MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY

T. LEMAN HARE

| Artist. |

Author. |

| |

| VELAZQUEZ. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| REYNOLDS. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| TURNER. |

C. Lewis Hind. |

| ROMNEY. |

C. Lewis Hind. |

| GREUZE. |

Alys Eyre Macklin. |

| BOTTICELLI. |

Henry B. Binns. |

| ROSSETTI. |

Lucien Pissarro. |

| BELLINI. |

George Hay. |

| FRA ANGELICO. |

James Mason. |

| REMBRANDT. |

Josef Israels. |

| LEIGHTON. |

A. Lys Baldry. |

| RAPHAEL. |

Paul G. Konody. |

| HOLMAN HUNT. |

Mary E. Coleridge. |

| TITIAN. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| MILLAIS. |

A. Lys Baldry. |

| CARLO DOLCI. |

George Hay. |

| GAINSBOROUGH. |

Max Rothschild. |

| TINTORETTO. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| LUINI. |

James Mason. |

| FRANZ HALS. |

Edgcumbe Staley. |

| VAN DYCK. |

Percy M. Turner. |

| LEONARDO DA VINCI. |

M. W. Brockwell. |

| RUBENS. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| WHISTLER. |

T. Martin Wood. |

| HOLBEIN. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| BURNE-JONES. |

A. Lys Baldry. |

| VIGÉE LE BRUN. |

C. Haldane MacFall. |

| CHARDIN. |

Paul G. Konody. |

| FRAGONARD. |

C. Haldane MacFall. |

| MEMLINC. |

W. H. J. & J. C. Weale. |

| CONSTABLE. |

C. Lewis Hind. |

| RAEBURN. |

James L. Caw. |

| JOHN S. SARGENT. |

T. Martin Wood. |

| LAWRENCE. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| DÜRER. |

H. E. A. Furst. |

| MILLET. |

Percy M. Turner. |

| WATTEAU. |

C. Lewis Hind. |

| HOGARTH. |

C. Lewis Hind. |

| MURILLO. |

S. L. Bensusan. |

| WATTS. |

W. Loftus Hare. |

| INGRES. |

A. J. Finberg. |

| COROT. |

Sidney Allnutt. |

| DELACROIX. |

Paul G. Konody. |

Others in Preparation.

PLATE I.—A GROUP OF ANGELS. (Frontispiece)

This panel from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence is an example of Fra Angelico's most popular work. It is painted in his earliest manner and the figures are stiff and conventional, but the simplicity and beauty that can be found in the group connect it with the paintings of the primitives who were in a sense Angelico's forebears.

Fra ANGELICO

BY JAMES MASON

ILLUSTRATED WITH EIGHT

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK

NEW YORK: FREDERICK A. STOKES CO.

[vii]

[ix]

[11]

I

INTRODUCTION

ROUND the peaceful life and delicately imaginative work of Guido da Vicchio, the Florentine artist who is known to the world at large as Fra Angelico, critics and laymen continue to wage a fierce controversy.[12] While few are heard to deny the merit of the artist's exquisite achievement, it is hard to find, even among those who are interested in early Florentine religion and art, men who can agree about Fra Angelico's positions between the monastery and the studio. "He was a man with a beautiful mind," says one; "a light of the Church, a saint by temperament, and he chanced to be a painter." "You are entirely wrong," says the supporter of the opposing theory; "he was a Heaven-sent artist who chanced to take the vows."

So the schools of art and theology rage furiously together, after the fashion of the two men who approached a statue from opposite sides and quarrelled because one said that the shield carried by the bronze figure was made of gold, and the other said it was made of silver. Incensed by each[14] other's obstinacy they drew swords and fought until they both fell helpless to the ground, only to be assured by a third traveller, who chanced to pass by, that the shield had gold on one side and silver on the other.

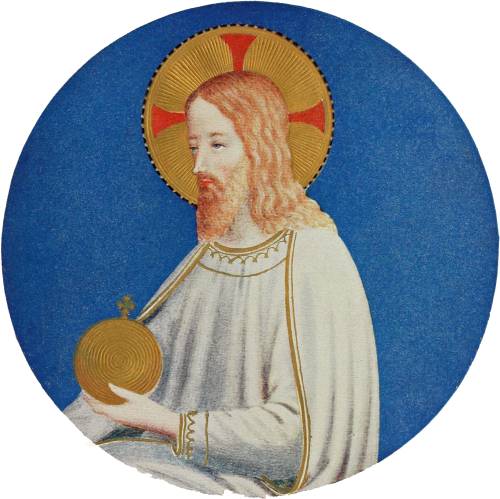

PLATE II.—A FIGURE OF CHRIST

Detail from San Marco's Convent in Florence. This striking example of the master's mature art reveals in most favourable light his exquisite conception of Christ. Although this is no more than part of a picture, it has been reproduced here in order that the details of the handling may be appreciated.

