|

|

Artist Index

Winding the Skein

Frederic Lord LeightonLate President of the Royal Academy of ArtsAn Illustrated Record ofHis Life and WorkBy Ernest Rhys

London: George Bell & Sons1900

First Published, super-royal, 4to, 1895. Second Edition, revised, colombier 8vo, 1898. Third Edition, revised, crown 8vo, 1900.

Publishers' Note to Third EditionThe reception given to previous editions of this work encourages the publishers to hope that a re-issue in a smaller form may be appreciated. The present volume is reprinted with a few alterations and corrections from the second edition published in 1898. A chapter on "Lord Leighton's House in 1900," by Mr. S. Pepys Cockerell, has been added. The publishers take the opportunity to repeat their acknowledgments of assistance most kindly given by numerous owners and admirers of the artist's work. By the gracious consent of H.M. the Queen, the Cimabue in the Buckingham Palace collection, is here reproduced. Especial thanks are also due to Lord Davey, Lord Hillingdon, Lord Rosebery, Mrs. Dyson-Perrins, the late Mr. Alfred Morrison, Sir Bernhard Samuelson, Lady Hallé, Mr. Alex. Henderson, Mr. Francis Reckitts, the late Sir Henry Tate, the Birmingham and Manchester Corporations, and the President and Council of the Royal Academy, who have kindly permitted the reproduction of pictures in their possession. To the late Lord Leighton himself the author and publishers have to acknowledge their[Pg vi] indebtedness for a large number of studies and sketches, hitherto unpublished, as well as for his kind co-operation in the preparation of the volume. The author wishes also to record his thanks to Mr. M. H. Spielmann for permission to use his admirable account of the President's method of painting. By arrangement with the holders of several important copyrights, including Messrs. Thos. Agnew and Sons, P. and D. Colnaghi and Co., H. Graves and Co., Arthur Tooth and Sons, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, the proprietors of the Art Journal, the Berlin Photographic Company, and the Fine Art Society (whose courtesies in the matter are duly credited in the list of illustrations), the publishers have been enabled to represent many of the most popular paintings by the artist, and a selection of his famous designs for Dalziel's Bible Gallery.

Contents

[Pg viii]

List of IllustrationsI. FIGURE SUBJECTS.

With four exceptions all the reproductions are by the Swan Electric Engraving Company.

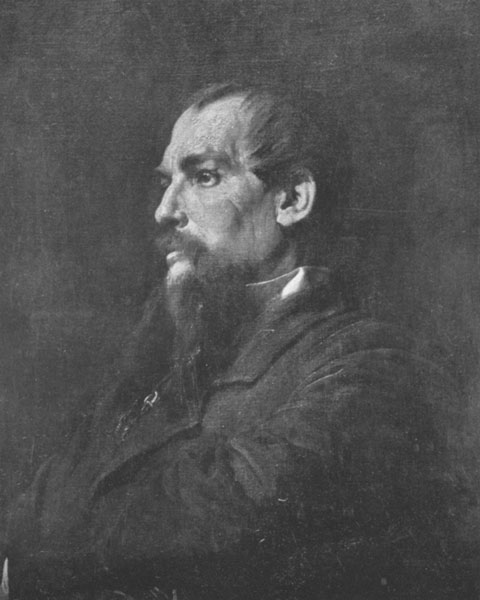

FREDERIC LORD LEIGHTON, P.R.A.LIST OF DIGNITIES AND HONOURS CONFERRED

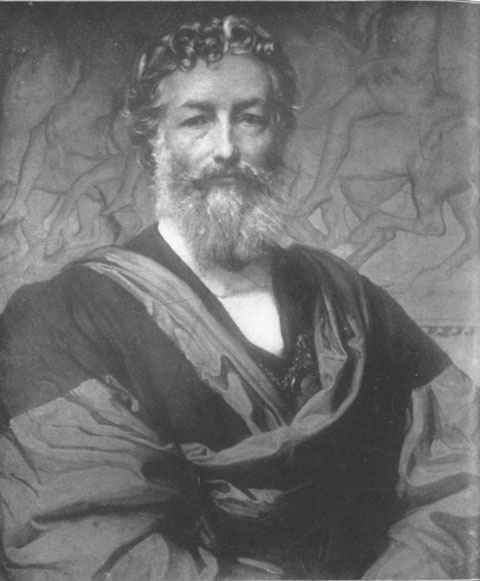

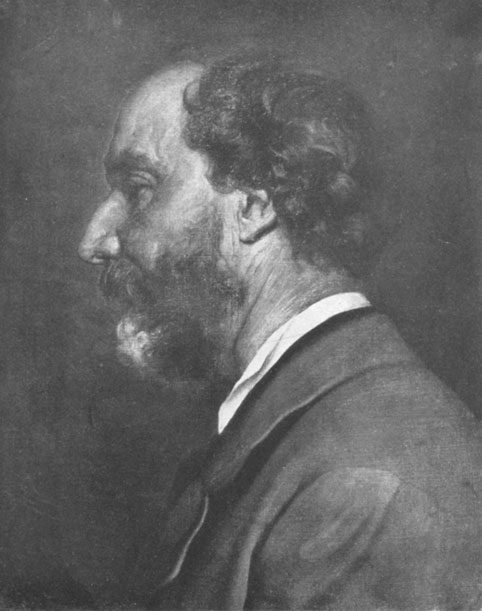

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST (1881)

FREDERIC LORD LEIGHTON, P.R.A.AN ILLUSTRATED CHRONICLECHAPTER IHis Early YearsTo Italy, at whose liberal well-head English Art has so often renewed itself, we turn naturally for an opening to this chronicle of a great English artist's career. Frederic Leighton was the painter of our time who strove hardest to keep alive an Italian ideal of beauty in London; therefore it is in Italy, the Italy of Raphael and Angelo and his favourite Giotteschi, that we must seek the true beginnings of his art. London made its first acquaintance with him and his painting in 1855, when the picture, Cimabue's Madonna carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence, startled the Royal Academy, and proved that a 'prentice work could be in its way something of a masterpiece. This picture, the work of an unknown young artist of twenty-five, painted chiefly in Rome, showed at once a new force and a new quality, and in its singular feeling for certain of the archaic Italian schools, showed, too, where for the moment the sympathies of the painter really lay. How far the potentiality disclosed in it was developed during the forty years following, how far the[Pg 4] ideals in art, which it seemed to declare, were pursued or departed from, the Royal Academy year by year is witness. Here, before we turn to consider the history of those later years, we shall find it interesting to use this first picture as an index to that period of probation, which is so often the most interesting part of an artist's history. In accounting for it, and finding out the determining experiences of the artist's pupilage, we shall account, also, for much that came after. Although Frankfort and Paris play their part, the formative influences of that early period, we shall find, carry us chiefly, and again and again, into Italy. Frederic Leighton was born on the 3rd of December, 1830, at Scarborough, the son of a medical practitioner. His father, Dr. Frederic Leighton, was also the son of a physician who was knighted for eminence in his profession. Thus we have two generations of medicine and culture in the family; but there is no sign of art, or love for art, before the third. This generation produced three children, all devoted to the graphic arts and to music, of whom the boy, Frederic was the eldest. A word or two more must be given to his forbears, on grounds of character and heredity, before we pass. Sir James Leighton, the grandfather, was Physician to the Court at St. Petersburg, where he served in succession Alexander the First, and Nicholas, with whom he was on terms of considerable intimacy. His son, Dr. Frederic Leighton, who promised to be a still more brilliant practioner, was educated at Stonyhurst, but after taking his M.D. degree at Edinburgh, just as he was rapidly acquiring the highest professional reputation, contracted a cold that led to a partial deafness. This made it impossible for him to go on practising with safety, and retiring to his study he turned from physical to metaphysical[Pg 5] pursuits. In spite of his deafness, as severe an embargo on social reputation as can well be laid, Dr. Leighton is said to have been equally noted among his friends for his keen intellectual quality and his urbanity. To be the son of his father, then, counted for something in our hero's career. Even in art, which Dr. Leighton did not care for particularly, the boy had very great opportunities. Before he was ten years old, he went abroad with his mother, who was in ill health; and already he had shown such decided signs of the furor pingendi during a chance visit to Mr. Lance's studio in Paris, that it is without surprise that we hear of him in 1840 as taking drawing lessons from Signor F. Meli, at Rome. During these early travels the boy's sketch books were full (we are told) of precociously clever things. The climacteric moment came early in his career. At Florence, in 1844, when he was fourteen, he delivered himself of a sort of boyish ultimatum to his father, who, after taking counsel of Hiram Powers, the American sculptor, wisely gave the boy his wish, and decided to let him be an artist. Powers when asked, "Shall I make him an artist?" exclaimed in no uncertain terms, "Sir, you have no choice in the matter, he is one already;" and on further question, the father being anxious about the boy's possibilities, said, "He may become as eminent as he pleases." Few art students of our time appear to have encountered more fortunate conditions, on the whole, than did Frederic Leighton in the years immediately following. The Florentine school of fifty years ago, however, was not the best for a beginner. It was full of mannerisms, which a boy of that age was sure to pick up, and exaggerate on his own account. At that time Bezzuoli and Servolini were the great lights and directors of the[Pg 6] Academy of the Fine Arts, and they delighted, naturally, in so able and so apt a pupil; that he found it hard to shake off their teaching becomes evident later. Those who had the good fortune at any time to have heard Lord Leighton describe his early wanderings in Europe, must have been struck by the warmth of his tribute to Johann Eduard Steinle, the Frankfort master, who did more than any other to correct his style, and to decide the whole future bent of his art. Steinle, whose name is barely known to us in England, was one of that remarkable school of painters, called familiarly "the Nazarenes," because of their religious range of subjects, who were inspired originally by Overbeck and Pfühler. Leighton in recent years described him as "an intensely fervent Catholic;" a man of most striking personality, and of most courtly manners, whose influence upon younger men was fairly magnetic. In the case of this particular pupil, certainly, his intervention was of most powerful effect. Religious in his methods, as well as in his sentiment of art, the florid insincerities and mannerisms of the Florentine Academy, as they were still to be seen in the young Leighton's work, found in him an admirable chastener, but it took many years of painfully hard work, lasting until 1852, to undo the evil wrought by decadent Florence. Prior to this fortunate intercourse with Steinle, the student had an old acquaintance with Frankfort, which, like Florence, seemed destined to play a great part in his history. Before going to Florence, and deciding on his artistic career, in 1844, he had been sent to school in Frankfort. He returned there from Florence to resume his general education, and on leaving at seventeen, went for a year to the Städtelsches Institut.

