|

|

Augusta Stylianou Gallery

Artist Index  BRITISH

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AGENTS | |

|---|---|

| AMERICA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK |

| AUSTRALASIA | OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 205 Flinders Lane, MELBOURNE |

| CANADA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD. St. Martin's House, 70 Bond Street, TORONTO |

| INDIA | MACMILLAN & COMPANY, LTD. Macmillan Building, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA |

| OWNER OF ORIGINAL | |

| 1. Confidences | Mrs. Carl Meyer |

| 2. Idleness | Sir Edward Tennant, Bart. |

| 3. Diligence | " |

| 4. Belinda, Billet-Doux | T. J. Barratt, Esq. |

| 5. The Effects of Youthful Extravagance and Idleness | Sir Walter Gilbey, Bart. |

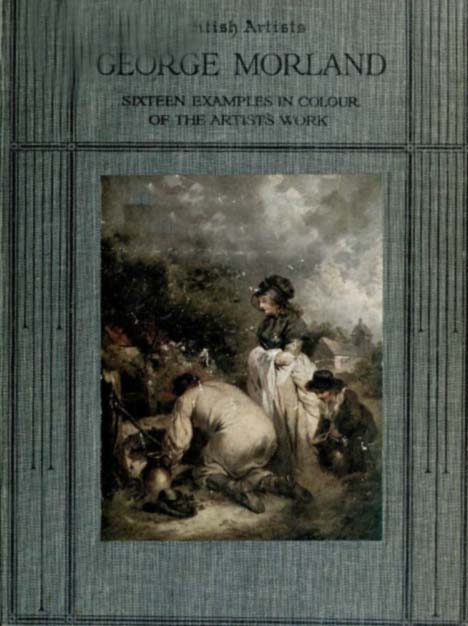

| *6. The Dipping-Well | " |

| 7. The Deserter's Farewell | " |

| 8. The Deserter Pardoned | Barnet Lewis, Esq. |

| 9. The Fox Inn | Sir Walter Gilbey, Bart. |

| 10. Gathering Sticks | " |

| 11. