|

|

MASTERPIECES

PUVIS DE CHAVANNES

(1824–1898)

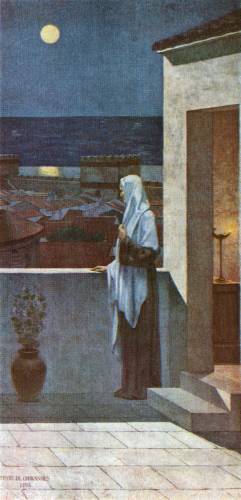

PLATE I.—SAINT GENEVIEVE KEEPING WATCH OVER SLEEPING PARIS. Frontispiece

(In the Panthéon, Paris) This composition, so great in its simplicity and so beautiful in execution, is the last work of the great artist. The model who posed for the saint watching over the city was Puvis de Chavannes' own wife. Both he and she died very shortly after its completion.  Puvis

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Page | |

| Introduction | 11 |

| The First Years | 16 |

| The Glorious Years | 31 |

| The Last Years | 53 |

| The Landscape Painter | 66 |

| Plate | ||

| I. | Saint Genevieve keeping Watch over sleeping Paris | Frontispiece |

| In the Panthéon, Paris | ||

| Page | ||

| II. | The Piety of Saint Genevieve | 14 |

| In the Panthéon, Paris | ||

| III. | The Poor Fisherman | 24 |

| In the Musée de Luxembourg, Paris | ||

| IV. | Ludus pro Patria | 34 |

| In the Museum, Amiens | ||

| V. | Repose | 40 |

| In the Museum, Amiens | ||

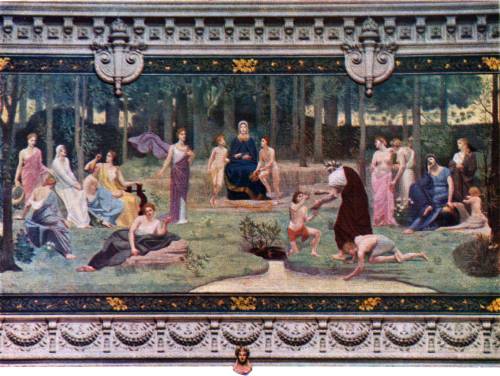

| VI. | The Sacred Wood dear to the Arts and the Muses | 50 |

| In the Museum, Amiens | ||

| VII. | Letters, Sciences, and Arts | 60 |

| In the Amphitheatre of the Sorbonne | ||

| VIII. | War | 70 |

| In the Museum, Amiens |

GLORY does not dispense her favours to the deserving with an equal bounty. Painters as well as authors often suffer from the caprices of the inconstant goddess. While there are some who, guided by her benevolent hand, attain the[12] pinnacle of fortune at the first attempt and almost without effort, other artists with a genius akin to that of Millet live in a state bordering upon penury and die in destitution. Renown seeks them out later, much too late, and tardy laurels flower only upon their tomb.

Puvis de Chavannes for a long time fared scarcely better than these illustrious mendicants of art. He experienced the bitter pangs of injustice, the hostility of ignorance, the discouragement of finding himself misunderstood. If he was spared the extreme distress of Millet, it was solely because he was the more fortunate of the two in possessing a small private income. But nothing can crush the spirit of the born artist; neither contempt nor ridicule can hold him back. Puvis de Chavannes was endowed with a valiant and a tenacious spirit. Entrenched within the loftiness of his artistic ideal, as within a tower of bronze, he was steadfastly scornful of critics, affecting not to hear them; and never would he consent to disarm them by concessions that in his eyes would have seemed dishonourable. Yet this rare probity brought its own[14] reward. The great painter attained the joy of seeing himself at last understood, and not only understood but admired during his life-time. He must even have derived an ironic satisfaction from counting among his warmest adherents certain ones who had formerly been conspicuous as his most violent detractors.

(In the Panthéon, Paris)

In this composition, exceptionally fine in feeling, Puvis de Chavannes shows how much importance he attached to landscape, which was the natural setting of his paintings, and which he treated with as much care as his personages themselves.

Today the glory of Puvis de Chavannes shines forth in uncontested splendour. No one dreams of comparing him with any of his contemporaries, because his art reveals no kinship with that of any one of them. He is recognized as the successor and the equal of the great fresco painters of the Italian Renaissance. Even to these he owes nothing, having borrowed nothing from them. But he shares with them his passionate love of truth, his nobility of inspiration and sincerity of execution. There are no longer insinuating and derisory shakings of the head in the presence of his works. One must be devoid of soul in order not to sense their beauty. Even the ignorant, in the presence of this form of art which they do not understand, gaze upon it with respectful wonder, as upon something very great, the content of which they fail to make[16] out, although they realize its power from the inner emotion they experience.

"My dear boy," wrote Puvis de Chavannes to one of his pupils, "direct your soul compass-like, towards some work of beauty; that is the way to achieve it in its entirety."

It is because he directed his own soul, compass-like, only towards works of a noble and pure beauty, surrendering himself with all the ardour of his impetuous and vibrant nature, that Puvis de Chavannes has taken his place as one of the noblest figures, not only in contemporary painting, but also in the painting of all times.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes was born at Lyons, December 14, 1824. His parents were in affluent circumstances and were connected with one of the old Burgundian families. His father pursued the vocation of chief engineer of mines, at Lyons. In the registry of births, in which the new-born child was entered, the father is designated simply by the name of Marie-Julien-César Puvis. The honourable title of "de Chavannes," claimed later and with[17] good right by the family, was confirmed to him by a decree of the Court of Lyons, bearing date of May 20, 1859.

Young Puvis de Chavannes was sent, first to the Lycée at Lyons, later to the Lycée Henri IV, at Paris. But nothing either in the boy's tastes or in his aptitudes gave any hint of his future vocation; he showed no special inclination for drawing, nor even for art in general. Son of a mining engineer, he applied himself naturally to the exact sciences; and he would probably have donned the uniform of a polytechnic student, had it not been for an illness which the family looked upon as most unfortunate, but which posterity regards as providential. The young man was forced to interrupt his studies and bid good-bye to mathematics. Two years later he took a trip to Italy, in the company of a young married couple. In true tourist fashion he made the rounds of museums and churches; he conscientiously inspected the great masterpieces in which the peninsula abounds; but, by his own admission, he brought back no real profit from his travels. They were not, however, entirely futile, since they awakened in him the desire to become[18] a painter. Upon returning to France he announced his determination to his family, and having won their consent, entered the studio of Henri Scheffer, brother of Ary Scheffer.

Italy, seen too hastily, had taught Puvis de Chavannes nothing: the studio hardly served him to better purpose. But, through contact with Henri Scheffer, he acquired a respect not only for art but for the conception which each one must form of it for himself. The young neophyte, who was destined in later years to be himself a living example of fidelity to an ideal, remained forever thankful to the author of Charlotte Corday for having imbued him with this noble sentiment. He always retained of him, throughout life, an affectionate and grateful memory.

Scheffer's paintings, however, were far from satisfying his personal conception of art. Before very long he left his studio and betook himself to that of Delacroix. The latter admitted him readily; but the new pupil was not slow in discovering that here again he was out of his element. The great romantic painter, although an admirable artist, was a mediocre instructor. He alone, for that[19] matter, could risk the violent colour schemes with which he covered his canvases; his pupils succeeded only in accentuating a debauch of thick-spread pigments by coupling together tones that cried aloud from the walls of the studio. The instinct of harmony and of proportion which was already awakening in Puvis de Chavannes, revolted against these audacities: he found himself ill at ease in the midst of this orgy of colour. It was after no such fashion that nature appeared to his eyes. He had about made up his mind to leave the studio of Delacroix when the latter, angered by criticisms and piqued at seeing the attendance falling off, decided to close his doors.

It was at this time that young Puvis entered the studio of Couture. There again his stay was brief, and we find in his work few traces of the lessons there received. Once again it was only the conventional and artificial that were held up as object lessons for that young soul enamoured of the truth, for those wide-opened eyes that saw nature precisely as she is, and not under the tinsel glitter of fantasy under which the studio of the period draped her. It followed that he learned nothing[20] from that school; nevertheless, he did not disown it. In the annual Salon Catalogue, Puvis de Chavannes continued to proclaim himself a pupil of Scheffer and of Couture.

Once again the young painter found himself without a master, yet still eager to learn and as yet equipped with only a mediocre and highly defective rudimentary training. Convinced that he would never obtain the right start in any of the studios of the French capital, he determined, in company of one of his friends, Beauderon de Vermeron, to go in search of definite guidance, back to that same Italy which he had visited the first time with such small profit. This time he studied all the periods, all the schools, all the methods of Italian painting; he visited both Rome and Florence; and yet all his sympathies, as he himself declared, went out instinctively to the Venetian school which had produced Titian, Tintoretto, and, greatest of all, Veronese, inimitable prince of fresco and of decoration.

Returning to Paris, Puvis de Chavannes no longer dreamed of soliciting the guidance of any school; henceforth he was to pursue his own path,[21] to give heed only to his own temperament, to draw his inspiration only from nature herself. In the Place Pigalle he hired a studio, the same which he was destined to occupy for forty-four years, and which he quitted only two years before his death. Later on he possessed another, at Neuilly, in which to work upon his larger compositions, since there would not have been space enough for them in the Montmartre studio. Whatever the weather, through cold and through heat, Puvis de Chavannes could be seen, for more than thirty years, making his way on foot, with long, rapid strides, from the Place Pigalle to Neuilly or in the reverse direction. This daily promenade grew to be a necessity; it was the sole recreation of this painter so enslaved by his art that in a certain sense he might be called a Benedictine of painting.

In 1852, the date when his real career began, Puvis de Chavannes was twenty-eight years of age. He was at this time a handsome young fellow, tall of stature and large of frame, quick-witted, jovial and enthusiastic, and combining the whole-souled simplicity of the artist with the polished manners of a man of the world, inherited from his[22] father. Many people conceive of Puvis de Chavannes as melancholy and sombre. Nothing could be further from the truth. He was fond of all the joys of living, friendly gatherings, abundant good cheer. But what he prized above all, thanks to the perfect balance of his physique, was the ability to apply his robust health to incessant work, which he pursued without intermission up to the day of his death.

In 1850, Puvis de Chavannes made his début by sending to the Salon a Pietà, which was accepted. His joy was great, for it was the joy of the first step. Later on, his satisfaction in that picture diminished. It had certain defects, and gave evidence of inexperience, which the young painter was quick to perceive. That same year he painted Jean Cavalier at the bed-side of his Mother, and an Ecce Homo, bold in execution and violent in tone.

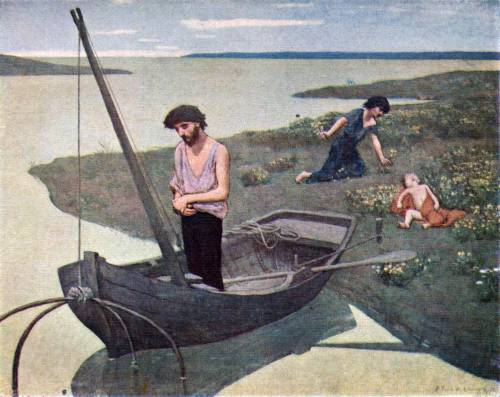

(In the Musée de Luxembourg, Paris)

No one else, excepting Millet, had the skill to render with so much truth the physical and moral distress of the unfortunate. This resigned fisherman, bending his back under the inclement sky, is a veritable masterpiece, both in execution and in observation.