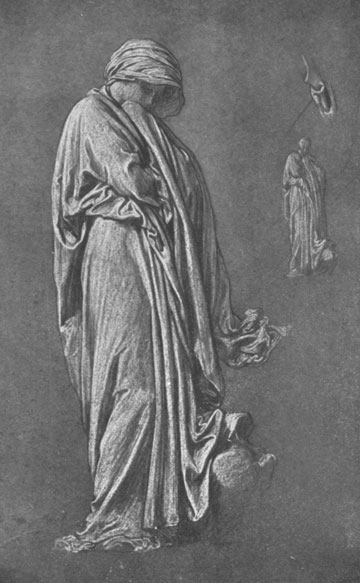

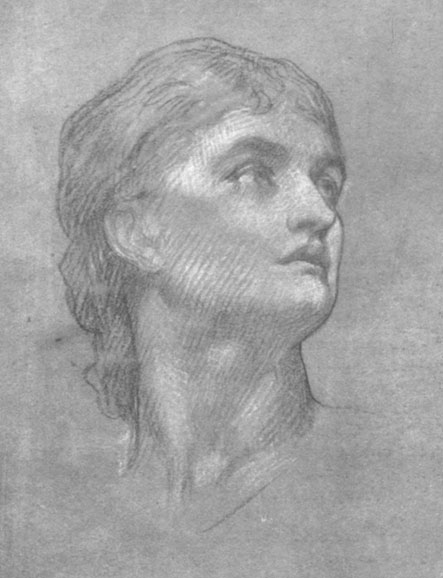

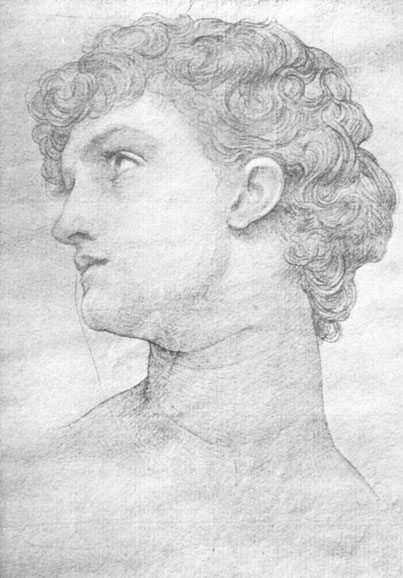

TWO EARLY PENCIL STUDIES

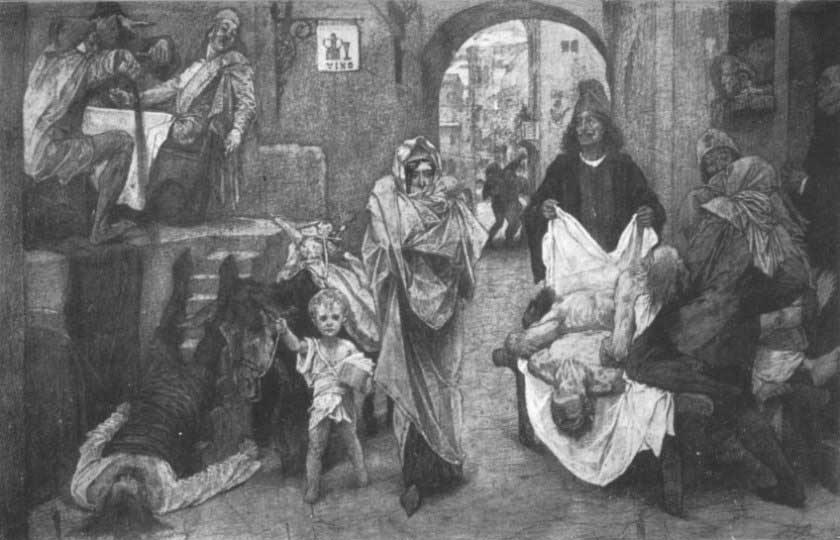

In 1848 he went to Brussels, and worked there for a[Pg 7] time without any master, painting the first picture that deserves to be remembered. Characteristically enough, this depicted Cimabue finding Giotto in the fields of Florence. The shepherd boy is engaged in drawing the figure of a lamb upon a smooth rock, using a piece of coal for pencil; an admirable and precocious piece of work. At the time it was first shown it was considered especially good in its harmonious and original colouring, nor did a sight of it in 1896 at the Winter Exhibition of the Royal Academy contradict the generous verdict of contemporary critics. At Brussels he painted a portrait of himself, a notable thing of its kind, wherein we see a slight, dark youth, with a face of much charm and distinction, whose features one easily sees to be like those of later portraits. Then, immediately before the return to Frankfort, and the studying there, under Steinle, Leighton spent some months in Paris, working in an atelier in the Rue Richer. The conditions of this most informal of life-schools were such as Henri Murger, who was alive and writing at the time, might have approved, but were hardly to be called educative in any higher sense. The only master that these Bohemians could boast was a very invertebrate old artist, who seems to have been the soul of politeness and irresponsibility, and who accompanied every weak criticism with the deprecatory conclusion, "Voilà mon opinion!" "M. Voilà mon opinion!" is a type not unknown otherwhere than in that Paris atelier. A fine alterative the student must have found the severe and stringent tonics that Steinle prescribed immediately afterwards in Frankfort. In the admirable monograph on "Sir Frederic Leighton" by Mrs. Andrew Lang, from which we have drawn on occasion in these pages, an interesting account[Pg 8] is given of an exploit at Darmstadt, in which the young artist took a chief part. An artists' festival was to be held there, and Sir Frederic and one of his fellow-students, Signor Gamba, took it into their heads to paint a picture for the occasion on the walls of an old ruined castle near the town. The design was speedily sketched after the most approved mediæval fashion, and no time was lost in executing the work. "The subject was a knight standing on the threshold of the castle, welcoming the guests, while in the centre of the picture was Spring, receiving the representatives of the three arts, all of them caricatures of well-known figures. In one corner were the two young artists themselves, surveying the pageant. The Schloss where this piece was painted is still in existence, and the Grand Duke has lately erected a wooden roof over the painting, to preserve it from destruction." Before leaving Frankfort, Leighton had already interested Steinle in his projected picture of Cimabue's Madonna, and the design for it was made under Steinle's direction. Under his direct influence, too, and inspired by Boccaccio, another Florentine picture—a cartoon of its great plague—was painted. In speaking of the dramatic treatment of its subject, Mrs. Lang describes "the contrast between the merry revellers on one side of the picture and the death-cart and its pile of corpses on the other, while in the centre is the link between the two—a terror-stricken woman attempting to escape with her baby from the pestilence-stricken city. We shall look in vain among the President's later works for any picture with a similar motif. In general he shared Plato's opinion—that violent passions are unsuitable subjects for art; not so much because the sight of them is degrading, as because what is at once hideous and transitory in its nature should not be perpetuated."

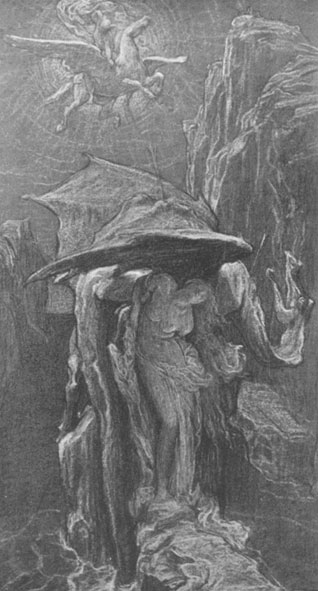

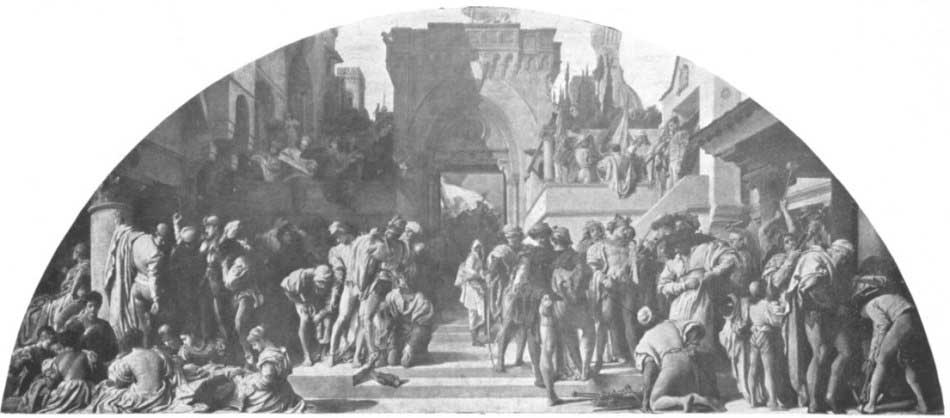

SCHEME FOR A PICTURE: THE PLAGUE IN FLORENCE

[Pg 9]We have seen how the spirit and sentiment of Italy continually remained by the artist in his German studio, and how in Frankfort his artistic imagination returned again and again to Florence, and to the early Florentines of his particular adoration—Cimabue and Giotto. The recall to Italy came inevitably, as Steinle's teaching at last had fully worked its purpose. Steinle himself counselled the move, and gave his favourite pupil an introduction to Cornelius in Rome. It was to Rome, therefore, and not to Florence, that the young artist went—to Rome where sooner or later the steps of all men who work for art or for religion tend, and where so few stay. This was in 1852, the year which was represented in the Commemorative Exhibition at Burlington House by A Persian Pedlar, a small full-length figure of a man in Oriental costume, seated cross-legged on a divan, with a long pipe in his hand. To 1853 belongs a Portrait of Miss Laing (Lady Nias), which was shown again at the same time. The Rome of the mid-century was Rome at its best, with much artistic stimulus of the present, as well as of the past. The English colony was particularly strong. Thackeray was there, moving about after his wont in the studios and salons; the Brownings were there, and in their prime. The young painter and his work, including the Cimabue's Madonna in its earlier stages, made a great impression on Thackeray, who turned prophet for once on the strength of it. On returning to London and meeting Millais, he prophesied gaily to that ardent Pre-Raphaelite, then marching on from success to success: "Millais! my boy, I have met in Rome a versatile young dog called Leighton, who will one of these days run you hard for the presidentship!" This was early days for such a rumour to reach the Academy, who knew an older[Pg 10] school, represented by Landseer and Eastlake, and a younger school, represented by Millais and Rossetti, but as yet knew not Leighton. Among the leading artists in Rome at this time, beside Cornelius, were the two French painters, Bouguereau and Gerome. To these, especially to Bouguereau, who was a great believer in "scientific composition," Leighton was, on his own testimony, largely indebted for his fine sense of form. Yet another famous Frenchman, Robert Fleury, whom he afterwards met in Paris, may be mentioned here, since from him he learnt much in the way of colouring, and the technique of his art. Turning from the painters to the poets, it was at Rome that Robert Browning, who was at this time writing his "Men and Women," formed close acquaintance with the young artist. Something of the atmosphere which permeates such poems as "Bishop Blougram's Apology," "Andrea del Sarto," and others of the same series, seems to linger yet in the record of those early meetings of poets and painters, with all their associations:

"The Vatican,

Greek busts, Venetian paintings, Roman walls, And English books."

One easily supposes Browning speaking through his Bishop Blougram, as, it is said, he was heard to speak in those days in praise of Correggio, to whose qualities, Ruskin tells us, Sir Frederic Leighton curiously approximates:

"'Twere pleasant could Correggio's fleeting glow

Hang full in face of one where'er one roams, Since he more than the others brings with him Italy's self—the marvellous Modenese!" Italy's self, in truth, Frederic Leighton, like Browning in[Pg 11] poetry, did not fail to bring with him, and revived for us for many years, by his art and southern glow of colour, in the gray heart of London.

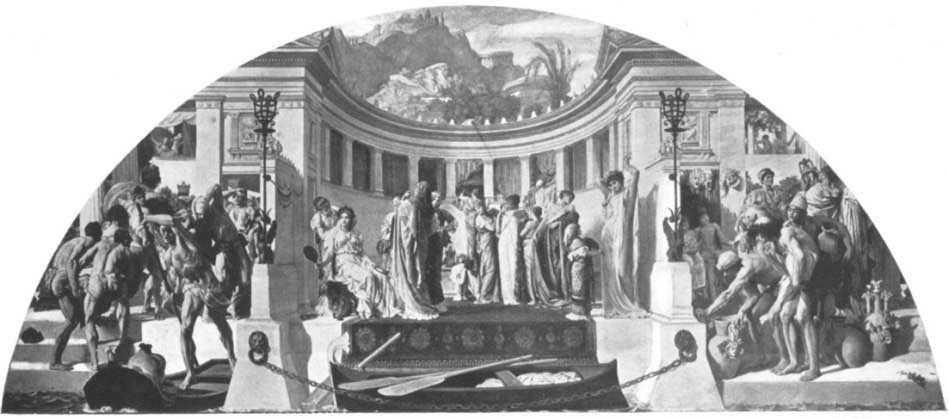

CIMABUE'S MADONNA CARRIED IN PROCESSION THROUGH THE STREETS OF FLORENCE (1855)

Among other people whom Leighton met in Rome were George Sand, Mrs. Kemble, George Mason the painter, of Harvest Moon fame, Gibson the sculptor, and Lord Lyons. Like Robert Browning, let us add, he was readily responsive to the quickening of his contemporaries, and vigorously studied the present in order that he might the better paint the past, and put live souls into the archaic raiment of Cimabue and old Florence. He was working hard all this while, with a devotion and concentration that impressed other friends beside Thackeray, upon his picture of Cimabue's Madonna, which was exhibited in the Academy of 1855, and as the work of an unknown hand made a distinct sensation. It was discussed, angrily by some, delightedly by others. The criticism which Rossetti, Mr. Ruskin, and other critics bestowed upon it in the press or in private correspondence[1] will come more fitly into our later pages, when we turn to deal with contemporary opinions upon Leighton's work. Enough to say here that it won fame for the artist at a stroke. The Queen bought it for £600, having bespoken it, I believe, before it left his studio, and hung it eventually in Buckingham Palace. With this encouraging first great success, the probationary stage of our artist's history may be said to close.

CHAPTER IIYear by Year—1855 to 1864The Academy of forty years ago was very different from that we know to-day. It was held in the left wing of the National Gallery, and had not nearly so much space at its disposal as it has in its present quarters at Burlington House. The exhibition of 1855 contained few pictures, compared with the multitudinous items of the present shows. Generally speaking, the exhibition was of a heavier, more Georgian aspect, in spite of certain Pre-Raphaelite experiments and other signs of the coming of a younger generation. Sir Charles Eastlake was President. Professor Hart was delivering lectures to its students, full of academic, respectable intelligence, if little more; lectures which those who are curious may find reported in full in the "Athenæum" of that time. More interesting was the appearance of Mr. Ruskin as commentator on the pictures of the Academy in this year, the first in which he issued his characteristic "Academy Notes." His long, and, all things considered, remarkably appreciative criticism of the Cimabue's Madonna we discuss elsewhere (p. 103). Of another picture of Italy by a very different painter, which was considered a masterpiece by some critics, we find him speaking in terms of monition: "Is it altogether too late to warn him that he is fast becoming nothing more than an Academician?"[Pg 13] The one picture of the year, according to Mr. Ruskin, was the Rescue, by Millais. "It is the only great picture exhibited this year," he writes, "but this is very great." For the rest, A Scene from As You Like It, by Maclise; another Shakespearean subject, the inevitable Lear and Cordelia, by Herbert; and a Beatrice by the then President, and we have recalled everything that served to give the Academy of that year its distinction in the eyes of contemporary critics. Sir Edwin Landseer, who to the outer world was the one great fact in the art of the time, does not appear to have exhibited in 1855. Looking back now to that date, what one discerns chiefly is the emergence of the Pre-Raphaelites from the more conventional multitude that were taking up the artistic traditions of the first half of the century. Millais, Rossetti, Holman Hunt, and their associates, count to us, to-day, as the representatives of an earlier generation; in 1855 they still stood for all that was daring, unprecedented, and adventurous in their art. This newcomer, with his Cimabue's Madonna in a new style, puzzled the critics considerably. They did not know quite how to allot him in their casual division of contemporary schools. "Landseer and Maclise we know; and Millais and Holman Hunt; but who is Leighton?" was the tenor of their commentary. Meanwhile an event of great significance to English Art in this year was happening—an exhibition of English pictures in Paris, the first of its kind. This beginning of such international exchanges was important; it has led up to many striking modifications of both English and French schools since that date. It is curious that it should coincide with the awakening to certain other foreign influences: that of the early Italian school upon the Pre-Raphaelites, and that of the later Italian, popularly[Pg 14] known as "the classic school," upon Leighton and Mr. G. F. Watts. Of this exhibition of English pictures, which was held in the Avenue Montaigne, M. Ernest Chesneau, a critic very sympathetic to English art, tells us, in his admirable book on the "English School of Painting," that "for the French it was a revelation of a style and a school of the very existence of which they had hitherto had no idea; and whether owing to its novelty, or the surprise it occasioned, or, indeed, to its real merit, whatever may have been the true cause, most certain it is that the English, until then little thought of and almost unknown abroad, obtained in France a great success." M. Chesneau, in going on to account further for the great impression made by the English painters in Paris, attributes it largely to the singularity which, for foreign eyes, marks their work. It is curious, indeed, that French critics, and M. Chesneau among them, really admire this singularity, which they count distinctively British. They look for it in our pictures, and if they do not find it—as in the work of Leighton—they feel aggrieved. British eccentricity, whether thinking its way with the aid of genius into "Pre-Raphaelitism," or now again, with the aid of extreme cleverness and talent, into certain cruder forms of "impressionism," is sure of its effect. But an art like Leighton's, whose aim is beauty and not eccentricity, is apt to be slighted by both French and English critics, with some notable exceptions. Not all its grace, its classic quality, its beauty of line and distinction of treatment, avail it, when it comes into conflict with doctrinaire theories on the one hand, and a love for mere sensationalism on the other.

