or receiving the correction of a savage task-master. Exposed to the derision of all around, even her own servant, who is well acquainted with the rules of the place, appears little disposed to show any return of gratitude for recent obligations, though even her shoes, which she displays while tying up her garter, seem by their gaudy outside to have been a present from her mistress. The civil discipline of the stern keeper has all the severity of the old school. With the true spirit of tyranny, he sentences those who will not labour to the whipping-post, to a kind of picketing suspension by the wrists, or having a heavy log fastened to their leg. With the last of these punishments he at this moment threatens the heroine of our story, nor is it likely that his obduracy can be softened except by a well applied fee. How dreadful, how mortifying the situation! These accumulated evils might perhaps produce a momentary remorse, but a return to the path of virtue is not so easy as a departure from it.

To show that neither the dread, nor endurance, of the severest punishment, will deter from the perpetration of crimes, a one-eyed female, close to the keeper, is picking a pocket. The torn card may probably be dropped by the well-dressed gamester, who has exchanged the dice-box for the mallet, and whose laced hat is hung up as a companion trophy to the hoop-petticoat.

One of the girls appears scarcely in her teens. To the disgrace of our police, these unfortunate little wanderers are still suffered to take their nocturnal rambles in the most public streets of the metropolis. What heart, so void of sensibility, as not to heave a pitying sigh at their deplorable situation? Vice is not confined to colour, for a black woman is ludicrously exhibited, as suffering the penalty of those frailties, which are imagined peculiar to the fair.[Pg 46]

The figure chalked as dangling upon the wall, with a pipe in his mouth, is intended as a caricatured portrait of Sir John Gonson, and probably the production of some would-be artist, whom the magistrate had committed to Bridewell, as a proper academy for the pursuit of his studies. The inscription upon the pillory, "Better to work than stand thus;" and that on the whipping-post near the laced gambler, "The reward of idleness," are judiciously introduced.

In this print the composition is good: the figures in the back-ground, though properly subordinate, are sufficiently marked; the lassitude of the principal character, well contrasted by the austerity of the rigid overseer. There is a fine climax of female debasement, from the gaudy heroine of our drama, to her maid, and from thence to the still object, who is represented as destroying one of the plagues of Egypt.

Such well dressed females, as our heroine, are rarely met with in our present houses of correction; but her splendid appearance is sufficiently warranted by the following paragraph in the Grub-street Journal of September 14th, 1730.

"One Mary Moffat, a woman of great note in the hundreds of Drury, who, about a fortnight ago, was committed to hard labour in Tothill-fields Bridewell, by nine justices, brought his majesty's writ of habeas corpus, and was carried before the right honourable the Lord Chief Justice Raymond, expecting to have been either bailed or discharged; but her commitment appearing to be legal, his lordship thought fit to remand her back again to her former place of confinement, where she is now beating hemp in a gown very richly laced with silver."

Released from Bridewell, we now see this victim to her own indiscretion breathe her last sad sigh, and expire in all the extremity of penury and wretchedness. The two quacks, whose injudicious treatment, has probably accelerated her death, are vociferously supporting the infallibility of their respective medicines, and each charging the other with having poisoned her. The meagre figure is a portrait of Dr. Misaubin, a foreigner, at that time in considerable practice.

These disputes, it has been affirmed, sometimes happen at a consultation of regular physicians, and a patient has been so unpolite as to die before they could determine on the name of his disorder.