In 1852, the pictures which he submitted to the Salon were rejected by the jury, and this ostracism continued for several years. It was an epoch when every effort towards artistic independence was officially and systematically repressed. The[24] young artist was not alone in disfavour; he shared it with a number of his friends, some of whom were already famous, or at least well known. Equally with himself, Courbet, Dupré, Barye, Rousseau, Millet, Troyon, Corot, Diaz and Delacroix found themselves ejected from the doors of the temple. In the eyes of the Academy, they were all of them madmen or revolutionaries; for his part, he was treated with less honour: he was regarded as a maniac of no importance. His exclusion lasted for nine years, during which the critics and the public united in making him the target for their sarcasms.

Puvis de Chavannes was always keenly sensitive to criticism; it cut him to the quick, but he prided himself on showing no outward sign. He repaid it by affecting the most complete disdain. When anyone in his presence bestowed only a qualified praise on one of his works, his lips would betray his scorn in a faint crease, which Rodin, another misunderstood giant, has admirably caught in his buste of the painter. As it happened, however, Puvis de Chavannes was rarely fortunate in having the encouragement and[26] support of such an admirable companion as the Princess Cantacuzène. That splendid woman, of exceptional intelligence and distinction, enjoyed art and understood it; she fell in love with Puvis de Chavannes and became his wife. "Whatever I am and whatever I have done," wrote the painter, "is all due to her." Throughout more than forty years, she filled the rôle of beneficent genius to the artist, the Egeria whose voice he never failed to heed. Puvis de Chavannes had worshipped faithfully at her shrine; and when she died, he felt that the term of his own life had reached its end. He survived her scarcely more than a few months.

Under the shelter of her far-sighted affection, the artist closed his ears to hostile comments, and followed his bent, without trying to modify his manner of seeing and feeling nature. None the less, the paintings of this period are far from perfect; a certain constraint is apparent in them, due to inexperience and also to some lingering influence either of his studio training or of Italy. The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, The Village Firemen, Meditation, Herodiade, Julie,[27] Saint Camilla at the bedside of a dying man, while they reveal some very genuine personal qualities, are none the less somewhat reminiscent of the manner of Couture, by whom he seems to have been most directly influenced.

His first real picture, the one which first marked and fixed for all time the artist's personality, was Peace, now in the Museum at Amiens. So much knowledge and so much harmony were displayed in this picture that the jury simply did not dare reject it. What is more, it won for its author a medal of the second class. He was not slow in giving it a companion piece, in the shape of a painting entitled War, which is now also at Amiens.

In the first of these pictures, the one consecrated to the pleasures of Peace, everything seems quite academic, the poses, the composition, the countenances: and yet, there is no stiffness, everything is vibrant, alive, palpitating in a serene and luminous atmosphere. The artist has herein magnificently demonstrated the truth of a phrase which he wrote to Ary Renan, in the course of a trip which the latter took to Italy: "Just as you[28] yourself feel and have very well expressed, no study of other artists' work can trammel one's originality." Neither the memory of Italy nor the influence of Couture had prevented him from asserting himself, and that, too, vigorously.

War is, if anything, superior to Peace. The painter is here wholly himself. There is no longer in his work any trace of outside influence. And what vigour there is, what eloquence, in the simplicity of the composition! Is there in existence a more admirable argument against war and its horrors? Beside the corpse of a young warrior, a father and mother are prostrated, voicing aloud their anguish; and meanwhile the conquerors, approaching from the far horizon black with devastation and slaughter, blow their victorious trumpets and urge their horses forward towards the group of mourners.

From that moment, Puvis de Chavannes began to command attention. He was discussed more acrimoniously, more passionately than ever; no one could neglect him nor pretend not to have heard of him.

[29] The government bought Peace, but refused to purchase War, in spite of the fact that the two paintings were companion pieces. In order to prevent them from being separated, the artist generously donated the second picture.

In 1863 came a new series representing Labour and Rest. Faithful to his principles, the author gathers together on his canvas the entire cycle of actions and ideas suggested by his subject.

In Labour he has placed in the foreground a group of blacksmiths, representing, in his eyes, the fully developed type of the worker, because of the degree of their exertion, the vigour of their action. While two of them stir the fire, the others, armed with heavy sledges, strike alternate blows upon the anvil. At no great distance, some carpenters are squaring the trunks of trees; beyond, on the plain, a peasant can be seen, guiding his ploughshare through its furrow. In the foreground there is also a woman, nursing a young child. The entire cycle of human toil is glorified in this single painting.

Repose shows us an old man seated, giving to the young folk grouped around him wise counsel,[30] drawn from his long experience. Nothing could be more graceful than the relaxed postures of the different figures, who, we feel, are listening with real attention.

Since these four pictures, Peace, War, Labour, Repose, were the interpretation of general ideas, the artist could not give them any precise setting, any local colour. The nude, which is employed for all the figures, was his sole means of obtaining absolute truth.

Already at this period one perceives in Puvis an anxious endeavour to sacrifice all the little easy methods of winning acclaim, in order to be free to concern himself solely with the harmony of his subject as a whole. Throughout his entire life, he was destined to have no greater preoccupation than that of effacing himself completely, and forcing the public, when in the presence of his work, to see nothing but the work itself and to give not a thought to the painter.

During the year 1864, the results of Puvis de Chavannes' industry were fairly abundant. At the Salon, he exhibited two very beautiful canvases, Autumn and Sleep.

[31] The first of these two pictures is symbolic and represents the different ages of life in the form of women of unequal years. One of them, her pensive face already marked with lines, watches her companions gathering flowers and fruit, symbols of youth.

This work, charming in composition, is now in the collection of the Museum at Lyons.

Sleep, a large decorative composition, after the manner of Peace and War, is in the Museum at Lille.

All these works, acrimoniously discussed and unjustly attacked by the critics, made the name of Puvis de Chavannes widely known without augmenting his reputation. The general public, habituated to the stereotyped, elaborate, ornate school, understood nothing of such deceptive simplicity. His canvases would not sell. Even the government had made no more purchases since its acquisition of Peace. It had even refused to acquire War, when the artist offered it. As we have already said, sooner than have the two pictures separated, Puvis made up his mind to donate it.