THE DEAD ROMEO

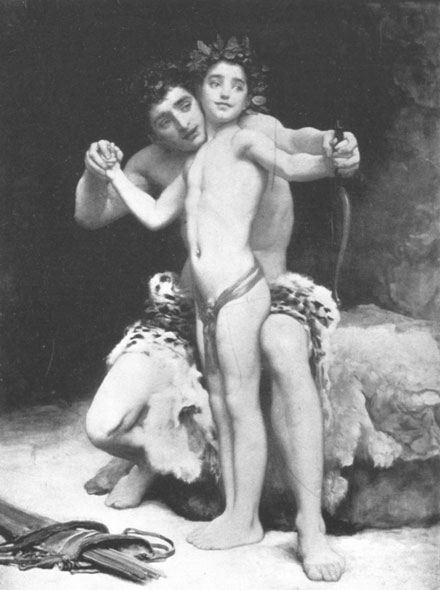

The success of his picture at the Academy, and the[Pg 15] incidental lionizing of a season, did not tempt the artist to stay long in London, and he went to Paris, where he settled himself in a studio and proceeded to complete his Triumph of Music, and other pictures begun in Rome. By this time the painter's method might seem assured, but Paris was still able to add something to his style, with the aid of such masters as Fleury. English critics, who expected The Triumph of Music to sustain the reputation won by Cimabue's Madonna, were disappointed—partly because Orpheus was represented as playing a violin, in place of the traditional lyre. To those who will examine and compare them more carefully, there is no such discrepancy. The Triumph of Music: Orpheus by the power of his Art redeems his wife from Hades, which is every whit as distinctive a performance as the Cimabue's Madonna (as indeed it was conceived and painted largely under the same conditions), was nevertheless not a popular success. Certainly, it marks, as clearly as anything can, the sense of colour, the sense of form, the draughtsmanship, the immensely cultured eye and hand, first discovered to the English critics by its predecessor. It was sold after the painter's death. Of certain other works painted in 1856, 1857, and 1858, some of which never found their way to the Academy, little need be said. To this period belong two pictures painted in Paris, the one, Pan under a fig-tree, with a quotation from Keats's "Endymion":

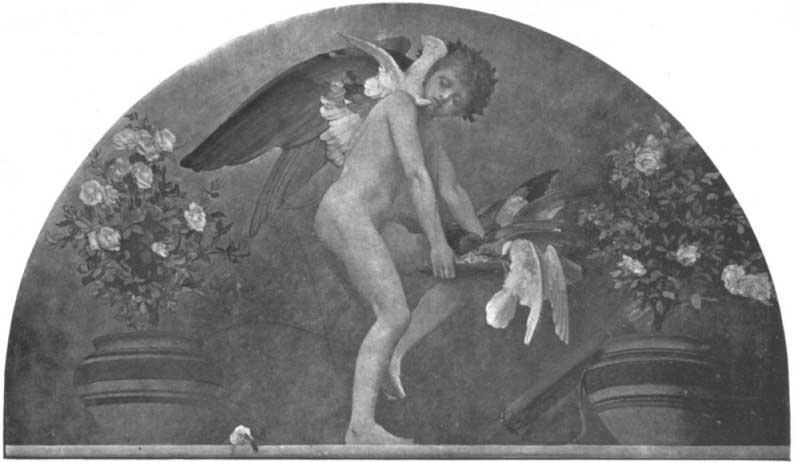

"O thou, to whom

Broad-leaved fig-trees even now foredoom Their ripened heritage," and the other, a pendant to it, A Nymph and Cupid. Salome, the Daughter of Herodias, painted in 1857,[Pg 16] but apparently not exhibited at the Academy, represents a small full-length figure in white drapery, with her arms above her head, which is crowned with flowers; behind her stands a female musician. Another, shown in 1858 at the Royal Academy, and again in the 1897 retrospective exhibition, was first entitled The Fisherman and Syren, and afterwards The Mermaid; it is a composition of two small full-length figures, a mermaid clasping a fisherman round the neck. The subject is taken from a ballad by Goethe:

"Half drew she him,

Half sunk he in, And never more was seen." In the same year was a painting inspired by "Romeo and Juliet," entitled Count Paris, accompanied by Friar Laurence, comes to the house of the Capulets to claim his bride; he finds Juliet stretched, apparently lifeless, on the bed. The picture shows, in addition to the figures named in its former title, the father and mother of Juliet bending over their daughter's body, and through an opening beyond numerous figures at the foot of the staircase. The latter year marked the painter's return to London, where he entered more actively into its artistic life than he had done hitherto, and made closer acquaintance with the Pre-Raphaelites, who were already entering upon their second and maturer stage. To take Rossetti: it was in 1856 that he made those five notable designs to illustrate "Poems by Alfred Tennyson," which Moxon and Co. published in the following year; an event that, for the first time, really introduced him to the public at large. To 1857, again, belongs Rossetti's Blue Closet and Damsel of the Sangrael, both painted for Mr. W.[Pg 17] Morris. And in 1857 and 1858, the famous and hapless distemper pictures on the walls of the Union Debating Society's room at Oxford, were engaging Rossetti and his associates, including Burne-Jones, William Morris, Mr. Val. Prinsep, Mr. Arthur Hughes, and Mr. Spencer Stanhope.

A PENCIL STUDY

It was in the summer of 1858, Mr. F. G. Stephens tells us, that the original Hogarth Club was founded, of which the two Rossettis were prominent instigators,—one of the most notable of the many protestant societies that have sprung up at different times from a slightly anti-Academic bias. It is interesting to find that Leighton's famous Lemon Tree drawing in silverpoint was exhibited here. The Hogarth Club held its meetings at 178, Piccadilly, in the first instance; removed afterwards to 6, Waterloo Place, Pall Mall, and finally dissolved, in 1861, after existing for four seasons. To speak of other painters more or less associated with Rossetti and his school, Mr. Holman Hunt, whose Light of the World had greatly struck Paris in 1855, exhibited his Scapegoat at the Academy of 1856, a picture which called from Mr. Ruskin immense praise, and a characteristic protest: "I pray him to paint a few pictures with less feeling in them, and more handling." Of Millais we have already spoken. In 1856 he exhibited The Child of the Regiment, Peace Concluded, and Autumn Leaves. In 1859 Leighton showed three pictures at the Academy. One, A Roman Lady (then called La Nanna), a half-length black-haired figure, facing the spectator, in Italian costume; another, now called Nanna, then entitled Pavonia, a half-length figure of a girl in Italian costume, with peacock's feathers in the background; and Sunny Hours, which seems to have escaped record so far. The[Pg 18] same year saw another of his pictures, Samson and Delilah, exhibited at Suffolk Street. We must not pass by the famous Study of a Lemon Tree (now at Oxford), mentioned above, without quoting the praise by Mr. Ruskin, which made it famous. Mr. Ruskin couples it with another drawing, both of which we have been fortunately able to reproduce in our pages. These "two perfect early drawings," he writes, "are of A Lemon Tree, and another of the same date, of A Byzantine Well, which determine for you without appeal, the question respecting necessity of delineation as the first skill of a painter. Of all our present masters Sir Frederic Leighton delights most in softly-blended colours, and his ideal of beauty is more nearly that of Correggio than any seen since Correggio's time. But you see by what precision of terminal outline he at first restrained, and exalted, his gift of beautiful vaghezza." The Lemon Tree study, let us add, was drawn at Capri in the spring of 1859. Here, and elsewhere in the South of Europe, whither the artist returned, escaping from London at every opportunity, many other notable studies and drawings were made during this period. Some of these were employed long since for the backgrounds of pictures familiar to us all. Others, faithful studies of nature, small oil and water-colour drawings, chiefly landscape, were scarce known to the general public during the painter's life, but were eagerly competed for at the sale of his pictures in July, 1896. The little picture of Capri at Sunrise was hung in the Academy of 1860, the painter's only contribution of that year. In the year following, we find another small picture of Capri, together with five others, some of which played their part in winning for the artist his wider recognition.

A LEMON TREE

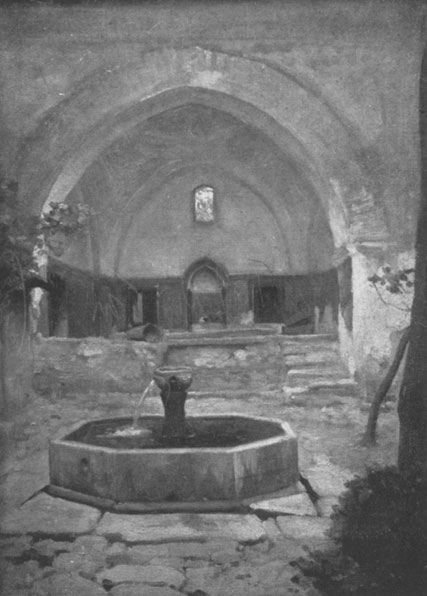

BYZANTINE WELL HEAD

[Pg 19]Meanwhile, the artist was drawing his London ties closer. In 1860 he took up his abode at 2, Orme Square, where he continued to reside until he built his famous house in Holland Park Road, some years later. His art did not for this reason become more like London, or more infected with that British singularity which some critics would seem to demand. On the contrary, Italy and the South, the glow of colour, the perfection of form, the plastic exquisiteness, which mark for us his mature performances, and which follow after classic ideals, were more and more clearly to be discerned in the remarkable cycle of pictures associated with this part of his career. In 1861 he painted portraits of his sister, Mrs. Sutherland Orr, and of Mr. John Hanson Walker, the former shown at the Academy, where also hung Paolo e Francesca, A Dream, Lieder ohne Worte, J. A.—a Study, and Capri—Paganos. Rossetti, writing of this exhibition, says: "Leighton might, as you say, have made a burst had not his pictures been ill-placed mostly—indeed, one of them (the only very good one, Lieder ohne Worte) is the only instance of very striking unfairness in the place."[2] In 1862 there were no fewer than six of the artist's pictures at the May exhibition of the Academy: the Odalisque, a very popular work, shows a draped female figure, in a very Leightonesque pose, with her arm above her head, leaning against a wall by the water. She holds a peacock's feather screen in her left hand, while a swan in the water at her feet cranes its head upwards towards her; Michael Angelo nursing his dying Servant, a group of two three-quarter length figures; the servant reclining in an armchair with his head resting against the shoulder of Michael Angelo—a fairly powerful but somewhat[Pg 20] academic version of the incident—which looks at first glance like the work of a not very important "old master;" The Star of Bethlehem, showing one of the Magi on the terrace of his house looking at the strange star in the East, while below are indications of a revel he has just left. Duett, Sisters, Sea Echoes, and Rustic Music, also belong to this year. In 1863 he showed Eucharis, a half-length figure of a white-robed girl, with a basket of fruit on her head; Jezebel and Ahab; A Cross-bow Man; and A Girl Feeding Peacocks; with these we complete the list of his work as an outsider.

GOLDEN HOURS (1864)

CHAPTER IIIYear by Year—1864 to 1869In 1864 Leighton was made an Associate of the Royal Academy. To its summer exhibition he contributed three pictures, showing great and various power in their composition. Dante at Verona, Orpheus and Eurydice, and Golden Hours. The first of these, one of the most remarkable pictures of our modern English school, in which "Dante" appears, is a large work, with figures something less than life-size. It illustrates the verses in the "Paradiso":

"Thou shalt prove

How salt the savour is of others' bread; How hard the passage, to descend and climb By others' stairs. But that shall gall thee most Will be the worthless and vile company With whom thou must be thrown into the straits, For all ungrateful, impious all and mad Shall turn against thee."

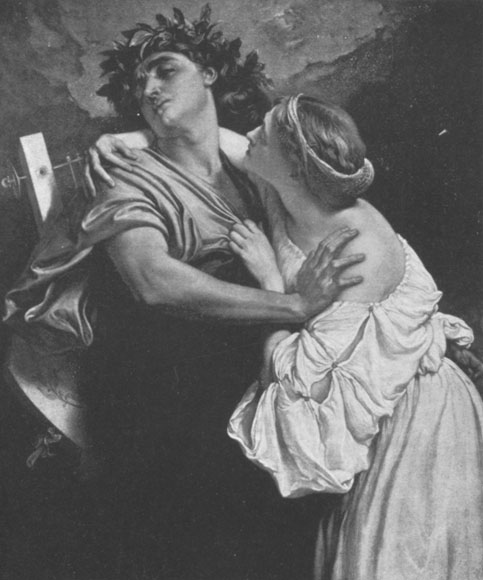

"Dante, in fulfilment of this prophecy, is seen descending the palace stairs of the Can Grande, at Verona, during his exile. He is dressed in sober grey and drab clothes, and contrasts strongly in his ascetic and suffering aspect with the gay revellers about him. The people are preparing for a festival, and splendidly and fantastically robed, some bringing wreaths of flowers. Bowing with mock reverence, a jester gibes at Dante. An indolent[Pg 22] sentinel is seated at the porch, and looks on unconcernedly, his spear lying across his breast. A young man, probably acquainted with the writing of Dante, sympathises with him. In the centre and just before the feet of Dante, is a beautiful child, brilliantly dressed and crowned with flowers, and dragging along the floor a garland of bay leaves and flowers, while looking earnestly and innocently in the poet's face. Next come a pair of lovers, the lady looking at Dante with attention, the man heedless. The last wears a vest embroidered with eyes like those in a peacock's tail. A priest and a noble descend the stairs behind, jeering at Dante."[3] It was the Golden Hours which, though perhaps less memorable and imaginative than the others, won the greatest popular success of the three, a success beyond anything that the artist had so far painted. As this picture is here reproduced, description is needless, except so far as regards the colour of the background, which is literally golden. The dress of the lady who leans upon the spinet is white, embroidered with flowers. The Orpheus and Eurydice showed that the old friendship, formed originally in Rome, between the painter and Robert Browning, was maintained. Some of the poet's lines served as a text for the picture; and as they are little known we repeat them here:

"But give them me—the mouth, the eyes, the brow—

Let them once more absorb me! One look now Will lap me round for ever, not to pass Out of its light, though darkness lie beyond. Hold me but safe again within the bond Of one immortal look! All woe that was, Forgotten, and all terror that may be, Defied,—no past is mine, no future! look at me!"