Standing well apart from the enthusiasts of both sides, the average man sees that Fra Angelico was an artist of remarkable attainments and at the same time a devout, God-fearing friar, who seems to have deserved a great part at least of the praise he received from the honeyed pen of Giorgio Vasari. Naturally enough the modern artist finds in Fra Angelico, or "Beato" Angelico as he is sometimes called, one of the most interesting painters of the fifteenth century, and he does not bother about the fact that his hero chanced to be a Dominican brother. Very devout Catholics, on the other hand,[16] will approach Fra Angelico's work on the literary side, and will be profoundly conscious of the fact that he was the first great artist of Italy who, realising the maternity of the Madonna, represented her as a mother full of human affection, and the Holy Child as a beautiful baby boy. It is the painter's abiding claim to our regard that he brought life to his walls and panels, that they present the living, palpitating sentiment of men and women and children, that he painted for us the flowers that blossomed round him and the countryside through which he wandered in his hours of ease. The technical achievement, the gradual but steady improvement in dealing with composition and masses of colour, the extraordinary change from the stiff early figures to the supple ones of the later years, the splendid growth of the artistic sense, from all these things the[17] devotee turns aside. He is not unconscious of the change, for the results achieved by the painter account for the spectator's riper and fuller appreciation, but he cannot analyse it. Of far more moment to him is the thought that all Fra Angelico's life and art were given to the service of the Church, that he laboured without ceasing to present the Gospel stories in the most attractive form, despising the material rewards that awaited such achievements as his. Ease, luxury and the praise of the world at large the Dominican dismissed with fine indifference, believing that his reward would come when his task was ended, and the work of his hands should praise him in the gates. "Here," his orthodox latter-day admirers say, "is the man of noble convictions and pure life, who stood for all that was best in religion. As he chanced to have the[18] gifts of a painter, he used those gifts to develop his mission. Painting with him was no more than a means to an end, and that end was the glorification of God." The dispute must needs be endless; for we cannot see through the four centuries that separate us from the artist, and every man takes from a picture some echo of what he brought to it.

In sober truth the matter is of far less importance than the makers of controversy imagine. It should suffice both parties to agree that Fra Angelico was a great painter and a great man, that his association with the Church afforded him the opportunity of leaving behind him work that has a spiritual as well as artistic quality. His altar-pieces and frescoes seem to breathe the serene atmosphere of an age of faith; they tell of a quiet retired life amid surroundings that[19] remain unrivalled to-day, even though our horizon is widened and we know the New World as well as the Old.

There are examples of the painter's art in the National Gallery and in the Louvre, in Rome and in Perugia; but Florence holds by far the greatest number. In Florence we find the series painted to decorate the "Silver Press" of the Annunziata, and more than a dozen other works of importance. The Uffizi guards the famous "Madonna dei Linajuoli" and the "Coronation of the Virgin" from Santa Maria Nuova. The Convent of San Marco, to which the Brotherhood of San Dominico went in 1346 from Fiesole, holds the famous frescoes in cloister, chapter-house, and cells, and offers an illuminating guide to the painter's ideals and intentions, in work that is the ripe product of middle age. So it is to Florence that one[20] must go to study the painter, though there are one or two works from his hands in Fiesole across the valley, while the collection in Perugia is not to be overlooked, and Rome holds some of the best work of the artist's hand, painted in the closing years. For all the surging waves of tourists that break upon Florence, month in, month out, filling streets and galleries with discordant noises, and giving them an air of unrest strangely out of keeping with their traditional aspect, the city preserves sufficient of its old-time character to enable the student to study Fra Angelico's pictures in an atmosphere that would not have been altogether repugnant to the artist himself. Save in seasons when the city is full to overflowing the Convent of San Marco receives few visitors, while in the Academy and at the Uffizi there are so many expressions of a more flamboyant art[21] that there is seldom any lack of space round the panels Angelico painted.

There are some days when San Marco is altogether free from visitors, and then the frescoed cells, through which the great white glare of the day steals softly and subdued, seem to be waiting for the devotees who will return no more, and one looks anxiously to cloisters, and garden and chapter-house for some signs of the life that rose so far above the varied emptiness of our own.

II

THE PAINTER'S EARLY DAYS

When Guido da Vicchio was born in the little fortified town from which he takes his name, the town that looks out upon the Apennines on the North and West, and towards Monte Giovo on the South, the[22] Medici family was just beginning to raise its head in Florence. Salvestro di Medici had originated the "Tumult of the Ciompi"; the era of democratic government in the city was drawing to a close. Beyond the boundaries of Florence the various states into which Italy was divided were quarrelling violently among themselves. The throne of St. Peter was rent by schism, Pope and anti-Pope were striving one against the other in fashion that was amazing and calculated to bring the Papal power into permanent disrepute. It was a period of uncertainty and unrest, prolific in saints and sinners, voluptuaries and ascetics. No student of history will need to be reminded that it is to periods such as this that the world has learned to look for its remarkable men.

PLATE III.—TWO ANGELS WITH TRUMPETS

These panels from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence are very popular examples of the master's early work, and although they do not compare favourably with his later efforts, they have achieved an extraordinary measure of popularity in Italy, and are to be seen on picture postcards in every Italian city from Genoa to Naples. (See p. 32.)