[32] Commissions failed to come in, and nothing afforded hope that this condition of affairs was likely to change, when chance threw in the path of Puvis de Chavannes a man whose providential intervention completely transformed his destiny.

At about this epoch the city of Amiens had started to build a museum. The architect of this enterprise, M. Diot, came to see Puvis de Chavannes and said to him:

"I saw your paintings in the Salon of 1861, and was greatly pleased with them. In the edifice which I am at present constructing, there are some vast surfaces to be covered. Are your two pictures, Peace and War, still in your possession? I could find immediate use for them."

Puvis de Chavannes replied that the two paintings in question belonged to the State. The city of Amiens immediately solicited the concession of them, which was courteously granted.

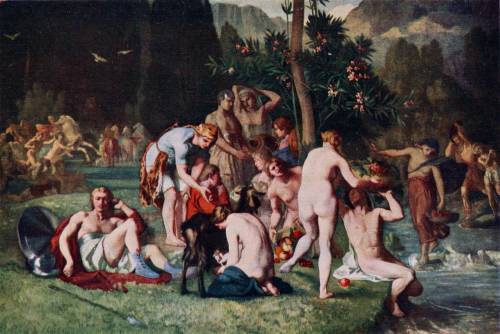

(In the Museum, Amiens)

This great composition, of which the present plate gives only a fragment, is numbered among the most beautiful productions of Puvis de Chavannes, because of the harmony of its parts, the nobility of the postures and the charm of its detail.

The paintings were placed in the grand gallery on the first floor, where they produced a most beautiful decorative effect. Puvis de Chavannes, delighted at this unhoped-for good fortune, offered to complete the decoration of the gallery, by painting[34] the panels occupying the spaces between the windows. The illumination is exceedingly bad, but with infinite art the painter succeeded in harmonizing his compositions with the atmosphere and light of the room. It should be noted further that the subjects treated in the panels on the right gallery relate to the picture of War, which faces them; they are a Standard-Bearer and a Woman weeping over the ruins of her home. The same holds true of the painting consecrated to Peace, the corresponding panels being a Harvester and a Woman spinning.

Puvis de Chavannes considered himself fortunate in having two of his works which he so greatly loved find a place in a museum. The municipality of Amiens was none the less delighted in possessing them; it gave proof of this by once more sending its municipal architect to him on a special embassy:

"I need two more mural paintings to decorate the main staircase of the museum. Do you happen to have what I need ready made, as you did the other time?"

The architect was jesting. Puvis de Chavannes[36] betook himself to a corner of his studio, and unrolling two canvases, presented them to M. Diot:

"Here are what you want. These two pictures are of the same dimensions as Peace and War; they represent Repose and Labour and form part of the same series. Will they serve your purpose?"

They served the architect's purpose to perfection. Unfortunately the city of Amiens did not have the money to pay for them. The difficulty was explained to the artist who, with his customary disinterestedness, made a present of both the paintings. They were soon stretched in the places for which they were intended, in a framework of fruits and flowers, and produced an admirable effect. The municipality of Amiens was so well satisfied with these paintings that it decided at the cost of great sacrifices to commission Puvis de Chavannes to prepare a large composition destined to occupy the entire upper panel of the staircase on the side of the grand gallery. This panel was intersected by two doorways.

Puvis de Chavannes set to work immediately. In the Salon of 1865 he exhibited his Ave Picardia Nutrix, destined for the Museum of Amiens.

[37] The painting produced a veritable sensation. Even the unskilled in art experienced an instinctive emotion in the presence of this important canvas which they did not fully understand, but which they felt to be sincere; as to the artists, they were obliged to acknowledge that the painter whom they had scoffed and derided, and who had now produced the Picardia Nutrix, was unquestionably a master.

The Ave Picardia Nutrix is a glorification of the fertility and richness of the land of Picardy. The artist has wished to represent in a succession of episodes, harmoniously related one to another, all the products of the soil and all the local industries from which Picardy draws its prosperity.

To this end he has grouped his figures in the setting of a Picardian landscape, quite faithful in colour and in line. M. Marius Vachon analyzes the painting as follows:

"Beneath the orchard of a vast estate some peasants are turning a flour mill; women are bringing apples for a keg of cider; masons are building the walls of a house, and an old woman is spinning on her distaff the native hemp. Along[38] the banks of a stream, women are weaving fish nets; carpenters are constructing a bridge; boatmen are steering heavy-laden barges. Add to these professional labours the incidents of work-a-day life, which are taking place on every side, charming incidents, picturesque and touching; a little lad, carrying a heavy basket of fruit on his head, eager to show his strength before his elders; a mother, nursing her youngest born; some women bathing under the shadow of the willows. The composition is abundantly suggestive of delicate impressions; and it forms a magnificent decoration for the edifice in which it has been placed."

When the painting had been installed in its position in the vestibule of honour on the main floor, the municipality of Amiens perceived that the fourth side of the staircase, the only one not decorated, was precisely the one that best lent itself to the development of a painting, because of its considerable surface. The ceiling, it is true, darkened this vestibule, owing to its insufficient window space. It was, furthermore, adorned by a painting by Barrias. Nevertheless the city[40]

determined to replace the ceiling by a skylight, on condition that Puvis de Chavannes would paint the vacant panel thus made available.

(In the Museum, Amiens)

This work is one of the earliest by this great artist. It is very interesting, because it still shows the influence of Couture's studio, where Puvis de Chavannes had been a pupil. It serves as a point of comparison for determining the evolution of the artist's talent.

However, the resources of the municipality did not permit it to incur so great an expense. It appealed to the State, which curtly refused its coöperation. The city fathers of Amiens were in despair, the painter not less so. What was to be done? Wait until the municipality, through slow economies, was in a position to order the picture? Puvis de Chavannes, who had grown enthusiastic over the task, was boiling with impatience and listened day by day, as he expressed it, to hear if no breeze was blowing his way from Amiens.