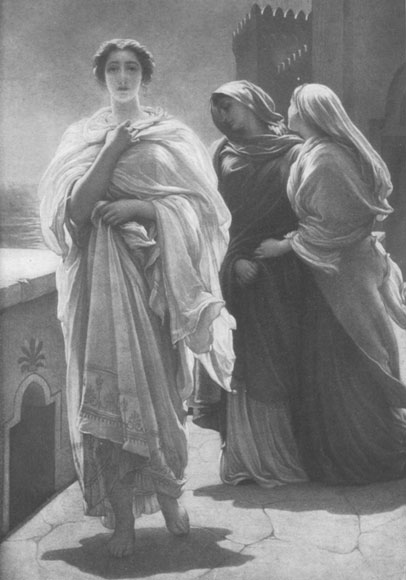

HELEN OF TROY (1865)

ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE (1864)

[Pg 23]To this year, also, belongs a portrait of The late Miss Lavinia I'Anson, a circular panel showing the sky for background. This was exhibited again in the winter Academy of 1897. In 1865 the artist showed once again his eclectic sympathies, by the variety of the subject-pictures that he sent to the Academy, ranging from David to Helen of Troy. In his tenderly conceived David, the Psalmist is seen gazing at two doves in the sky above; he, sunk in a profound reverie, is seated upon a house-top overlooking some neighbouring hills. The whole is large in its handling and treatment, and in the simplicity of its drapery recalls several of the famous illustrations the artist contributed to Dalziel's Bible Gallery. It was exhibited with the quotation, "Oh, that I had wings like a dove! for then would I fly away and be at rest." With the delightful Helen of Troy we are recalled to the third book of the Iliad, when Iris bids Helen go and see the general truce made pending the duel between Paris and Menelaus, of which she is to be the prize. So Helen, having summoned her maids and "shadowed her graces with white veils," rose and passed along the ramparts of Troy. In the picture the light falls on her shoulders and her hair, while her face and the whole of the front of her form are shadowed over, with somewhat mystical effect. To the same year belongs In St. Mark's, a picture of a lady with a child in her arms leaving the church, a lovely and finished study of colour; The Widow's Prayer; and Mother and Child, a graceful reminder of a gentler world than Helen's. In 1866 the critics had at last a work which seemed to them to follow the lines of the Cimabue's Madonna. This was the radiant and lovely picture of the Syracusan[Pg 24] Bride leading Wild Beasts in Procession to the Temple of Diana. The composition of this remarkable painting deserves to be closely studied, for it is very characteristic of Sir Frederic Leighton's theories of art, and his conviction of the necessarily decorative effect of such works. A terrace of white marble, whose line is reflected and repeated by the line of white clouds in the sky painting above, affords the figures of the procession a delightful setting. The Syracusan bride leads a lioness, and these are followed by a train of maidens and wild beasts, the last reduced to a pictorial seemliness and decorative calm, very fortunate under the circumstances. The procession is seen approaching the door of the temple, and a statue of Diana serves as a last note in the ideal harmonies of form and colour to which the whole is attuned. As compared with the Cimabue's Madonna, it is a more finished piece of work, and the handling throughout is more assured. It was as much an advance, technically, upon that, as the Daphnephoria, which crowned the artist's third decade, was upon this. According to popular report, it was this picture of the Syracusan Bride which decided his future election as a full member of the Academy; but as a matter of fact, it was in 1869 that this election took place. The picture, let us add, was suggested to the painter by a passage in the second Idyll of Theocritus: "And for her then many other wild beasts were going in procession round about, and among them a lioness." The Painter's Honeymoon and a Portrait of Mrs. James Guthrie were also exhibited this year; and the wall-painting of The Wise and Foolish Virgins, at Lyndhurst, in the New Forest, was executed during the summer.

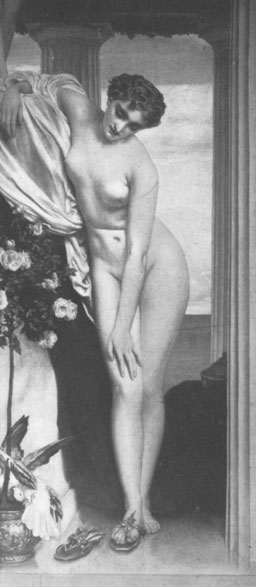

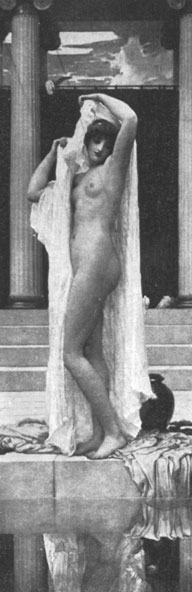

VENUS DISROBING FOR THE BATH (1867)

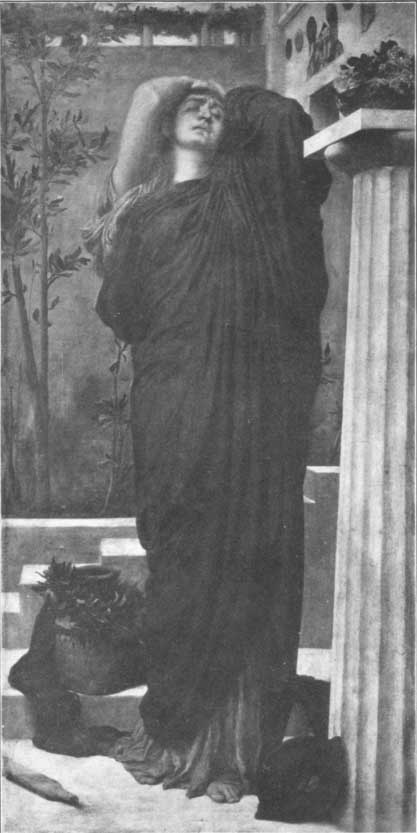

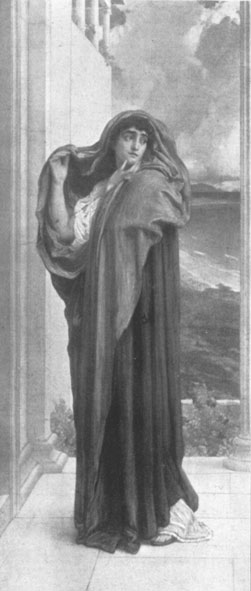

ELECTRA AT THE TOMB OF AGAMEMNON (1869)

In its next exhibition, that of 1867, the Academy held five pictures by the artist, including the delightful[Pg 25] Pastoral, two small full-length figures standing in a landscape of a shepherd and a girl—whom he is teaching to play the pipes. This again might be considered a painter's translation from Theocritus, and the Venus Disrobing for the Bath, one of the most debated of all the artist's paintings of the nude. The paleness of the flesh-tint of this Venus aroused a criticism which has often been urged against his pictures—that such a hue was not in nature. In imparting an ideal effect to an ideal subject, Leighton always, however, followed his own conviction—that art has a law of its own, and a harmony of colour and form, derived and selected no doubt from natural loveliness, but not to be referred too closely to the natural, or to the average, in these things. To the 1868 Academy Leighton contributed another biblical theme, Jonathan's Token to David. With this were four others, as widely varying in subject and conception as need be desired. One was a very charming portrait of a very pretty woman, Mrs. Frederick P. Cockerell. Then follow three more in that cycle of classic subjects, of which the painter never tired. The full title of the first runs, Ariadne abandoned by Theseus: Ariadne watches for his return: Artemis releases her by death. In it the figure of Ariadne, clothed in white drapery, is seen lying on a rocky promontory overlooking the sea. Acme and Septimius is a circular picture, with two small full-length figures reclining on a marble bench. This extract from Sir Theodore Martin's translation of Catullus was appended to its title in the catalogue:

"Then bending gently back her head,

With that sweet mouth so rosy red, Upon his eyes she dropped a kiss, Intoxicating him with bliss." [Pg 26]A love song on canvas, a pictorial transcript from Catullus, it was perhaps the most popular picture of the year. The last of the three was Actæa, the Nymph of the Shore. It represents a small full-length nude figure lying on white drapery by the sea-shore. Actæa is a lovely figure, full of that grace which Leighton so well knew how to impart to his idealized figures. After this year, at any rate, there could be no longer any doubt but that the artist's power really lay in the creation of ideal forms; whether presented in monomime or combined in poetic and decorative groups, called up from the wonderful limbo of classic myth and history. With 1869 came Electra at the Tomb of Agamemnon, a memorable picture, full of characteristic effects of colour and composition, and a notable exercise in the grand style. This work, considered from any side, must be seen to be the outcome of a unique faculty, so unprecedented in English art as to run every risk of misconception that native predilections could impose upon those who stopped to criticise it. The figure of Electra clad in black drapery offered a problem of peculiar difficulty. Another painting shown this year was Dædalus and Icarus, a strikingly conceived picture. The two figures are singularly noble conceptions of the idealized nude; the drapery at the back of Icarus is typical of the painter in every fold, while the landscape seen far below the stone platform on which the figures stand, shows a bay of the blue Ægean sea in full sidelight, with a lovely glimpse of the white walls of a distant town. The same exhibition of 1869 saw, also, the vigorously painted diploma picture, St. Jerome, which marked his election as R.A. In it the saint, nude to the waist, kneels with uplifted arms at the foot of a crucifix, his[Pg 27] lion seen in the background. Helios and Rhodos, another painting exhibited at the same time, shows Helios descending from his chariot, which is in a cloud above, to embrace the nymph Rhodos, who has risen from the sea.

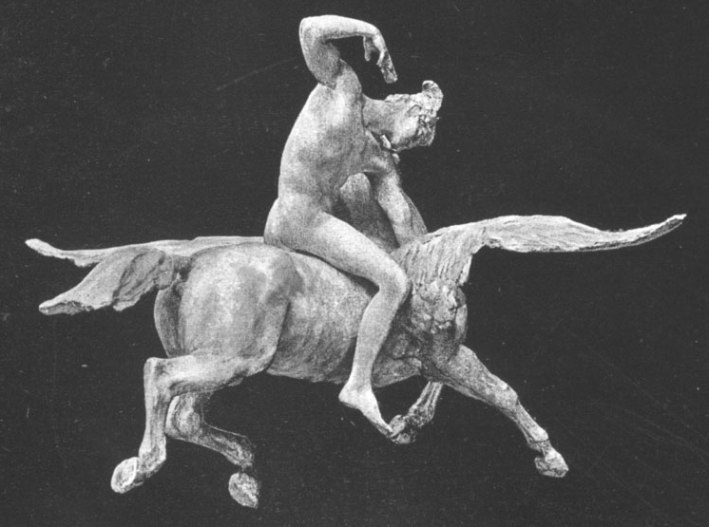

DÆDALUS AND ICARUS (1869)

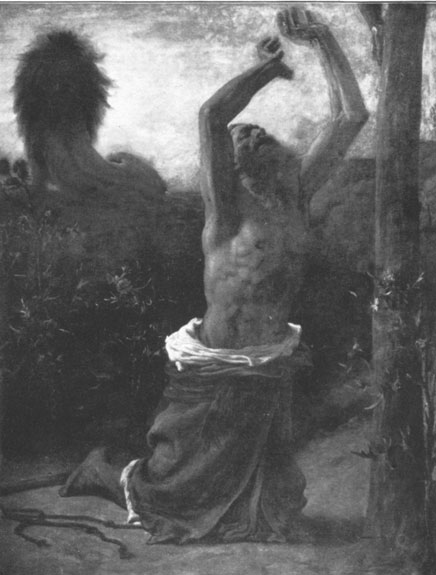

ST. JEROME (1869)

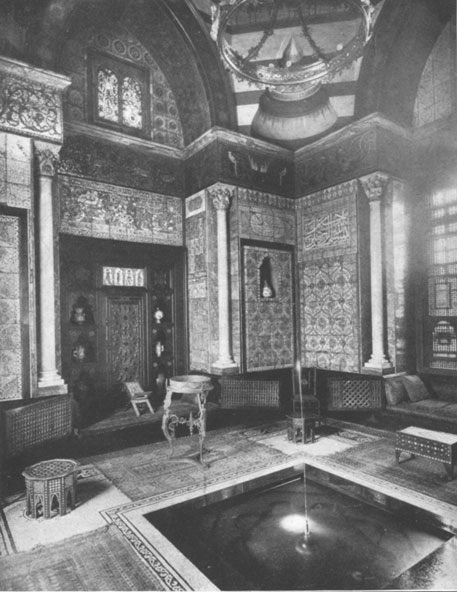

CHAPTER IVYear by Year—1870 to 1878Sundry journeys into the East during this period of Leighton's career, gave him new subject-matter, new tints to his palette, and added something of an oriental fantasy to the classic sentiment of his art. The sketches of Damascus and other time-honoured eastern cities, mosques, gardens, and courtyards, which figured largely among Sir Frederic's studies, were made for the most part in the autumn of 1873. Previously, as early as 1867, the East had cast its spell upon him. In 1868, he went into Egypt, and made a voyage up the Nile with M. de Lesseps, then at the flood of good-fortune. The Khedive himself provided the steamer for this adventure. "It was during this voyage," we are told, "that Sir Frederic came across a small child with the strangest and most limited idea of full dress that probably ever occurred to mortal—a tiny coin strung on to one of her strong coarse hairs." Of the studies made during the journey, one is a woman's head, draped so as to have a singularly archaic and Sphinx-like effect, Another is the fine profile of a young peasant; and yet another, the head of an old man, simple-minded and philosophical.