Doubtless some echo of the surrounding[24] strife penetrated beyond the walls of Vicchio when Guido was a little boy, for he lived in a fortified town built for purposes of war. It is not unreasonable to suppose that he may have seen enough of the stress and strife peculiar to the age to have turned his thoughts to other things. If a lad, born with a peaceable and affectionate disposition, be brought into contact with violence at an early age, his peaceful tendencies will be strengthened, he will avoid all sources and scenes of strife. We know nothing of the painter's boyhood, but, looking round at the conditions prevailing in Florence, it seems more than likely that the years were not quite restful.

In the absence of authentic information one may do no more than suggest that, when the lad was newly in his teens, he served in the studio of some local painter[26] and discovered his own talent. Attempts have been made to give the teacher a name and a history, but these efforts, for all that they are interesting, lack authenticity. Far away in Florence the first faint light of the Revival of Learning was shining upon the more intelligent partisans of all the jarring factions. The claims of the religious life were being put forward with extraordinary fervour and ability by a great teacher and preacher, John the Dominican, who appears to have reformed the somewhat lax rules of his order. We are told that he travelled on foot from town to town after the fashion of his time, calling upon sinners to repent, and summoning to join the brotherhood all those who regarded life as a dangerous and uncertain road to a greater and nobler future. Clerics looked askance at the signs of the times, for although art and literature were[27] coming into favour, although Florence was becoming the centre of a great humanist movement, the change was associated with a recrudescence of pagan luxury and vices that boded ill for the maintenance of moral law.

Perhaps John the Dominican preached in Vicchio, perhaps Guido and his younger brother Benedetto heard him elsewhere, but wherever the message was delivered it went home, for it is recorded that in the year 1407, when Fra Angelico would have been just twenty years old, he and Benedetto travelled to the Dominican Convent on the hillside at Fiesole and applied for admission to the order. The brothers were welcomed and sent to serve their novitiate at Cortona, where some of Fra Angelico's earliest known work was painted. They returned to Fiesole in the following year,[28] but the Dominican establishment there was soon broken up because the Florentines had acknowledged Alexander V. as Pope, and the Dominican Brotherhood supported his opponent, Gregory XI. Foligno and Cortona were visited in turn. In the former city the Church of the Dominicans remains to-day; and so the brethren sought peace beyond Fiesole, until in 1418 the Council of Constance healed the wounds of Mother Church. Then Pope Martin V. came to live in Florence, where John XXIII. paid him obeisance, and the Dominican friars returned to their hillside home beyond the city, that was then, according to the historian Bisticci, "in a most blissful state, abounding in excellent men in every faculty, and full of admirable citizens."

And now Fra Angelico, as he must be called in future, settled down to his first[29] important work. He had learned as much as his associates could teach him, and had gathered sufficient strength of purpose, intelligence and judgment, to enable him to deal with the problems of his art as he thought best. It may be said that Fra Angelico built the bridge by which mediæval art travelled into the country of the Renaissance. Indeed, he did more than this, for having built the bridge, he boldly passed over it in the last years of his life. We can see in his work the unmistakable marks of the years of his labour. He started out equipped with the heavy burden of all the conventions of mediævalism. Against that drawback he could set independence of thought, and a goodly measure of that Florentine restlessness that led men to express themselves in every art-form known to the world. No Florentine artist of the Quattrocento held[30] that painting was enough if he could add sculpture to it, or that sculpture would serve if architecture could be added to that. Had there been any other form of art-expression to their hands, the Florentines would have used it, because they were as men who seek to speak in many languages. This restlessness, this prodigality of effort, was to find its final expression in Leonardo da Vinci, who entered the world as the Dominican friar was leaving it.

In the early days Fra Angelico must have been a miniaturist. Vasari speaks of him as being pre-eminent as painter, miniaturist, and religious man, and the painting of miniatures cramped the painter's style in fashion that detracts from the merits of the earlier pictures, but of course Fra Angelico is by no means the only artist to whom miniature painting has been a pitfall.

[31] Professor Langton Douglas has pointed out, in his admirable and exhaustive work on Fra Angelico, that the artist was profoundly influenced by the great painters and architects of his time, and has even used this undisputed fact as an aid to ascertain the approximate date of certain pictures. We can hardly wonder that the influence should be felt by a sensitive artist, who responded readily to outside forces, when we consider the quality of the work that sculpture and architecture were giving to the world in those early days of the Quattrocento. Men of genius dominated every path in life and Florence held far more than a fair share of them.

Among the works belonging to the years before Fra Angelico went to San Marco, and painted the frescoes that stand for his middle period at its best, are the Altar-piece[32] at Cortona, "The Annunciation" and "The Last Judgment," in the Academy of Florence, and the famous "Madonna da Linajuoli," with its twelve angels playing divers musical instruments on the frame round the central panel. These angels have made the Madonna of the Flax-workers the best known of all the painter's works. So long the delight of the public eye they are very harshly criticised to-day, and not without reason, for doubtless they are flat and stiff productions enough. But they have a certain naïve beauty of their own, and because they have done more than work of far greater merit to spread the fame of Fra Angelico, because they have been the source of great delight to countless people despised and rejected of art critics, it has seemed reasonable to present some of them in this little volume, side by side with those more[34] important works of the master to which so many artists of the Renaissance are indebted. We may rest assured that to the painter the angels were very real angels indeed, the best that his art and devotion could express.