But when the breeze remained persistently unfavourable, Puvis de Chavannes, growing tired of waiting, decided to execute the panel in any case, come what might. And he composed the admirable fresco which bears the name of Ludus pro Patria.

Everyone knows the subject of this painting, which has passed into a legend. In a plain traversed by a running stream, some young men[42] are engaged in a game of rivalry with spears. On a knoll, an old man, surrounded by women, serves as umpire. He follows, with attentive eye, the fluctuations of the game, while a young lad, in a pose charming for its relaxation, rests one arm around his neck. Behind him a young woman holds out her baby for its father to kiss. On the left of the picture, seated at the foot of a tree, or grouped around a fountain, young girls await the end of the game in which their brothers or their betrothed take part. One of them leans towards an aged minstrel and begs him to play some dance music after the game is over.

All these groups are harmoniously disposed in an open-air setting, dotted over with cottages and stately trees, enveloped in a soft and mellow light.

This picture reveals the artist's predilection for children, a very curious and touching predilection to discover in a painter whose own fireside was never gladdened by childish laughter. Let us examine the Ludus pro Patria; in this picture Puvis de Chavannes has been lavish of childhood games and pastimes. Notwithstanding that his art was before all else synthetic, and gained its effects[43] from harmony of attitude rather than from finish of figures, he plainly expended loving care in modelling those delicate and charming little bodies, which he has endowed with infinite grace. Is there anything more adorably exquisite than the gesture of the infant stretching out its plump arms towards its father? And does not the child standing before the group by the fountain reveal the master's tender solicitude for these little beings whose absence from his domestic life he probably regretted?

The distinguished custodian of the Museum at Amiens showed me the corner of the balustrade on which the painter rested his elbows, in front of the group of which that child forms part. After some moments of contemplation, he might be seen to mount his scaffolding, brush in hand, to add a few strokes, some new tint to that delightfully modelled little form.

The Ludus pro Patria is something more and something better than a beautiful picture; it is a symbolic work in which the noblest conceptions of patriotism are exalted. With his incomparable synthetic art, Puvis de Chavannes has endeavoured to show all the diverse manners of serving usefully[44] one's native land. Young women, bearing the tender burden of nursing children, are rearing for their country a valiant generation, which before long will be augmented through the robust girls grouped on the left, awaiting the advent of husbands. The children, grown to manhood, will practise games of strength and skill which will render them capable of defending their common patrimony. The old man himself has his rôle assigned in this ideal commonwealth; ripened by experience of life, he supplements the feebleness of his arms by the wisdom of his lessons; he is the honoured counsellor, the arbiter of full justice, who restrains the ardor of youth within the path of reason.

The cartoon for this magnificent panel was exhibited in the Salon of 1881; it achieved a unanimous success. The State acquired it, and at the same time commissioned Puvis to paint the picture itself for the Museum of Picardy. The finished work, in its proper dimensions, found a place in the Salon the following year, and gained its author the medal of honour from the Society of French Artists.

[45] We have followed Puvis de Chavannes in his decoration of the Museum of Amiens, from the beginning to the end of his artistic career, without regard to chronological order, because of the interest which he himself took in this extensive work, which was, one might say, his constant preoccupation. Accordingly we must go back in point of time and follow step by step this astonishing and genial worker whose accomplishment is disconcerting in its power and its fecundity.

The first works executed for the Museum of Amiens had attracted public attention to him. The municipality of Marseilles had just crowned the important enterprise of bringing the waters of the Durance into the city, by erecting a sumptuous Public Waterworks, bearing the name of the Palace of Longchamps.

Two great mural surfaces enclose the principal staircase. It was decided to decorate them with paintings. And when the time came to choose the artist, a unanimous agreement was reached on the name of Puvis de Chavannes.

The latter, being notified, accepted joyfully, as he accepted all occasions of converting a noble[46] vision of art into a reality. And what finer fortune could come to an artist that to celebrate Marseilles, the sun-bathed city, vibrant with light, crouching royally on the azure mantle of the Mediterranean?

Puvis de Chavannes hastened to the ancient Ligurian city. He calculated the difficulties of composing a great decorative composition, free from banality, out of the habitual elements of a seaport,—a subject a thousand times treated and perilous of execution. He sought, he studied, he promenaded the quays, he strode the length and breadth of the city. At last the enlightening flash he awaited came in the course of a trip to the Chateau d'If. In the presence of that noble panorama of the city seen from the sea, he remained as if dazed, realizing that he had found what he was in search of. He would not paint Marseilles with the sea as a decorative background; it was the city herself that should form the background, and not the sea. He had his two pictures in his grasp.

And without stirring from the spot, while his friends took luncheon, he remained seated on the rocks, making notes and sketches, in order to fix[47] fully in his mind "the line and colour of that marvellous maritime landscape."

The first of these pictures, Marseilles the Greek Colony, stands for the entire history of the Phocian city from its foundation to the present time. But, following his essentially synthetic method, he painted, not the successive transformations of Marseilles, but symbolic figures of the sources to which she owes her grandeur and her prosperity.

In the background is the strand, which as yet is only a natural harbour. Along the shore, vessels are seen building; these are the symbol of activity. Further off, horses are bringing merchandise towards the boats about to sail, symbol of the commercial instinct; masons, carpenters, stonecutters, are zealously plying their craft; and palaces, storehouses, and churches arise, symbols of wealth and of taste in art.

Among the accessory features are a woman vendor spreading before other women rich fabrics and pearls, and some slaves conveying towards the city jars of oil and skins filled with wine.

In Marseilles, Gateway of the East, a ship is[48] seen, laden with travellers, making its way into port. All these passengers are Orientals, recognizable by the gaudiness of their garments: they admire the panorama of the rich city whose fortifications, churches, and palaces stand out in bold relief against the ruddy light of evening.

An atmosphere of warmth and brilliance emanates from these two paintings, of which the city of Marseilles has shown herself justly proud.

When Puvis de Chavannes received a commission for a mural painting he gave himself ardently to his task, but at the same time intermittently. Contrary to a generally accepted belief, his genius was not the result of "long patience," but rather the realization of a vision. He never applied himself to a painting if some external cause, no matter what, had deadened in him the essential inspiration. In such a case, he would revert to some other work which his mind could "see better" on that particular day. In this way we can understand how he could carry forward simultaneously several works of equal importance, and at the same time paint in addition occasional easel pictures.

(In the Museum, Amiens)

This painting, admirable in execution, is quite interesting to study, because it serves to show in what a purely personal manner, wholly detached from mythological traditions, Puvis de Chavannes interpreted Antiquity.

[51] Following the example of Marseilles and Amiens, the city of Poitiers, which in 1872 had just completed the building of a City Hall, commissioned Puvis de Chavannes to decorate the main staircase.

The two subjects chosen by the artist, with the approbation of the municipality, were as follows:

First panel:—"Radegonde, having retired to the Convent of the Holy Cross, offers an asylum to the poets and protects Literature against the barbarism of those days."

Second panel:—"The year 732: Charles Martel saves Christendom by his victory over the Saracens near Poitiers."

The legend of Radegonde is well known: "The virtuous spouse of Clotaire, fleeing from the brutality of that crowned free-booter and hiding in a convent in order to escape his pursuit." But this convent is by no means a cloister; the practice of arts and letters is pursued alternately with the singing of psalms.

The door stands open to poets. One of them,[52] Fortunatus, passing through Poitiers, stops there and is received with cordial hospitality, and conceiving for the saintly queen a delicate and chaste love, he remains for twenty years in this abode in which he purposed to spend only a few days.

Puvis de Chavannes has magnificently rendered the poetic beauty of this historic episode by representing one of the fêtes given by Radegonde in the Convent of the Holy Cross.

In the second panel, we see Charles Martel returning to Poitiers, victorious over the Saracens and receiving the benediction of the bishops. Here the artist's brush attains a vigour of expression such as in all his life he found but few occasions to employ. The countenances of the bishops, notably, stand out with a relief and an energy that are remarkable.

M. Marius Vachon relates that he once asked the artist, who was a personal friend, to what documents he had recourse in order to give such forbidding features to the prelates in his painting:

[53] "I got the suggestion for them," he replied, laughing, "from an old set of chess men, consisting of the coarse and grouchy faces of knights and jesters."

In the days following the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune, the Government conceived the project of decorating the Panthéon, which had just been once more secularized, in order to convert it into a temple wherein all the shining lights of the nation could be brought together and honoured.

M. de Chennevières, who at that time was director of the Beaux Arts gave the first place, in that illustrious line, to the noble and serene Genevieve, patron saint of Paris, incarnate ideal of patriotism.

Accordingly it was a series of religious paintings that M. de Chennevières required of Puvis de Chavannes, when he entrusted him with a large share of the decoration.

This type of painting, although new to Puvis[54] de Chavannes, failed to intimidate him. He had too much patriotic fire, more than enough Christian faith, and above all too thorough a mastery of his profession not to approach this task with full confidence. It is enough to visit the Panthéon just once in order to be convinced of this. A more magnificent realization of Saint Genevieve could not be conceived of, even in dreams. But are these paintings to be classed with religious art? One would hesitate to assert it, if the pictures habitually consecrated to religious themes are to be taken as a standard. But they are something better than that, because the virgin protectress of Paris is in these pictures profoundly human; she is brought very close to us, and we see her despoiled of the aureole that would have removed her too far from our vision and our hearts.

The whole world knows, at least through reproductions, the series of paintings consecrated to the life of this saint. First of all, we have Saint Genevieve as a child, singled out from a crowd by Saint Germain, because she is[55] marked with the divine seal. "I chose the hour," wrote Puvis de Chavannes, "at which history claimed possession of this heroic woman. These two are not an old man and a child, they are two great souls face to face. The glance which they ardently exchange is, in its moral significance, the culminating point of the composition."

Next in order comes the Piety of Saint Genevieve. The pious child is at her prayers before a cross formed by two interlacing branches. This is the prologue of a life filled with miracles, divine recompense accorded only to supernatural virtue. The artist has admirably reproduced the mystic fervour of that child whose future was foreordained to be so beautiful.

Subsequently, in 1896, the Government entrusted Puvis de Chavannes with the execution of two new panels, likewise dedicated to the life of Saint Genevieve. The two themes chosen were the following:

"Ardent in her faith and in her charity, Genevieve, whom the greatest perils could not swerve from her duty, brings sustenance[56] to Paris, besieged and threatened with famine."

"Genevieve, sustained by her pious solicitude, keeps watch over sleeping Paris."

These noble paintings were the last productions of the great artist. A sort of premonition told him that the end was near, in spite of his robust health. "How I shall devote myself to the Panthéon," he wrote, "when I am finished with the Hôtel de Ville! I intend it to be a sort of last will and testament."

In these last paintings, Saint Genevieve is no longer a child. Having attained womanhood, her saintliness is such that, from all sides, people come to take shelter behind her veil, like children around their mother, as soon as danger is announced.

For the purpose of portraying this hieratic and inspired figure, Puvis de Chavannes found the ideal model close at hand, in the noble woman who had associated her entire life with his. Genevieve bringing sustenance to Paris is the artist's wife who, already mortally ill, inflicted upon herself the most cruel suffering, in order to[57] pose in her husband's studio. The disease which was killing her was known only to herself, and she had the heroism to conceal it up to the supreme hour when, conquered at last, she was stricken down. In painting the pensive and dolorous attitude of Genevieve watching over sleeping Paris, the poor artist never once suspected that he was tracing for the last time the portrait of her who had been the consolation and the joy of his whole existence.

The unfortunate woman lacked the strength to play her rôle to the end; she was forced to take to her bed. The artist, no less heroic than she, feeling that his own life was slipping away with hers, yet wishing to complete this last work,—his testament—transported his easel beside the dying woman's bed, and there finished the sketches for his picture.

In the intervals of time between the paintings executed for the Panthéon, Puvis de Chavannes produced certain other large compositions in no wise inferior either in importance or in merit, notably, in 1883, a large painting for the Palace of Arts, at Lyons.

[58] The municipal government of that city, wishing to have the main staircase of the palace decorated, entrusted the execution to the great artist who was at the same time a compatriot. He felt a very special joy in accepting this commission, for he had always retained a vivid memory of the city of his birth.

He endowed it with three pictures of a very high order, one of which, The Sacred Wood, dear to the Arts and the Muses, is considered by many to be the artist's masterpiece.

Puvis de Chavannes breaks away from the mythological theme so often treated that it has become hackneyed. It is not on Helicon that he groups his Muses, but on the shore of a lake, in a setting of verdure softly illuminated by the rays of the moon. At the foot of a portico, Calliope is seen declaiming verses before her sisters. Some of the Muses appear attentive; others converse together; one of them is reclining lazily upon the grass. Euterpe and Thalia, heralded from the sky by song and the accompanying lyre, approach to join the group.

(In the Amphitheatre of the Sorbonne)

In this immense composition, in which the groups are balanced with admirable harmony, there is an exalted and pervading beauty. It makes itself felt in the prevailing mood of the subject as a whole, in the expressions of the several characters, in the naturalness of their attitudes and in the luminous clarity of the landscape.

[61] Antiquity, as treated by Puvis de Chavannes, loses nothing of its nobility, but quite the contrary. It even gains in real beauty, because his Muses profit by being despoiled of those conventional attitudes, in which an immutable tradition has trammelled them. The artist has retained only such of their attitudes as cannot detract in any way from the naturalness of their movements or their lines.

In the same Palace of Arts, Puvis de Chavannes painted two additional allegorical panels representing The Rhone and The Saône, both of which are admirably effective.

To about the same period belongs his well known painting, The Poor Fisherman, at present in the Musée du Luxembourg.

In this work, which he painted as a relaxation from his more extensive efforts, Puvis de Chavannes has tried to portray, as Millet so often did, all the sordid and lamentable misery of the slaves of toil, who bend their poor aching backs beneath the burden of physical distress and mental degradation. This work is a fine and eloquent lesson in humanity.

[62] In 1889, the Hôtel de Ville, in Paris, proceeding with the still unfinished decoration of its numerous halls and chambers, entrusted Puvis de Chavannes with the task of decorating the main staircase and the first salon in the suite of reception rooms.

On one wall of this salon, he painted Winter, on the other Summer. These two compositions are of imposing dimensions and admirable in execution.

Winter shows us a snow-clad stretch of forest landscape. Woodsmen are hauling the trunks of trees which others of their number have just felled. Nothing could be more impressive than his rendering of the desolation of winter; and the truth, the exactitude of the physical effort these men are putting forth, with every muscle straining tensely on the rope.

Summer shows us a delightful and smiling landscape flooded with light; bathing women plunge their nude forms beneath the water, while a mother, seated on the grass, nurses her new born child. In this picture Puvis de Chavannes, who[63] was a landscape painter of the first order, has surpassed himself; the work is a miracle of open air and grateful shade.

Unfortunately, the room in which these two magnificent pictures are placed suffers from a deplorable want of light, and its scanty dimensions make it impossible to stand back at a sufficient distance to see them to advantage. The Hôtel de Ville should for its own credit assign them a place more in keeping with their worth.

For the museum at Rouen, Puvis de Chavannes painted an allegory entitled Inter Artes et Naturam, charming in fantasy and poetic feeling. According to his habit, he has grouped together in synthetic form the various things which constitute the wealth or serve to mark the characteristics of the province of Normandy.

Labourers heaping up architectural fragments preserved from all the various epochs proclaim the variety and antiquity of its monuments; its special art is represented by a young girl painting a tulip on a porcelain plate and by a lad[64] carrying a tray of pottery; its principal agricultural richness is revealed by the action of a woman, bending down a branch of an apple-tree, in order that her child may reach the fruit. And at the bottom of the picture flows the Seine, rolling its flood past a long sequence of manufactories, and bearing in its course heavily laden boats.

This picture is one of Puvis de Chavannes' most ingenious conceptions; furthermore, it possesses great charm of detail.

In 1891, the trustees of the Boston Museum approached Puvis de Chavannes with a request to decorate the main staircase of that edifice.

The negotiations were troublesome. In spite of his delight at having a new work to produce, in spite of the legitimate pride he felt in this homage paid to French art, Puvis de Chavannes hesitated to accept the commission. For the first time he faced the necessity of painting a canvas without having studied beforehand the physiognomy, the environment, the illumination of the space he was to decorate, and his artist's conscience suffered. Besides, certain misunderstandings[65] had arisen between American trustees and the painter; several times relations were on the point of being broken off; and no definite agreement was reached until after the lapse of four years.

Puvis de Chavannes began this work in 1895; he did not finish it until 1898. The surface to be covered was to be divided into nine large panels, three facing the entrance, three to the right, three to the left. The choice of subjects was left to him.

For the central panel Puvis de Chavannes chose a theme already treated twice by him: The inspiring Muses acclaim Genius, Messenger of Light.

Against a background of sea and of blue sky, a Genius with the radiant features of a child advances, holding a torch in each hand. At sight of the Genius the muses run forward and range themselves on each side.

The ninth muse, still floating through the air, hastens to rejoin her companions.

This whole charming group of women is deliciously painted and one is at a loss which to[66] admire the more; the originality of the artistic conception, or the peculiarly rare delicacy of the painter's skill.

The eight subordinate panels represent Bucolic Poetry, Dramatic Poetry, Epic Poetry, History, Astronomy, Physics, Chemistry and Philosophy. All these paintings produce a decorative effect of the highest order, and many critics consider, not without reason, that this group of frescoes in the Boston Library constitutes the masterpiece of Puvis de Chavannes.

However that may be, the authorities of the great American city are very proud of this absolutely unique decorative ensemble, and whenever any distinguished stranger passes through Boston he is conducted to admire it. Is not this a beautiful homage to French art, of which Puvis de Chavannes was one of the most glorious exponents?

There is, in the work of Puvis de Chavannes, so much harmony and balance; the place occupied[67] by each figure is so perfectly planned to accord the unity of the whole, that one does not perceive at first, because of the wise ordering of the assembled parts, how many-sided the artist's genius was. And so it happens that the landscape painter in him does not appear excepting under analysis. Yet few artists have advanced the science of landscape so far; indeed, in all his compositions it holds a position, if not of first importance, at least one equal to that of his figures. In his eyes it was not a matter of convention, a decoration, an accessory, but an indispensable part of the picture, so indispensable indeed that, without the landscape the picture would not exist. In short, it is in his landscape that Puvis de Chavannes has always placed the local colour of his compositions, and not in his figures. The latter are generally clad in antique fashion, in order to remain representative of humanity in general, but the setting is local: his Ave, Picardia Nutrix, for instance, shows us the land of Picardy with its level plains and its melancholy horizons: similarly, the two[68] frescoes in the Palace of Longchamps reproduce faithfully the sun-flooded coast of Marseilles and the animation of its quays;—and yet the hurrying crowds upon them belong to no definite race nor to any determinable epoch.

It is always so in the paintings of Puvis de Chavannes: the landscape and the living figures harmonize, fit in, complete each other, and the consummate art of the landscape painter yields in no way to that of the painter of figures.

(In the Museum, Amiens)

This work dates from the same period as Repose and Peace. It marks the début of Puvis de Chavannes in his career as an artist. In spite of some reminiscences of his training, his individuality already asserts itself, and the originality of composition is unmistakable.

Puvis de Chavannes has been criticized on the ground that in such of his pictures as evoke antiquity, he sacrificed accepted tradition and acquired knowledge. From this to a direct charge of ignorance was an easy step; and it was quickly taken. That the artist attached a mediocre importance to accuracy in decoration or antique costume, there can be no question. Truth, in his eyes, consisted less in the detailed reconstruction of garments than in the faithful representation of that eternally living model, the human soul, over which whole centuries have passed, without[71] availing to modify it. All else is merely accessory and secondary, if not actually negligible. At the same time, no one was ever more truly impregnated with the spirit of antiquity, as he had imbibed it from his readings, from his travels and from his own meditations. Contrary to what has been thought, he was not proud; nor held himself aloof from all other schools of painting except his own. Nothing could be further from the truth. Puvis was acquainted with all the schools; and no one admired more sincerely than he the great masters of each and every country. He had traversed Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands, examining, studying, admiring. And here is precisely wherein his great glory consists; that having studied all methods, analyzed all processes, he still remained true to himself,—in other words, that he was a painter of inimitable originality.

Puvis de Chavannes kept abreast of all the ideas that stand for personality and progress. Far from being a recluse, solely concerned with his own painting, he followed the contemporary[72] literary movement, and none of the happenings that took place around him escaped his knowledge.

Nevertheless, his chief preoccupation was his art and his desire to express, with his brush, the greatest possible degree of human nature. This he achieved in his magnificent series of immortal works; but it was only at the cost of a vast amount of conscientious labour. Few masters have had so keen an intuition of beauty, or a higher and more spontaneous inspiration; and no one, perhaps, has been so distrustful of himself, of his inspiration, of his intuition. He did not surrender himself to them until he had submitted them to the test of searching argument and uncompromising common sense. It is due to this careful weighing in the balance, to this wise mingling of youthful enthusiasm and mature severity that the work of Puvis de Chavannes owes that harmonious beauty that insures it an eternal glory.

And so, when in 1898 he passed away, not a dissenting voice was raised amid the concert of[73] eulogies and of regrets which marked his end. For a long time previous, Puvis de Chavannes had ceased to have detractors; admiration had stifled envy. And, from the moment that he crossed beyond the threshold of life, Puvis de Chavannes entered fully into immortality.

Musée du Luxembourg; The Poor Fisherman.

Panthéon; Saint Genevieve marked with the divine seal.—The Piety of Saint Genevieve.—Saint Genevieve providing for besieged Paris.—Saint Genevieve watching over sleeping Paris.—Two decorative Friezes, including Faith, Hope, and Charity, and a series of Saints.

Hôtel de Ville; Summer, Winter.—Victor Hugo offering his lyre to the city of Paris.

Amphitheatre of the Sorbonne; Letters, Sciences and Arts.

Museum at Amiens; Peace.—War.—Labour.—Repose.—A Standard-Bearer.—A Harvester.—A Woman weeping over the ruins of her house.—A Woman Spinning.—Ave, Picardia Nutrix.—Ludus pro Patria.

Church at Campagnat; Ecce Homo.

Palace of Longchamps (Marseilles): Marseilles, a Greek Colony.—Marseilles, Gateway of the Orient.

Museum at Marseilles: The Return from the Hunt.

Hôtel de Ville, Poitiers: Saint Radegonde gives asylum to the Poets.—Charles Martel re-enters Poitiers after his conquest of the Saracens.

Palace of Fine Arts, Lyons: The Sacred Wood dear to the Arts and the Muses.

Museum at Rouen: Inter Artes et Naturam.

Public Library, Boston: The inspiring Muses acclaim Genius, Messenger of Light.

Museum at Chartres: Summer.

Private Collections: Herodiade.—Autumn.—Sleep.

==--==--==

==++==++==