GARDEN AT GENERALIFE, GRANADA

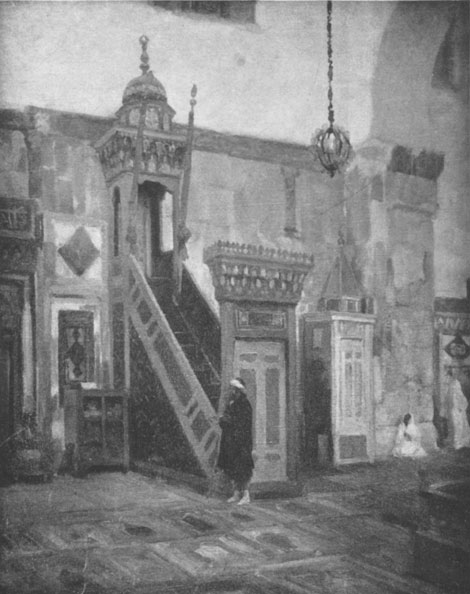

MIMBAR OF THE GREAT MOSQUE AT DAMASCUS

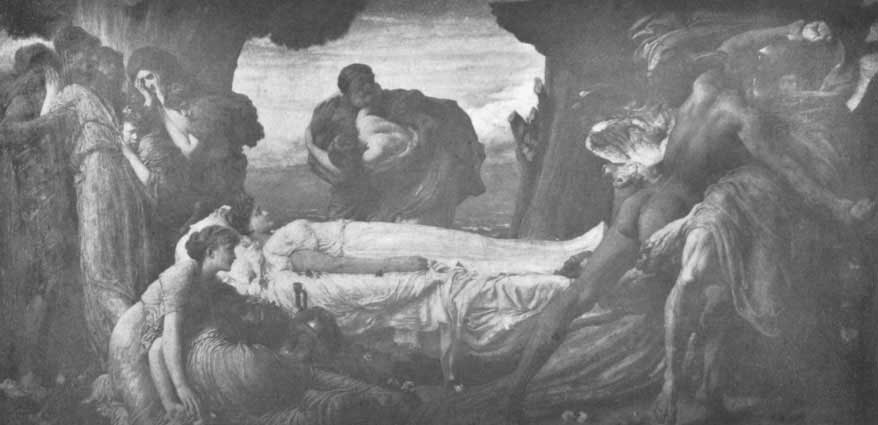

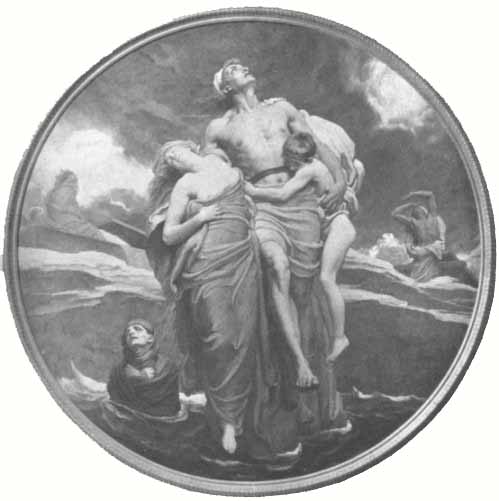

In 1869 the Helios and Rhodos, already mentioned, served as the first sign to the public of the new R.A.'s interest in things oriental. To the 1870 exhibition, his only contribution was the picture, A Nile Woman, which[Pg 29] is now owned by the Princess of Wales. It is a small full-length figure of a girl, balancing an empty pitcher upon her head, at the time of moonrise. Anticipating the Eastern subjects which future years produced, we may note a picture of Old Damascus, showing the Jews' quarter in that fabled city, in all its motley picturesqueness, and the delightful Moorish Garden,—A Dream of Granada, which were exhibited in 1874. A powerful picture, shown in 1875, of the Egyptian Slinger,[4] is illustrated later in this volume, but no reproduction can quite suggest the striking colouring of the original, and the masterly treatment of its light and shade, in the presentment of this lonely figure posed high on its platform against the clear evening sky. The delightful Little Fatima, and the Grand Mosque, Damascus, enlarged from the sketch previously alluded to, were also exhibited in 1875. But perhaps the most picturesque memorial of the East due to the artist's wanderings of these years, is an architectural, and not a pictorial one. The fame of the Arab Hall in Lord Leighton's house has reached even further than that of Little Fatima, or his painting of the Grand Mosque at Damascus. Built originally to provide a setting for some exquisite blue tiles, brought by the owner from Damascus itself, it remains the most perfect representation of an oriental interior to be found in London; but this again belongs to a later period, and we must return to the date whence this chronicle was interrupted. Before doing so, however, it may be noted that in 1870 began the famous Winter Exhibitions of Old Masters and Deceased British Artists, of which Leighton was one of the most active supporters. [Pg 30]In the May exhibition of the Royal Academy, 1871, was hung a notable canvas, Greek Girls picking up Pebbles by the Sea, described at the time as "a delightful composition, comprising figures of almost exhaustless grace, and wealth of beauty in design and colour." Another painting, also shown there, Cleoboulos instructing his daughter Cleobouline, is a charming example of its kind. The philosopher, with a scroll on his lap, sits on a cushioned bench with his young daughter by his side, his earnest action in delightful contrast with her girlish grace. But his great work in 1871 was Hercules wrestling with Death for the body of Alcestis. The scene of this profound tragedy is on the sea-shore, where the body of Alcestis, robed in white, lies under the branches of trees in the centre of the picture. On the left is a group of mourners, a seated girl and a woman prostrate in grief. On the right are the two struggling figures; Hercules' superb form and tossing lion-skin contrasting finely, both in action and colouring, with the tall and coldly grey-robed spectre of Death, who presses forward to the bed where Alcestis lies, whence he is thrust back by the mighty Hercules. The exquisite figure of Alcestis with her statuesquely draped robes and their pure and delicate colouring, forms a wonderful contrast to the two strenuous figures on the right, while the figures of the mourners on the left are delightfully posed and full of grace. In July of this year, it is interesting to remember, appeared Browning's "Balaustion's Adventure," which contained the following tribute to the above picture and its painter:

"I know, too, a great Kaunian painter, strong

As Herakles, though rosy with a robe Of grace that softens down the sinewy strength: [Pg 31]And he has made a picture of it all. There lies Alkestis dead, beneath the sun, She longed to look her last upon, beside The sea, which somehow tempts the life in us To come trip over its white waste of waves, And try escape from earth, and fleet as free. Behind the body I suppose there bends Old Pheres in his hoary impotence; And women-wailers, in a corner crouch —Four, beautiful as you four,—yes, indeed! Close, each to other, agonizing all, As fastened, in fear's rhythmic sympathy, To two contending opposite. There strains The might o' the hero 'gainst his more than match, —Death, dreadful not in thew and bone, but like The envenomed substance that exudes some dew, Whereby the merely honest flesh and blood Will fester up and run to ruin straight, Ere they can close with, clasp and overcome, The poisonous impalpability That simulates a form beneath the flow Of those grey garments; I pronounce that piece Worthy to set up in our Poikilé!"

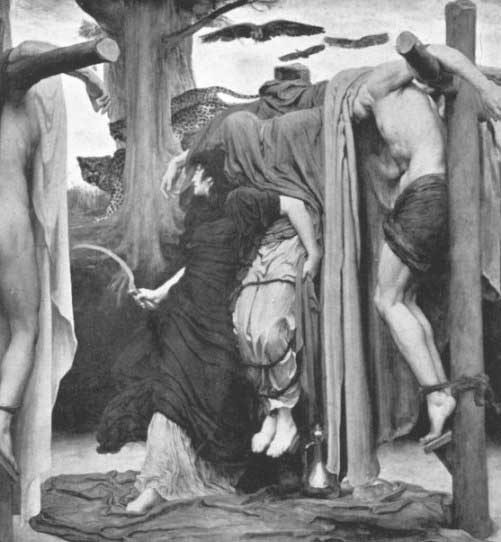

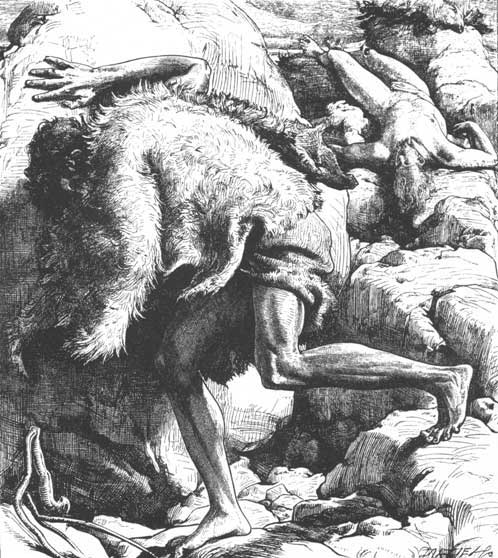

HERCULES WRESTLING WITH DEATH FOR THE BODY OF ALCESTIS (1871)

SUMMER MOON (1872)

To 1872 belongs the Summer Moon, one of the loveliest things ever shown at the Academy, a picture full of that rarer feeling for light and colour, which the artist achieved again and again in his treatment of sunset, twilight, and night effects. After Vespers, exhibited the same year, is a three-quarter length figure of a girl in a green robe standing in front of a bench, holding in her right hand a string of beads. This year's Academy held also A Condottiere, the noble figure of a man in armour, now in the Birmingham Municipal Gallery, and a portrait of the Right Hon. Edward Ryan. Hardly less memorable was Moretta, exhibited in the Academy of 1873, in the words of a critic of the day, "one of the most subtle and fortunate productions of the painter." Moretta is robed in green, with masses of loosely arranged hair, and[Pg 32] a tender and delicate face. Weaving the Wreath, shown the same year (and again in the Guildhall, 1895), is a very charming figure of quite a young girl seated on a carpet upon a raised step at the foot of a building. Behind her is a bas-relief, against which her head, crowned by a chaplet of flowers, tells out with sculpturesque effect; the sharp, vertical line of thread strained between her hands, and thence in diagonal line to the ball at her feet, is curiously rigid, and by contrast makes the draperies across which it is silhouetted appear still more mobile. We are passing over, deliberately, the artist's decorative masterpieces of this period,—the South Kensington frescoes to wit; of which the Arts of War belongs to the year 1872, and its companion, Arts of Peace, to 1873. These works will be found treated at length in a later chapter on the artist's decorative work (pp. 63, 64). In the Academy of 1874 appeared four pictures, the most important being the heroic painting,—Clytemnestra from the Battlements of Argos watches for the Beacon-fires which are to announce the Return of Agamemnon. In this picture, the figure of Clytemnestra is seen standing erect, with hands folded, supporting the drapery that clothes a majestic form. For further description, we may be content to quote that given at the time in the appreciative art columns of the "Athenæum:" "There is the grandeur of Greek tragedy in Mr. Leighton's Clytemnestra watching for the signal of her husband's return from Troy. The time is deep in the fateful night, while the city sleeps; moonlight floods the walls, the roofs, the gates, and the towers with a ghastly glare, which seems presageful, and casts shadows as dark as they are mysterious and terrible. The dense blue of the sky is dim, sad, and ominous. But the most ominous[Pg 33] and impressive element of the picture is a grim figure, the tall woman on the palace roof before us, who looks Titanic in her stateliness, and huge beyond humanity in the voluminous white drapery that wraps her limbs and bosom. Her hands are clenched and her arms thrust down straight and rigidly, each finger locked as in a struggle to strangle its fellow; the muscles swell on the bulky limbs. Drawn erect and with set features, which are so pale that the moonlight could not make them paler, the queen stares fixedly and yet eagerly into the distance, as if she had the will to look over the very edge of the world for the light to come."

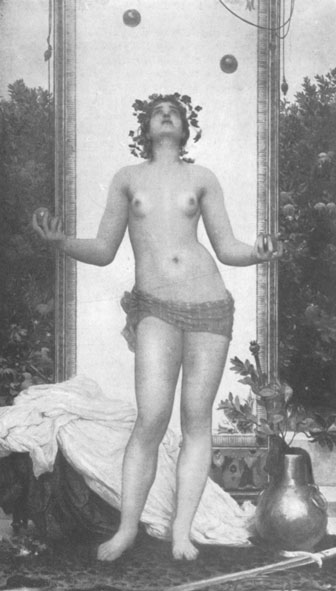

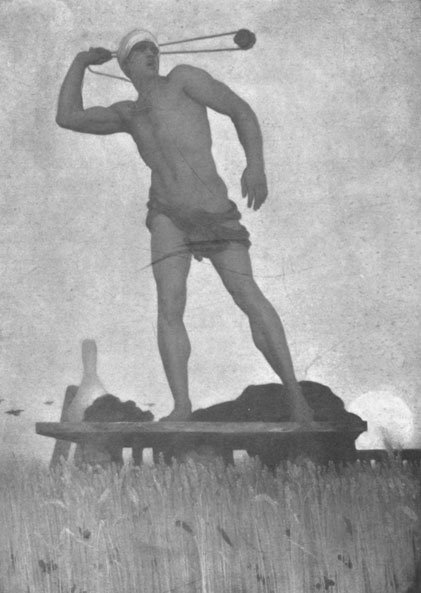

THE JUGGLING GIRL (1874)

A CONDOTTIERE (1872)

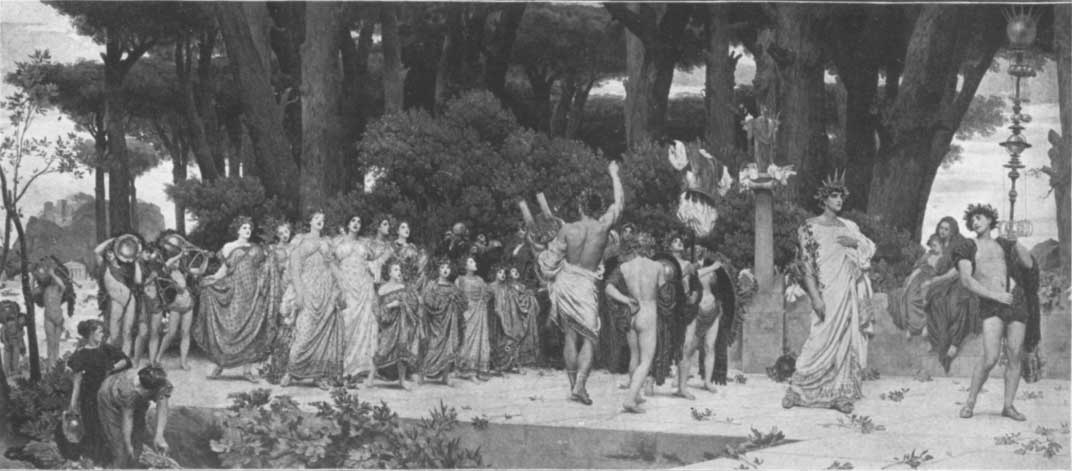

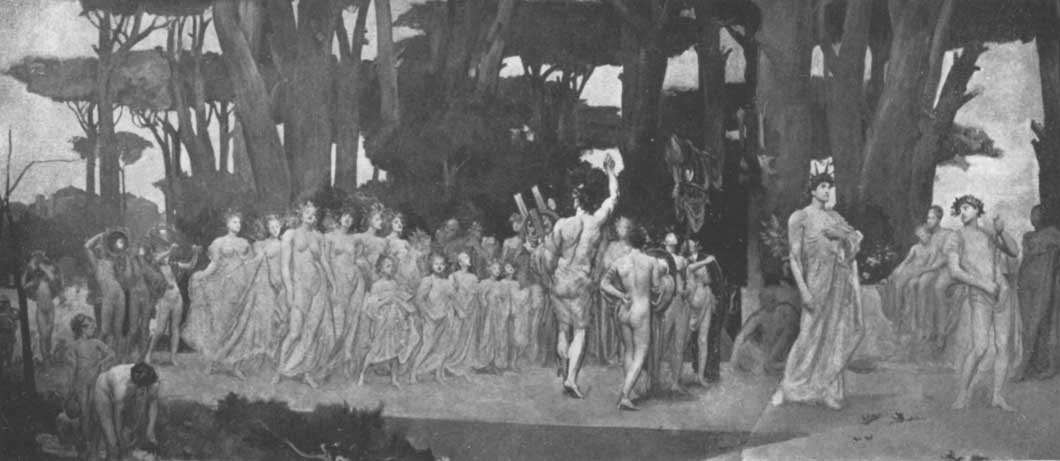

Another picture this year was the Moorish Garden—a dream of Granada, a delightful little canvas, almost square. In the foreground is a young girl carrying copper vessels, and followed by two peacocks; the background is obviously taken from the study of a garden at Generalife (reproduced at p. 28); the Antique Juggling Girl and Old Damascus: the Jews' Quarter, were also in the Academy of 1874. To 1875 belongs the Egyptian Slinger, a picture which, as we shall see later, provoked severe censure from Mr. Ruskin. As exhibited it differed much from its present state. Not only was the sky of deeper violet, but almost in silhouette against the moon, on another raised platform, stood a draped female figure, afterwards painted out entirely. Other works shown this year were Little Fatima, a small half-length figure of a little girl in Eastern costume, seen against a dark background; and a Portion of the Interior of the Grand Mosque at Damascus (reproduced at p. 28). As the building it depicts has since been burnt down, the fine transcript has an added interest. We are come now to a year which, even beyond other years of activity, displayed the artist's characteristic[Pg 34] energy: 1876. In the Academy of that year, with the Daphnephoria, Leighton once more chose a great classic theme, for a painting which, by its composition, reminded the critics and lovers of art of the artist's early triumph with the Cimabue's Madonna, and of his other great processional picture, the Syracusan Bride. Of all his works in this class, there is no doubt that the Daphnephoria is the most technically complete. The procession is seen defiling along a terrace backed by trees through which the clear southern sky gleams. A youth carrying the symbolic olive bough, called the Kopo, adorned with its curious emblems, leads the procession. He is clad in purple robes and crowned with leaves. The youthful priest, known as the Daphnephoros (the laurel-bearer) follows, clothed in white raiment. He is similarly crowned, and carries a slim laurel stem. Then come three boys, in scanty red and green draperies, which serve only to emphasize the beauty of their almost naked forms, the middle and tallest one bearing aloft a draped trophy of golden armour. These are seen to be pausing while the leader of the chorus, a tall, finely modelled man, whose back is turned, is giving directions to the chorus with uplifted right hand; in his left hand is a lyre, and the left arm from the elbow is characteristically draped. The first row of the chorus is composed of five children, clothed in purple, crowned with flowers; two rows of maidens, in blue and white, come next; and these in turn are succeeded by some boys with cymbals. The interest of the passing procession is very much enhanced by the effect produced on two lovely bystanders,—a girl and child in blue, beautifully designed, who are drawing water in the left foreground. In the valley below is seen the town of Thebes.

THE DAPHNEPHORIA (1876)

STUDY FOR "THE DAPHNEPHORIA"

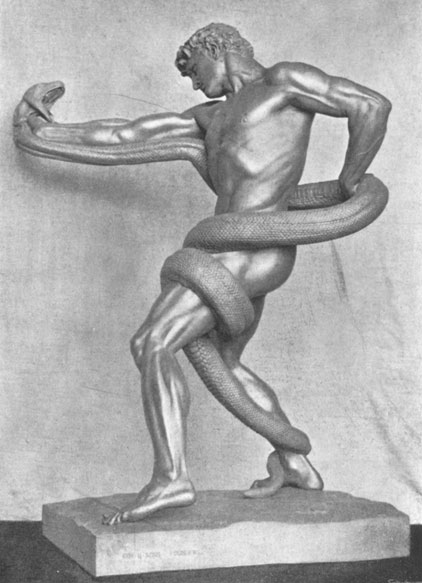

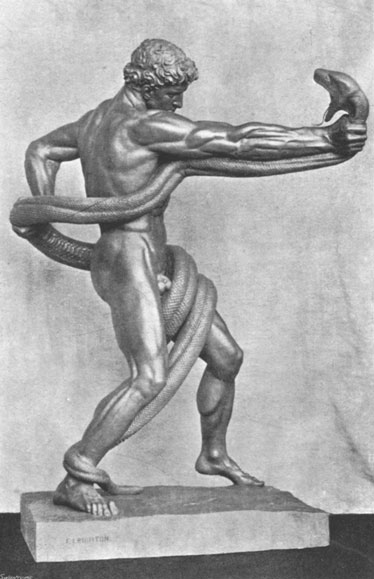

With the painter's reading of the Daphnephoria it may[Pg 35] be interesting to compare another account of this splendid religious function. At this festival in honour of Apollo, celebrated every ninth year by the Bœotians, it was usual, says pleasant Lempriere, "to adorn an olive bough with garlands of laurel and other flowers, and place on the top a brazen globe, from which were suspended smaller ones. In the middle was placed a number of crowns, and a globe of inferior size, and the bottom was adorned with a saffron-coloured garment. The globe on the top represented the Sun, or Apollo; that in the middle was an emblem of the moon, and the others of the stars. The crowns, which were 365 in number, represented the sun's annual revolution. This bough was carried in solemn procession by a beautiful youth of an illustrious family, whose parents were both living. He was dressed in rich garments which reached to the ground, his hair hung loose and dishevelled, his head was covered with a golden crown, and he wore on his feet shoes called Iphricatidæ, from Iphricates, an Athenian who first invented them. He was called Δαφνηφόρος, 'laurel-bearer,' and at that time he executed the office of priest of Apollo. He was preceded by one of his nearest relations, bearing a rod adorned with garlands, and behind him followed a train of virgins with branches in their hands. In this order the procession advanced as far as the temple of Apollo, surnamed Ismenius, where supplicatory hymns were sung to the god."[5] In the 1876 Academy hung also the striking portrait, Captain Richard Burton, H.M.'s Consul at Trieste; and two very characteristic single figures, Teresina and Paolo. The portrait of Captain Burton has been fairly described as masterly. "There is no attempt," said one critic, "at[Pg 36] posing or picturesqueness in the portrait. It is the head of a man who is lean and rugged and brown, but the face is full of character, and every line tells. It is painted in the same strong and bold, and yet careful, way that distinguishes the head of Signor Costa, painted three years later." The next year saw Leighton's first appearance as a sculptor. It was at the Academy of 1877 that he exhibited the well-known, vigorously designed and wrought Athlete Struggling with a Python.[6] This adventure of the R.A. into a new field proved so successful, that the Athlete took rank as the most striking piece of sculpture of that year. "In this work," said a friendly critic, "Mr. Leighton has attempted to succeed in a truly antique way. We are bound to admit that he has done wisely, bravely, and successfully." The statue was bought, we may add, for £2,000, as the first purchase made by the trustees of the Chantrey Fund, and is now in the Tate Gallery at Millbank. It was afterwards repeated in marble, by the artist's own hand, for the Danish Museum at Copenhagen. Still more popular was his Music Lesson, another work in the same exhibition. To realize the full charm of this picture, one must see the original; for much depends upon the beauty of its colouring. Imagine a classical marble hall, marble floor, marble walls, in black and white, and red—deep red—marble pillars; and sitting there, sumptuously attired, but bare-footed, two fair-haired girls, who serve for pupil and music-mistress. The elder is showing the younger how to finger a lyre, of exquisite design and finish; and the expression on their faces is charmingly true, while the colours that they contribute[Pg 37] to the composition,—the pale blue of the child's dress, the pale flesh tints, the pale yellow hair, and the white and gold of the elder girl's loose robe, and the rich auburn of her hair,—are most harmonious. A bit of scarlet pomegranate blossom, lying on the marble ground, gives the last high note of colour to the picture. Two other pictures of 1877 must not be omitted. Study shows us a little girl (the present Lady Orkney), in Eastern garb, diligently reading a sheet of music which lies before her on a little desk. There is great charm in the simple grace of the picture and in the softly brilliant colouring of the child's costume. Very delightful, too, is the portrait of Miss Mabel Mills (now the Hon. Mrs. Grenfell), habited in black velvet, and a large dark hat with coloured feathers, set against a grey background, a picture here reproduced. A Study, An Italian Girl, and a Portrait of H. E. Gordon, were all three shown at the Grosvenor Gallery the same year.

PORTRAIT OF THE HON. MABEL MILLS (1877)

PORTRAIT OF CAPTAIN RICHARD BURTON (1876)

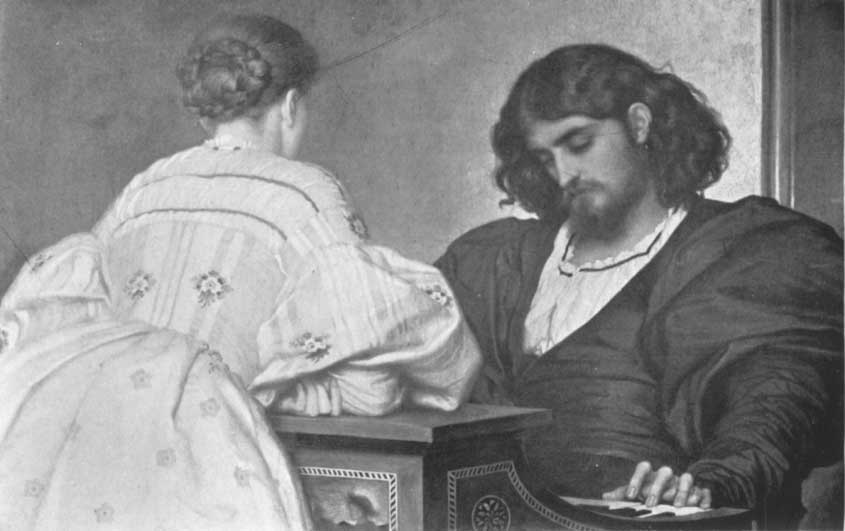

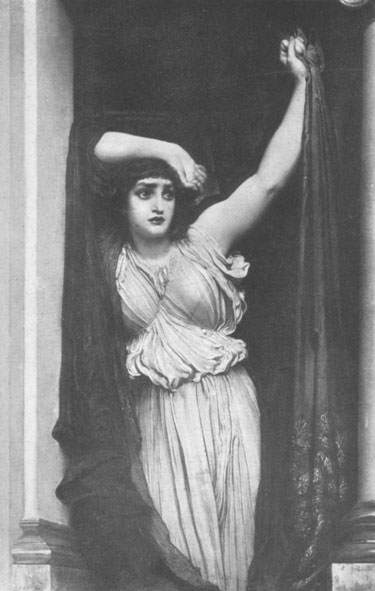

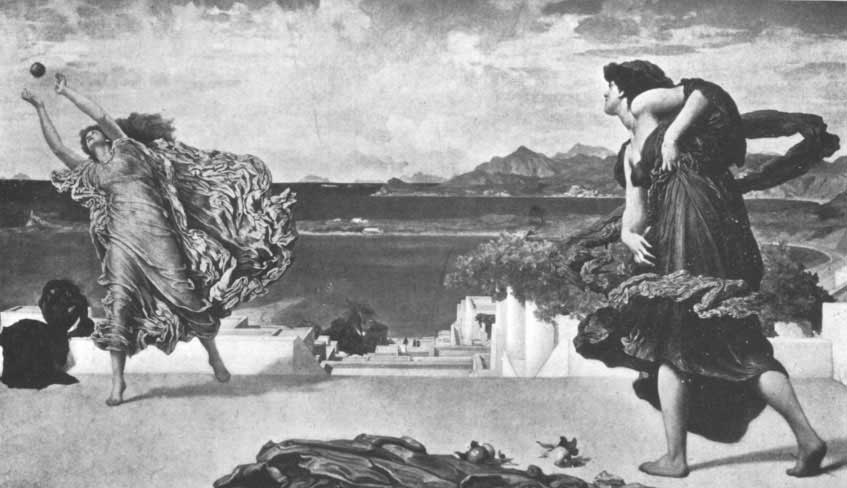

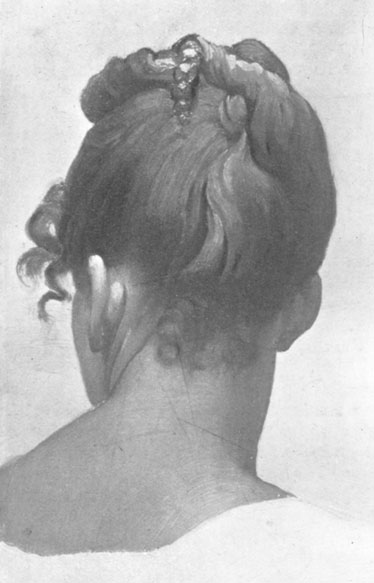

Another picture, in which a simple theme is treated in a classic fashion—not dissimilar to that employed for the Music Lesson—is Winding the Skein, a lovely painting exhibited at the Academy in 1878. In this we see two Greek maidens as naturally employed as we often see English girls in other surroundings. This idealization of a familiar occupation—so that it is lifted out of a local and casual sphere, into the permanent sphere of classic art, is characteristic of the whole of Leighton's work. He, like Sir L. Alma-Tadema and Albert Moore, contrived also to preserve a certain modern contemporary feeling in the classic presentment of his themes. He was never archaic; so that the classic scenarium of his subjects, in his hands, appears as little antiquarian as a mediæval environment, shall we say, in the hands of Browning. Nausicaa, a full-length girlish figure, in green and white[Pg 38] draperies, standing in a doorway, and Serafina, another single figure, and A Study, were also shown the same year. At the Grosvenor Gallery were a Portrait of Miss Ruth Stewart Hodgson, a demure little damsel in outdoor attire, and a Study of a Girl's Head, full face.

NAUSICAA (1878)

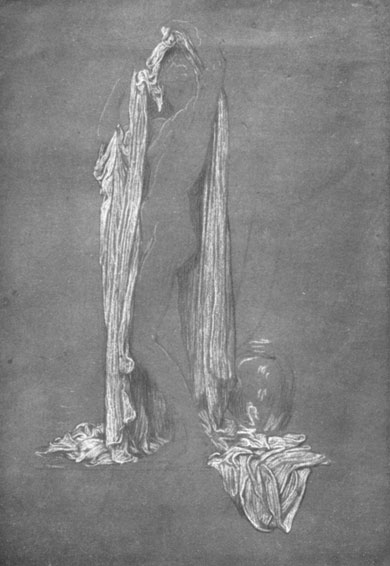

STUDY FOR "ELIJAH AND THE ANGEL"

CHAPTER VYear by Year—1878 to 1896On November 13th, 1878, Frederic Leighton was elected President of the Royal Academy, in succession to Sir Francis Grant, and immediately received the honour of knighthood. In 1879 Leighton sent eight contributions to the Academy, not one of which, with the possible exception of the Elijah, perhaps, has been counted among his masterpieces. Four of them belong to that group of ideal figure paintings which almost constitute a genre in themselves: Biondina, Catarina, Amarilla, and Neruccia, a girl with a red flower in her hair, in white dress, against a dark background. The finely austere Elijah in the Wilderness was an addition to the notable group of Scriptural paintings. In this picture the nude figure of the prophet is seen reclining on a rock, with head and arms thrown back, while beside him stands an angel holding bread and water. The striking and powerful Portrait of Professor Costa, the Portrait of the Countess Brownlow, and a portrait study, completed the list of the year's contributions, the largest number ever sent in by Leighton, before his election or afterward. This year ten of his landscape-studies in oil were exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery. It may be thought by the outsider that the coveted office of the President of the Royal Academy of Arts is,[Pg 40] in a way, an ornamental one,—some such golden sinecure as that of the old High Chamberlains. Nothing could be more mistaken. "Not everybody," wrote the late Mr. Underhill, who for some time, as private secretary to Sir Frederic Leighton, had special opportunities of knowing, "is aware of the tax upon a man's time and energy that is involved in the acceptance of the office in question. The post is a peculiar one, and requires a combination of talents not frequently to be found, inasmuch as it demands an established standing as a painter, together with great urbanity and considerable social position. The inroads which the occupancy of the office makes upon an artist's time are very considerable. There is, on the average, at least one Council meeting for every three weeks throughout the whole of the year. There are from time to time general assemblies for the election of new members and for other purposes, over which the President is bound, of course, to preside. For ten days or a fortnight in every April he has to be in attendance with the Council daily at Burlington House, for the purpose of selecting the pictures which are to be hung in the Spring Exhibition. He has to preside over the banquet which yearly precedes the opening of the Academy, and he has to act as host at the annual conversazione. Finally, it is his duty every other year to deliver a long, elaborate, and carefully prepared 'Discourse' upon matters connected with art, to the students who are for that purpose assembled. It is a post of much honour and small profit."

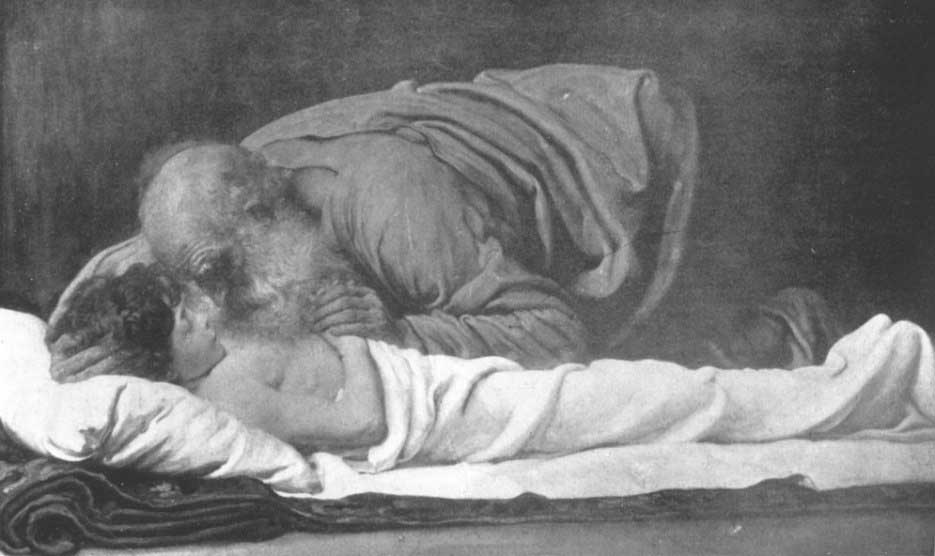

SISTER'S KISS (1880)

PORTRAIT OF SIGNOR COSTA (1879)

In filling this post, and neglecting no one of its smallest offices and endless small courtesies, an artist had needs be without the characteristic artist's defects of hesitation and delay; and in fact, Lord Leighton mastered, as much as any statesman of our time, the indispensable secret of despatch. We quote from Mr.[Pg 41] Underhill again: "To administer the affairs of the Academy, to fulfil a round of social semi-public and public engagements, and to paint pictures which invariably reach a high level of excellence, would of course be impossible—even to Sir Frederic Leighton—were it not for the fact that he makes the very most of the time at his disposal. 'That's the secret,' remarked a distinguished member of the Academy to the present writer some little time before the President's death; 'Sir Frederic knows exactly how long it will take to do a certain thing, and he apportions his time accordingly.' This being the case, no one will be surprised to learn that he attached the greatest importance to punctuality. He himself never failed to keep an appointment at the exact moment fixed upon, and he expected, of course, similar punctuality on the part of others. The stroke of eight from the Academy clock was the signal for Sir Frederic to enter the Council Room at Burlington House, and to open the deliberations of the body over which he presided. 'They will never again get a man to devote so much time and energy to the business of the Academy,' said Sir Frederic Leighton's most distinguished colleague shortly before his death; 'never again.'" And since that time the same tribute has been paid ungrudgingly in public and private often enough. In 1880, we are tempted by five canvases; of which the Sister's Kiss and Psamathe, are perhaps the most important. The former turns a garden wall to delightful account, in its picture of a child, who is seated upon it, and of her charmingly drawn elder sister, who gives the kiss. The composition of this picture may be seen in our reproduction, but the colour of the bronze green robe—of singular beauty—is of course not even suggested. More classic, perhaps, and not less picturesque,[Pg 42] is the Greek maiden, Psamathe, who was, if we remember aright, one of the Nereides. The artist has painted her sitting by the seashore, gazing over the Ægean, with her back turned to the spectator. Filmy garments, which have slipped from her shoulders on to the sand; arms folded about her knees; every detail of the picture carries out the effect of dreamy loveliness that pervades Psamathe and her surroundings. Iostephane is a three-quarter length figure, less than life size, of a girl in light yellow drapery, with violets in her fair hair, who stands facing the spectator and arranging her draperies over her right arm; there are marble columns and a fountain in the background. The Light of the Harem is a version of one of the groups in the fresco of The Industrial Arts of Peace at South Kensington. The picture now known as the Nymph of the Dargle was also exhibited this year under the title of Crenaia. It represents a small full-length figure facing the spectator; the river Dargle flows through Powerscourt, and forms the waterfall here represented in the background, hence its name. Rubinella, a girl with red gold hair was shown at the Summer Exhibition and a large number of sketches and studies at the Winter Exhibition of the Grosvenor Gallery this year. In 1881, the portrait of the Painter, painted by invitation in 1880 for the collection of autograph portraits of artists in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, deserves particular mention. Not even Mr. Watts' best portrait of Leighton is quite so like as this, which shows the striking head of the artist to great effect, assisted by the decorative President's robe and insignia. The Idyll, shown the same year, has been compared by some critics with the Cymon and Iphigenia, the scene and circumstance of both being to a certain degree similar, while there are[Pg 43] similar effects in both of colour and of composition. In the Idyll, we have a lovely female figure, lying at full length, attended by a second nymph, and by a piping man, all grouped beneath an arm of a beech tree, that extends overhead and shadows the upland ridge on which they have come to rest, while they gaze on a river winding among sunlit meads. The water reflects the blue and white of sky and clouds; the land is dashed by shadows. The nymphs' robes are red, blue, and pale yellow.

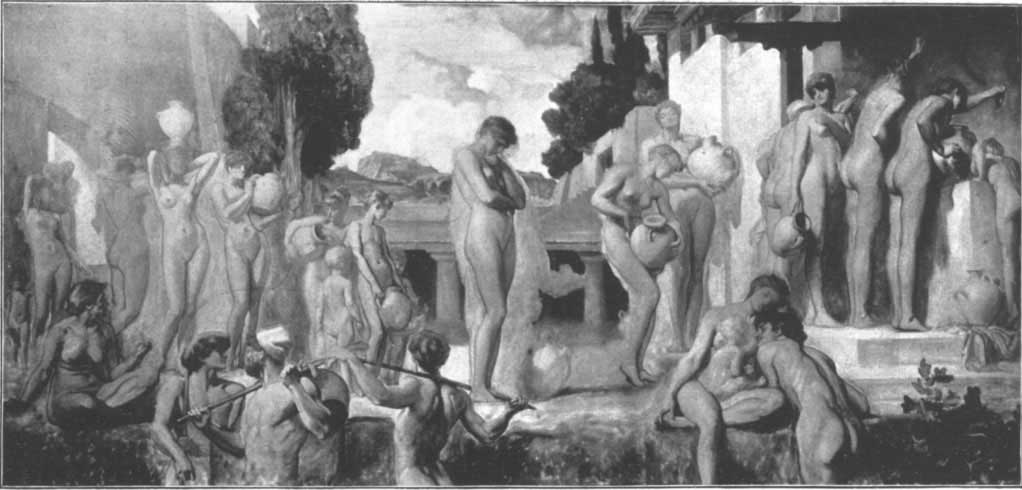

PHRYNE AT ELEUSIS (1882)

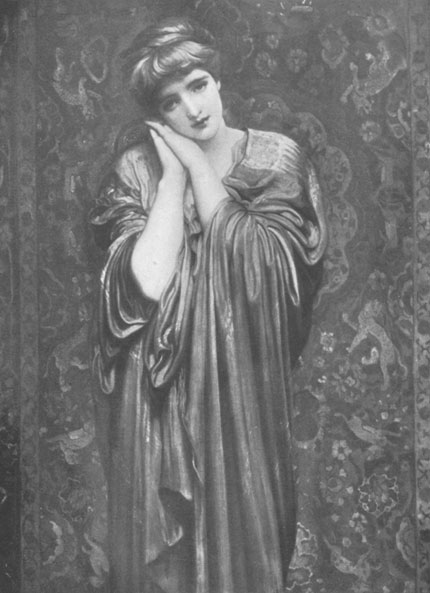

DAY DREAMS (1882)

We ought not to overlook another idyllic picture in the same exhibition, Whispers, an illustration of Horace's well-known line, "Lenesque sub noctem susurri." In this charming work, amid masses of crimson flowers and green leaves, two lovers are seen seated upon a marble bench, while he whispers tenderly in her ear, and she listens with dreamy eyes and maidenly mien. The noble picture of Elisha and the Shunamite's Son (reproduced at p. 114) was also shown this year, as well as Bianca, a fair-haired girl in a white dress, standing with folded arms, Viola, and two portraits, Mrs. Augustus Ralli, exhibited at the Royal Academy, and Mrs. Algernon Sartoris, at the Grosvenor Gallery. In the 1882 Academy appeared two of the most popular of Sir Frederic's pictures, Wedded and Day Dreams. In the latter, a fair Sybarite is pressing her cheek against her hands, as she stands near a tapestry, with eyes gazing far away, the images of love-dreams in them; her purple mantle, embroidered with silver, produces a charming effect of colour. Still more famous is Wedded,—"one of the happiest of Sir Frederic's designs," said a critic at the time, "and as a composition of lines, difficult, subtle, and original, may be called one of the most remarkable productions of this decade."[Pg 44] Other pictures shown this year were Antigone and the much-debated Phryne at Eleusis—a notable study of the famous hetaira, who is seen standing, and holding out with one hand the mass of her deep auburn hair. Her skin is of a ruddy golden hue, as if seen under a glow of sunlight. Red tissue, which falls from her shoulders and extended arms, and an olive-coloured mantle that has fallen at the foot of the marble columns behind her, backed by a sky, very characteristic of the painter, in which snowlike masses of cloud float in a southern azure, produce a total effect of a certain super-womanly order of beauty. A Design for a portion of a Proposed Decoration in St. Paul's, a picture entitled Melittion, and a Portrait of Mrs. Mocatta, were also hung at the Academy in 1882; Zeyra, a little Eastern child in plum coloured headdress, a rich bit of colour elaborately painted, was shown at the Grosvenor Gallery. In 1883, Memories, though not one of the most typical of Leighton's pictures, decidedly pleased the general public. It shows the half-length figure of a blonde, in a black and gold dress. More interesting artistically was a decorative frieze, The Dance, for a drawing-room, the design for which we reproduce, and which may, in so far, answer for itself. Other pictures of 1883 are Kittens, a full-length figure of a fair-haired child in purple and embroidered drapery, seated on a bench covered with a leopard skin, holding a rose in hand and looking down at a kitten sitting beside her; and the Vestal, a bust of a girl with her head and shoulders swathed with white gold-embroidered draperies. To this year also belongs a Portrait of Miss Nina Joachim, a child in a blue frock with crimson sash.

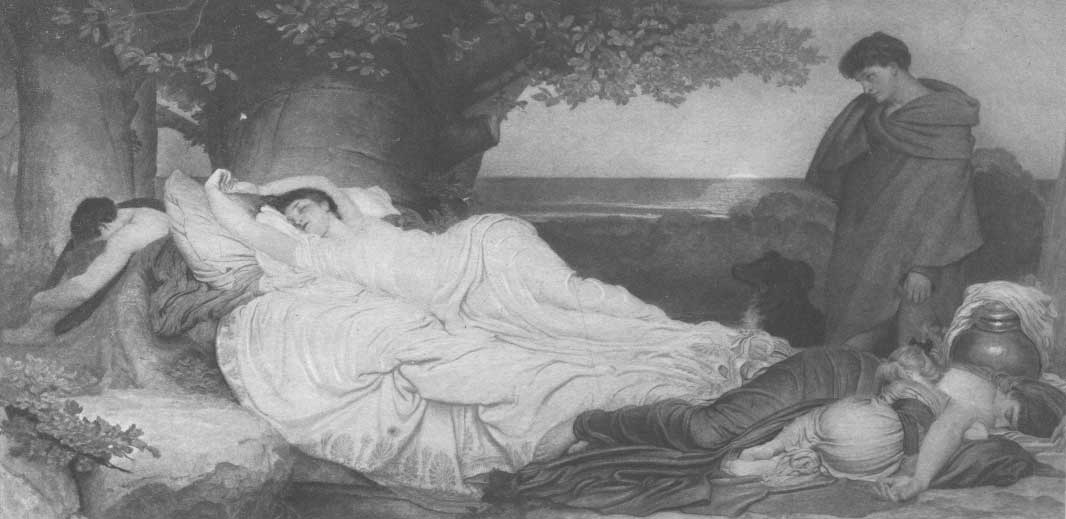

Cymon and Iphigenia.

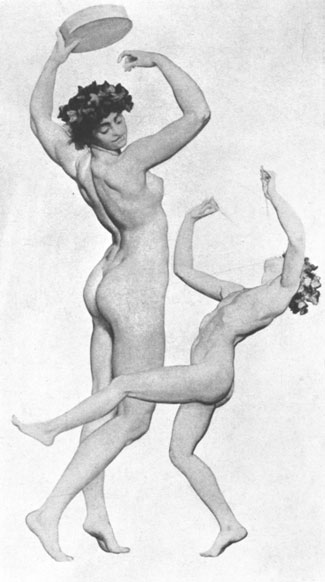

STUDIES FOR TWO FRIEZES "MUSIC" AND "THE DANCE"

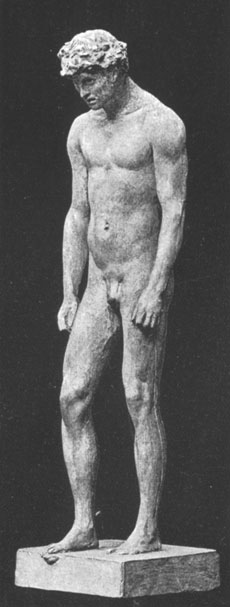

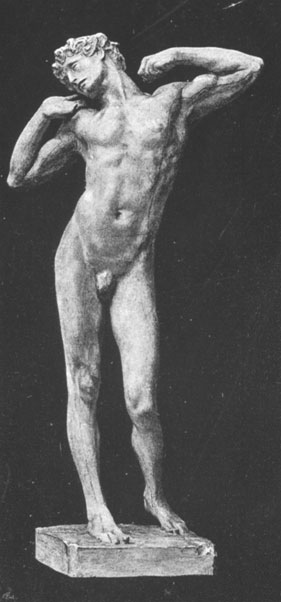

The next year, 1884, brought Letty, that most delightful of English maidens, A Nap, Sun Gleams, and[Pg 45] the imaginative and admirably romantic Cymon and Iphigenia. Letty was one of Leighton's pictures which particularly excited Mr. Ruskin's admiration. It shows a simply pretty child, with soft brown hair under a black hat, a saffron kerchief about her neck. The Letty and the Cymon and Iphigenia, with a few other notable pictures, did much to leave a pleasant recollection of the exceptional Academy of 1884. "A more original effect of light and colour, used in the broad, true, and ideal treatment of lovely forms," said a French critic, "we do not remember to have seen at the Academy, than that produced by the Cymon and Iphigenia." Engravings and other reproductions of the picture have made its design, at any rate, almost as familiar now as Boccaccio's tale itself. There are some divergences, however, in the two versions. Boccaccio's tale is a tale of spring; Sir Frederic, the better to carry out his conception of the drowsy desuetude of sleep, and of that sense of pleasant but absolute weariness which one associates with the season of hot days and short nights, has changed the spring into that riper summer-time which is on the verge of autumn; and that hour of late sunset which is on the verge of night. Under its rich glow lies the sleeping Iphigenia, draped in folds upon folds of white, and her attendants; while Cymon, who is as unlike the boor of tradition as Spenser's Colin Clout is unlike an ordinary Cumbrian herdsman, stands hard-by, wondering, pensively wrapt in so exquisite a vision. Altogether, a great presentment of an immortal idyll; so treated, indeed, that it becomes much more than a mere reading of Boccaccio, and gives an ideal picture of Sleep itself,—that Sleep which so many artists and poets have tried at one time or another to render. In 1885, among the five contributions of the President[Pg 46] to the Academy, appeared the vivacious portrait of Lord Rosebery's little daughter, The Lady Sybil Primrose, who appears in white with a blue sash, carrying a doll. A Portrait of Mrs. A. Hichens and Phœbe were the only other pictures this year. A frieze, Music, was shown, and at the Grosvenor Gallery A Study of a fair-haired girl, in green velvet dress. 1886 was chiefly notable for the statue in bronze of The Sluggard, in which Leighton again furnished us with a plastic characterization of Sleep, which he designed by way of contrast to his statue of the struggling Athlete. It was suggested, Mr. Spielmann says, by accidental circumstances. The model who had been sitting to him fell a-yawning in his interval of rest, and charmed the artist, not only with his exceptional beauty of line and play of muscle, but also with the artistic contrast of energy and languor. But that he might not lay himself open to the charge that the work was a glorification of indolence, the sculptor made concession to what after all was an artistic suggestion, and placed under the yawner's foot

"The glorious wreath of laurel leaves

Heel trodden and despised." The graceful statuette of a little girl who is alarmed by a toad on the edge of a pool or stream of water, called Needless Alarms, appeared at the same time; and was so much admired by the President's colleague, Sir John Everett Millais, that he wished to purchase it, whereupon Sir Frederic presented it to him, and received, in return, the charming picture of Shelling Peas, which Sir John painted specially for this pleasant exchange. In 1886 also appeared the Decoration in Painting for a Music Room, destined for New York, which is illustrated[7] [Pg 47] by the completed work, and its preliminary studies from life for it. Gulnihal, a single figure, is the only other painting exhibited at the Academy in this year.

THE LAST WATCH OF HERO (1887)

PORTRAIT OF THE LADY SYBIL PRIMROSE (1885)

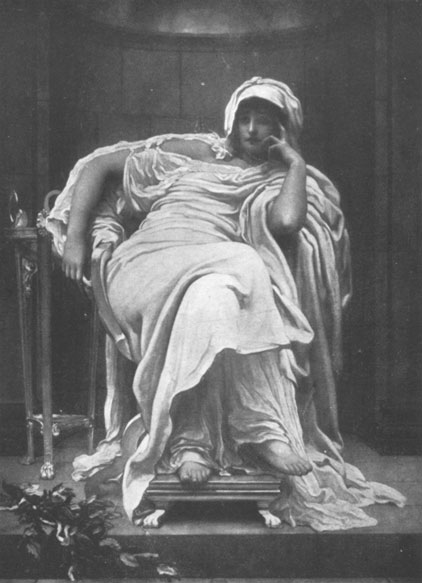

In 1887 appeared a picture which seems scarcely to have received its due appreciation, The Jealousy of Simætha the Sorceress. This is a seated figure in yellow and white drapery, with a purple mantle wrapped around her shoulders; a well-wrought, finely-rendered work. The Last Watch of Hero, also first seen this year, is now in the Manchester Corporation Gallery. It is in two compartments; in the upper, and larger, Hero, clad in pink drapery, is seen drawing aside a curtain and gazing out over the sea. Below, in the smaller panel, is the body of the dead Leander, on a rock washed by the waves. A quotation from Sir Edwin Arnold's translation of Musæus was appended to its title:

"With aching heart she scanned the sea-face dim.

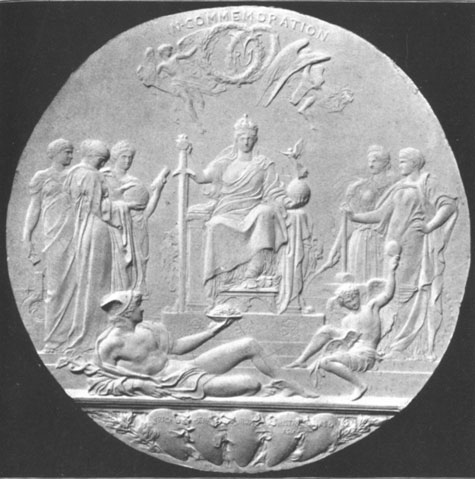

**** Lo! at the turret's foot his body lay, Rolled on the stones and washed with breaking spray." A picture of a little girl with yellow hair and pale blue eyes, entitled with a verse by Robert Browning:

"Yellow and pale as ripened corn

Which Autumn's kiss frees,—grain from sheath,— Such was her hair, while her eyes beneath Showed Spring's faint violets freshly born," was in the same exhibition, and also a design for the reverse of the Jubilee medallion, executed for her Majesty's Government. In 1888 appeared another large work, which, although not absolutely a procession, has much in common with the Cimabue, the Syracusan Bride, and The Daphnephoria.[Pg 48] It was entitled Captive Andromache, and accompanied by a fragment of the "Iliad," translated by E. B. Browning:

... "Some standing by

Marking thy tears fall, shall say, 'This is she, The wife of that same Hector that fought best Of all the Trojans when all fought for Troy.'" This, and a Portrait of Amy, Lady Coleridge, were the artist's only contributions to the Royal Academy of 1888. The Portraits of the Misses Stewart Hodgson is also of this year, which saw four landscape studies exhibited at the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours, and five at the Royal Society of British Artists, Suffolk Street. The Sibyl, exhibited in 1889, is a full-length figure swathed in lilac drapery, seated with her legs crossed, on a chair, her chin supported by her left hand, and gazing out of the picture. Beside her are scrolls, and a sombre sky is behind the figure. Invocation, a girl in white robes with arms raised above her head, and a Portrait of Mrs. F. Lucas, were also shown; but Greek Girls playing at Ball is not only the most important, but is also a picture that shows the mannerism of Lord Leighton's treatment of drapery at its finest. Elsewhere the undulating snaky coils may be somewhat distressing, here they float in the air and help the suggestion of movement. The landscape at the back is also both typical and beautiful. An Elegy was the fifth of the artist's contributions to the Academy of 1889. In 1890 The Bath of Psyche appeared at the Academy. This at once established its position as a popular favourite, and has probably been more widely reproduced than any other. It was purchased under the terms of the Chantrey Bequest, and is now in the Tate Gallery. It was suggested, so Mr. M. H. Spielmann tells us, by the[Pg 49] "paper-knife" picture, as Lord Leighton called it, which he had painted for Sir L. Alma-Tadema's wall screen. Solitude was also shown this year, and the Tragic Poetess, a full-length figure, clad in blue and purple drapery, on a terrace, with the sea beyond. The fourth picture at the Academy was a very faithfully painted transcript of The Arab Hall, at No. 2, Holland Park Road.

GREEK GIRLS PLAYING AT BALL (1889)

THE BATH OF PSYCHE (1890)