PLATE IV.—CHRIST AS A PILGRIM MET BY TWO DOMINICANS

This is a fresco in the cloister of San Marco at Florence. It will be seen that Christ holds a pilgrim's staff which cuts the picture in half, and the right hand of the foremost Dominican and the left hand of Christ, extended across the staff, form a cross.

Other important works of this first period, which may be taken to range from 1407 to 1435, are the altar-pieces known as the Madonna of Cortona, the Madonna of Perugia, and the Madonna of the Annelena, the last-named being in the Academy at Florence. Critics and artists can divide the painter's life into four or more divisions expressed to them by changes in his style; but a simpler division suffices here.

Looking at Fra Angelico with eyes that the nineteenth century has trained, we speak of this early work as of less importance than what followed, but in so doing it is[36] quite easy to speak or write as several of his critics have done in very unreasonable fashion. Certainly the artist, who in the last years of his life painted the picture of St. Lorenzo distributing alms, and the scenes in the life of St. Stephen, has travelled very far from the painter of the "Last Judgment" that may be seen in Florence; but, even in the early days of Cortona, Fra Angelico was a modern of the moderns. He was a man who worked and thought far in advance of his times, who had the wide outlook that we have learned to associate with all the Florentine artists of the Quattrocento, and he left the boundaries of the painter's art far wider than he found them. Doubtless many of his contemporaries found his work daring and even immoral in so far as it departed from the traditions that had satisfied his predecessors. He had an[37] individuality that expressed itself in fashion unmistakable before he was thirty years of age, and developed steadily down to the last year of his life. Divorced by his calling from the cares and joys of other men, he responded with delight to the larger and more general aspects of life. Fra Angelico had a keen and eager eye for natural beauty; he seems to have gone to the countryside for all the inspiration that remained to seek when the sacred writings were laid aside. The maternal aspect with which he endowed the Madonna, who had hitherto been as stiff and formless as though carved out of wood, testifies to the artist's recognition of maternity as he saw it among the simple peasants his order served. He restored humanity to Mother and Child. The child-like Christ, no longer a doll but a real bambino, tells us how deeply the painter entered into the[38] spirit of a life that the rules of his order forbade him to share. Just as some women who do not marry seem to keep for the world at large the measure of loving sympathy that would have been concentrated upon their children; so this painter monk, who had paid his vows to poverty, chastity, and obedience, could express upon his canvas the affection and the sentiment that would have been bestowed under other circumstances upon a chosen helpmate. Lacking the joys of healthy domesticity he turned to Nature with a loving eye and an intelligence that cannot be over-estimated and, if he knew hours wherein, manlike, he mourned for the life forbidden, the consolation was at hand. The Earth Mother consoled him. In his earliest canvases he expresses his love of flowers, the love of a child for the sights that make the earliest appeal to our[40] sense of beauty. His angels are set in flowering fields, they carry blossoms that bloom in the fields beyond Cortona, and upon the hillside of Fiesole. Clearly the painter saw Paradise around him. Roses and pinks seem to be his favourite flowers, he paints them with a loving care, knowing them in bud and in full leaf and, just as he went to Nature for the decorative side of his art, so in a way he may be said to have gone to Nature in her brightest and most joyous moods for his colours. His palette seems to have borrowed its glory from the rainbow—the gold, the green, the blue, and the red are surely as bright and clear in his pictures as they are in the great and gleaming arch that Easterns call in their own picturesque fashion "The Bride of the Rain."

PLATE V.—THE CORONATION OF THE VIRGIN

This is a detail of a famous picture in San Marco. It is a fresco in a cell of the South Corridor. Christ is seen crowning the Virgin, the clouds surrounding them are rainbow tinted, and below the rainbow six saints are ranged in a semi-circle.

In all his work Fra Angelico showed himself an innovator, a man who, in thinking[42] for himself, would not allow his own clear vision to be obscured by the conventions that bound men of smaller mentality and less significant achievement. At the same time he was very observant of the progress of his peers, particularly in architecture, and students of this branch of art cannot fail to notice his response to the developments brought about by Michelozzo and Brunelleschi. Even in the first period of his art he would have seemed a daring innovator to his contemporaries for, all unconsciously he was taking his share in shaping the great Renaissance movement that left so many timid souls outside the radius of its illumination.

In the early days he approached the human body with some diffidence, and though a greater courage in this regard is the keynote of Renaissance painting, the[43] earlier timidity is hardly to be wondered at when we consider the attitude of the religious houses towards humanity in its physical aspect, and how necessary it was to avoid anything approaching sensuous imagery throughout that anxious period of transition. As he grew older and more confident of his powers, Fra Angelico seems to have freed himself from some of the restrictions that beset an artist who is also a religious. He, too, learned to glorify the human form.

His love for Nature remained constant throughout all the years of his life; he was sufficiently daring to introduce real landscape into his pictures, and by so doing, to become one of the fathers of landscape painting. His angels have a setting in the Italy he knew best, the flowers that strew their paths are those he may have gathered[44] in the convent garden; for even his vivid and exalted imagination could not create aught more beautiful than those that grew so freely and wild by the wayside, or were tended by his brethren in San Marco.

We find throughout the pictures a suggestion that the life of the artist was a serene and tranquil one that, while he was actively concerned with things of art throughout the district he knew best, he was sheltered by the house of the brotherhood from the tumult and turmoil that beset Fiesole, Cortona, and Foligno in the days of his youth. When he went to San Marco in Florence, where his most enduring memorial remains to this day, Fra Angelico was a man of experience and an independence so far in advance of his time, that some of the work he had accomplished comes to us to-day with a suggestion of absolute[45] modernity in thought if not in treatment. No beauty that our more sophisticated age can reveal to us had passed him by, he paints Nature as Milton painted it when he wrote the "Masque of Comus" and "l'Allegro." And this manner of painting, so different from that of men who mix themselves with the world and surrender to its fascinations, is the painting that endures.

III

IN SAN MARCO

It was in 1435, and Fra Angelico was approaching his fiftieth year, when the brotherhood of San Dominico quitted their convent in Fiesole and went to find a new home in Florence. With the turn of the year they left a temporary resting-place in San Giorgio Oltr' Arno and went into the[46] ruined monastery of San Marco. This house appears to have belonged to the brotherhood of San Silvestro whose behaviour had been quite fitted to the fifteenth century in Florence, but was not altogether creditable to a religious house. Pope Eugenius IV., anxious to purify all the religious houses, gave San Marco to the Dominicans with the consent of Cosimo di Medici, and a very poor gift it was at the time, for the dormitory had been destroyed by fire, and hastily-made wooden cabins could not keep out the rain and cold wind. There was a great mortality among the brethren. Once again the Pope Eugenius interceded with the powerful ruler of Florence, and Cosimo sent for his well-beloved architect Michelozzo and commissioned him to rebuild the monastery. Naturally enough Fra Angelico, whose feeling for architecture was finely developed,[47] came under the influence of the architect, and when the building was complete he was commissioned to adorn the walls with frescoes that should keep before the brethren the actualities of the religious life, and enable them to feel that the Spiritual Presence was in their midst.

Cosimo's munificence had not stopped with the presentation of the building to the brotherhood. He equipped the monastery with a famous library, provided all the service books that were necessary, and gave the brethren for librarian a man who was destined to ascend the Fisherman's Throne and keep the keys of Heaven. The books were illuminated by Fra Angelico's brother Benedetto, who had taken the vows with him, indeed some critics are of opinion that Fra Angelico himself assisted in the work, but for[48] this belief there appears to be but a very small foundation.

The Pope Eugenius, compelled by the quarrels of the great houses in Rome to leave the Eternal City, came to Florence and saw Fra Angelico's work there, and this visit paved the way for the painter's sojourn in Rome in the last years of his life. Like so many of his contemporaries, Eugenius could find time amid the distractions of a stormy and difficult existence to keep a well-trained eye upon the artistic developments going on around him, and he did but wait for peace and opportunity to show himself as keen a patron of art as that "terrible pontiff," Julius della Rovere, for whom Michelangelo was to work in the Sistine Chapel.

PLATE VI.—DETAIL FROM THE CORONATION OF THE VIRGIN

This is a detail from one of the pictures that have excited a great deal of criticism. Professor Douglas calls the work "the last and greatest of Fra Angelico's glorified miniatures." In the work as it stands in the Uffizi to-day, Christ is seen placing a jewel in the Virgin's crown. Right and left stretches the Angelic choir, below there is a great gathering of saints.

To realise the life that the painter saw around him in the days when the Dominican[50] brotherhood first went to San Marco, it is necessary to turn to some historian of Florence in an endeavour to recall the splendour and stateliness of the city's life. The limits of space forbid any attempt, however modest, to picture Florence in detail as it was in those days, though the subject could scarcely be more tempting to the pen. The pomp and circumstance of life were not passed over by the painter, whose extraordinary receptivity found so much more in Florence than in Fiesole for its exercise. Some echo, however, subdued to convent walls, lingers in the city to-day where San Marco preserves its great painter's reputation, and tells us that he was not indifferent to the sights and sounds beyond its gates.

A few of the frescoes have lost a little of their pristine beauty and yet, for all the[52] ravages of time, the most faded among them can suggest much of the charm they possessed when they were painted. It is in the open cloisters, of course, that the greatest damage has been done, and the great "Crucifixion" in the chapter-house has not escaped lightly; but in the cells where the work is more protected, time has dealt lightly with the frescoes and the two or three little panels that help to make the friar's lasting monument. Good judges have pointed out that the great "Crucifixion" in the chapter-house, the largest work of the painter, was never completed, and that the red background was intended to serve as a bed for the blue that was never put on. Nobody can say why this fine work was abandoned, and reproduction in colour is impossible. Even a detail would be unsatisfactory, but one of the lunettes from the[53] cloister is given here. It represents Christ as a pilgrim meeting two Dominican brothers, and gives an excellent suggestion of Fra Angelico at his best, revealing the deep feeling of the religious man, and the skill of the artist blended together in happiest and most inspired union. To have seen the picture in his mind, the artist must have been a deeply religious man; to have expressed the vision as he has expressed it in terms of line and colour, the devotee must have been a great artist.

From one of the cells in San Marco the chief part of another picture has been reproduced in these pages. It represents the "Coronation of the Virgin." Christ seated upon a white cloud is placing a crown upon the Virgin's head; there is a rainbow border with six saints. In order that the beauty of the central figures may be seen, no more[54] than a part of the picture is given here. It is the more important part, for the saints are conventional figures, each with the hands uplifted in adoration, each with a halo round his head. The beauty of the stories that Fra Angelico sets before us was as true to him as the beauty of the flowers he painted, and the landscape that met his eyes whenever he walked abroad. The modern world, whether it doubt or believe, cannot but recognise that the artist of San Marco has succeeded as much by his faith as by his art. The other frescoes of the Dominican House must be left for the fortunate minority who can visit them, but these two will be found to represent well and truthfully both the religious idea and the artistic achievement. To realise their merits to the full one must not fail to bear in mind the development of painting at the time when[55] they were painted. For the men who came after Angelico the task was easier; he had paved the way for them. In the days when San Marco was decorated, the painter had very little to add to his technical knowledge, and nothing at all to his feeling for the beauty of the Gospel stories, and few artists of the fifteenth century have been so fortunate as to collect their best work in one place where it could remain undisturbed throughout the ages.

Naturally enough it must pass—cloisters and chapter-house show signs of the times all too clearly. "The Crucifixion" is faded not so badly as Leonardo's "Last Supper" in the Santa Maria della Grazie of Milan, but still seriously, nor can all the lire of faithful but hurried tourists restore its charm. It is in the cells that the work of Fra Angelico will linger longest, and it is pleasant to speculate[56] upon the debt that devout monks must have owed to their artist brother, who could give them such exquisite embodiments of the truth as he saw it to brighten their hard lives and assure them, even in hours of doubt and mental trouble, of the joys that would be associated with the latter end.

San Marco, then, may be regarded as an exquisite and enduring memorial of the middle period of Fra Angelico's life. The saint that was in him dreamed dreams and saw visions, the artist that was in him expressed them in fashion that calls for admiration even in these days when the work done is nearly four hundred years old, and the thought that gave it birth is no longer held in such universal esteem. The devotion that inspired the themes, the simplicity of his handling, the beauty of his colour, the love of Nature that was[57] expressed as often as the picture would permit, the reverential feeling in treatment that was bound to communicate itself to the spectator, all these qualities make the work remarkable, and help us to see how strong was the faith that inspired and kept the artist happy in the cloisters when, had he wished to turn his talent to other purposes, he might have had riches and honour. Leading rulers of men were building palaces in every great city, conquerors and statesmen were seeking to excel one another in tasteful and costly display. Of those who could have commanded wealth, honour, and comfort, the Dominican friar was among the first. But it sufficed Fra Angelico to serve neither kings nor princes, but to choose for his worship the King of kings "Who made the heavens and the earth and all that is therein."

[58]

IV

LATER YEARS

There is a great temptation to linger awhile in San Marco with the friar, for even to-day the place has not lost its appeal, and there are sufficient landmarks in the surrounding city to enable us to trace the influence of men who were at once the contemporaries and inspirers of his genius. Only the limits of space intervene to forbid too long a stay in Florence, and as the painter's later years were spent in Rome we must follow him there. For those who wish to linger in the monastery there are books in plenty, some dealing with the Quattrocento, others dealing with the Popes, others with Fra Angelico himself. This outline of a painter's life seeks to do no more than introduce him to those who may[60] be interested; it is not intended for those who wish to follow him beyond the limits of a modest appreciation. Vasari, Crowe, and Cavalcaselle, Professor Langton Douglas, Bernhard Berenson and others will supply the more complete and detailed accounts of the painter's life and works, and the careful reader will find sufficient references to other writers to direct him to every side issue.

PLATE VII.—THE INFANT CHRIST

From the Convent of San Marco. This picture gives a fair idea of the exquisite sweetness and delicacy with which the painter handled the subject of the child Christ. He does not treat this subject very often, but when he does the result is in every way delightful.

Pope Eugenius IV., who visited Florence when he was exiled from Rome, had settled for a while in Bologna until the anti-Pope Felix V. fell from power, and had then hastened back to Rome, and settled down to beautify the Vatican. Like all the great men of his generation he felt the spirit of the Renaissance in the air, and desired no more than leisure in order to respond to it. He remembered the clever[62] artist, whose work had charmed him in the days of his Florentine exile, and sent an invitation to Fra Angelico to come to Rome and decorate one of the chapels in the Vatican. In those days one travelled in Italy, even more slowly than one does to-day by the Italian express trains—strange as the statement may seem to moderns who know the country well—and by the time that the friar had received the summons and had responded to it, Eugenius IV. would appear to have relinquished the keys to his successor. Happily the new Pope Nicholas V. was a scholar, a gentleman, and a statesman, as responsive to the new ideas as his predecessor in office. He gathered the best men of his time to the Vatican, which he proposed to rebuild, and he entered upon a programme that could scarcely have been carried out had he[63] enjoyed a much longer lease of life than Providence granted. Unfortunately he had no more than eight years to rule at St. Peter's, and that did not serve for much more than a beginning of his great scheme. He was succeeded by Tomaso Parentucelli, that ardent scholar whom Cosimo di Medici had appointed custodian of the collection of MSS. that he gave to San Marco in Florence when the Dominicans took possession. As it happened Parentucelli himself was in the last year of his life when he ascended the throne of St. Peter, and his schemes, whether for the aid and development of scholarship or art, saw no fruition. But for all that Nicholas V. ruled for no more than eight years in Rome, he did much for Fra Angelico, who painted the frescoes in the Pope's private studio, and decorated a chapel in St. Peter's that was[64] afterwards destroyed. This loss is of course a very serious one, and suggests that those who ruled in the Vatican were not always as careful as they might have been of works that would have outlived them so long had they been fairly treated. It is very unfortunate that art should suffer from the caprices of the unintelligent. When Savonarola, also a Dominican monk, roused the Florentines to a sense of their lapses from grace a few years after Fra Angelico's death, they made a bonfire in the streets of Florence of art work that was considered immoral. To sacrifice great work in the name of morality is bad enough, to destroy it for the sake of building operations is quite unpardonable.

In Rome the summer heat is well-nigh unbearable. Even to-day the voluntary prisoner of the Vatican retires to a villa in the[65] far end of his gardens towards the end of June, and none who can leave the city cares to remain in it when May has gone, and the Tiber becomes a thread, and fever haunts its banks. Fra Angelico felt the burden of the summer and wished to suspend his work for a while. It so happened that he received an invitation from Orvieto to decorate the Duomo there during the months of June, July, and August. The first arrangement was that he should go there every summer to escape the dog-days in Rome, but for reasons not known to us the visit did not extend beyond one year, and the frescoes that he had painted were seriously injured by rain, and were not completed until Luca Signorelli took them in hand half a century later. The little work that is attributed to the painter's brush to-day in Orvieto need not detain us here.

[66] The frescoes in Rome represent the summit of Fra Angelico's achievement, but they have not escaped the somewhat destructive hand of nineteenth-century German criticism; one eminent authority having declared that they are not by Fra Angelico at all, but have been painted by pupils, Benozzo Gozzoli receiving special mention in this connection. It is not necessary to take this criticism too seriously. The hands may be the hands of Esau, but "the voice is Jacob's voice." The artist may have received some assistance from pupils, the backgrounds may owe something to another hand; there was no feeling, ethical or artistic, to keep assistants from coming to the aid of their master, but the whole composition and the whole feeling of the frescoes proclaim the friar. The subjects are incidents in the life of St. Stephen and St. Lorenzo,[67] ending, of course, after the inevitable fashion of the time, with a representation of the martyrdom. For once these martyrdoms have a suggestion of reality. In the early days of Fra Angelico's work his representations of martyrdoms and suffering were so naïve that they could hardly do more than provoke a smile. His idea of hell was very simple, and when he wished to be very bitter indeed—to express his anger at its fullest—he peopled the nether world with brothers of the great rival order of St. Francis. For the founder of that order, Angelico had the greatest love and admiration; who indeed could refuse to pay such tribute even to-day? But all the brethren did not live up to the rule of their founder, and the Dominican painter's rebuke seems very quaint in our eyes, though doubtless it made a great sensation when it was administered.

[68]

PLATE VIII.—ST. PETER THE MARTYR

This is a fresco from the Cloisters of San Marco and represents St. Peter, a saint whose appeal to the artist was very great The fact that the saint has his finger to his lips may be taken as the artist's method of emphasising the rule of silence of his Order. In fact the St. Peter Martyr is generally called the "Silenzio," and like so many of the artist's pictures must be taken to have a special spiritual significance.

In Rome the painter's feeling for natural beauty reaches the height of its expression, indeed one feels that every department of his work is at its best and highest there. After his departure from the Eternal City, the frescoes finished, and himself on the shady side of his sixtieth year, the intervening centuries descend like a cloud, blotting out the greater part of the record. The cloud lifts for a moment to show us "Beato" Angelico, Prior of the Dominican Monastery at Fiesole, to which more than forty years ago he had claimed admission as a novice, and then he is back again in Rome in the chief convent of his order, Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. There the light that had burned so brilliantly for nearly half a century, illuminating the most alluring aspects of the Christian faith, paled and went out. The body was laid to rest in the convent[70] Church, near the tomb of St. Catherine, and it is said that the epitaph was composed by the Pope. Thereafter the order of St. Dominic produced no great personality until it gave to the world a man of very different stamp in Fra Girolamo Savonarola.

V

A RETROSPECT

In art as in music and literature the path of the innovator is beset by difficulties, and if, among all the movements that claim our attention to-day, that of the Renaissance in fifteenth-century Italy is the most fascinating, it is because the difficulties were conquered so brilliantly. The century seemed to breed a race of men that enjoyed the inestimable advantage of knowing what they wanted, and were determined to succeed.[72] It did not matter that the paths they trod were new. Each man had mapped out a line of development for himself and went strenuously along his chosen road, quite certain that he would find the goal of his ambition at the journey's end. Curiously enough when the paths were those of conquest there was always a road leading from them to patronage of the arts. This may be because art in those days was largely devoted to the service of the Church, and when a man had acquired all that theft or conquest could give him, and realised that he could not hope to wage successful war upon time, he began to think of his latter days. Few men of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries could approach death with confidence, and they sought to put something to their credit against the Day of Judgment. To beautify religious houses,[73] to build houses for Holy Brotherhoods, these were the simplest and most obvious ways of placating the Recording Angel, and to the uneasiness of rich and unscrupulous men the Church owes not a few of her most remarkable monuments. Moreover, even the tyrants wished to have some enduring memorial. Cosimo di Medici, who gave San Lorenzo and San Marco to Florence, remarked to his historian Bisticci, "Fifty years will not pass before we are driven out of Florence, but these buildings will remain." After all we can forget and forgive the superstition and self-glorification that gave so much enduring wealth to the great cities of Italy.

Doubtless there were many failures among the Renaissance artists; it is hardly an exaggeration to say that in painting alone there are scores of men belonging to[74] the Quattrocento who have left us nothing but their names. Victory was to the fittest; they alone survived and left the impress of their genius upon their own and succeeding generations. If we look for a moment to Fra Angelico's contemporaries we see at once that it was an age of great men. Filippo Brunelleschi was born ten years before Angelico, and lived until the year 1446. He designed the dome of the Cathedral of Florence, the Cloisters of San Lorenzo, the Sagrestia Vecchia, the Church of St. Lawrence, and other works too numerous to mention. Donatello, whose work to this hour is "all a wonder and a great desire;" Ghiberti, to whom Florence owes the gates of the Baptistery; Michelozzo, who built the Medici Palace and the Convent of San Marco, and was associated with Luca della Robbia in making the bronze gates of the Sacristy[75] of the Duomo, belong to the same period, and were intimately associated with Brunelleschi in much of the work that makes Florence one of the show-places of the world to-day. Luca della Robbia was born when Fra Angelico was no more than twelve years old. Masolino, Masaccio, and Fra Filippo Lippi were among the painters of Fra Angelico's own time, while, when he was approaching middle age, Gian Bellini and Andrea Mantegna were growing up, and when Fra Angelico died, Florence was full of great artists who were destined to carry on his work. Of course, the literary activity was as great as the activity of the artists; one recalls with a thrill of emotion that Petrarch and Boccaccio were only just numbered among the dead—their work held all its earliest freshness. If at first sight these matters seem to be outside the scope[76] of a brief consideration of Fra Angelico's life and work, second thought will justify the inclusion even in these narrow limits.

Every artist is in a sense an echo of his environment and, although Fra Angelico must have passed the greater part of his life within monastery walls, yet the evidence of his pictures must convince all who look with discerning eyes, that he was profoundly influenced by the life that went on around him. The artistic and literary movements of the time affected him deeply and, in his own modest way he was constantly striving to enlarge the boundaries of his art, to develop its achievements in a manner that must have made even his early pictures appear as dangerous as the works of artists like Manet and Degas seemed to their contemporaries. Had he lived in other times,[77] had his lines been cast in some quiet city to which no echo of the new movement in art and letters could penetrate, Fra Angelico might still have painted interesting pictures; but he would not have got beyond his earliest manner, indeed he might not have attained to what is best in that. It would have been so very easy for a narrow-minded superior to say that the innovations were wrong, that the human figure in all its beauty must not be expressed by a painter when presenting Virgin and Child, that the old formal way was the right one. There could have been no appeal against such a judgment. Doubtless many a budding genius has been nipped in this fashion by short-sighted authority. How happy then was the friar with time and place united in his service.

[78]

VI

CONCLUSION

Fra Angelico has placed artists and laymen in his debt, and as far as the latter are concerned the cause is obvious enough. A certain conviction of the truth of every story he had to tell shines like a bright light through all his pictures; they are a force for the development and strengthening of belief. Even to-day one finds among the crowd of tourists that "does" San Marco in half-an-hour or more, a few visitors whose interest is of another kind, while there is no lack of admirers for the work to be seen in the Uffizi, though much of it belongs to the earliest part of the artist's life. So it happens that the pictures have a well-defined literary and spiritual[79] value, and it is not surprising to think that the Church has granted posthumous honours to the man whose work has brought so much honour in its train. Artists acknowledge a great debt to the friar, but a debt of another kind. As Professor Langton Douglas has pointed out in his admirable and exhaustive work upon Fra Angelico, the friar, with his contemporaries, Hubert and Jan Van Eyck, are the fathers of modern landscape. The new movement was continued and developed by Verrocchio and Da Vinci on the one side, and by Perugino and Raphael on the other. Then again Fra Angelico made a definite movement towards portrait painting, by giving the likeness of some of his friends and patrons to saints and martyrs. This was yet another of the daring innovations that marked the opening of the Quattrocento[80] and, to realise how much it stood for we must consider for a moment the comparative barrenness of modern art, which in the hands of its most popular artists has little or nothing that is new to say to us. Indeed it may be remarked with regret that great praise often attaches to the man who goes back to the fifteenth and sixteenth century, although a little reflection would enable every thoughtful person to see that an art, forced to fall back upon traditions of the past, is far from being in a flourishing condition.

The plates are printed by Bemrose & Sons, Ltd., Derby and London

The text at the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh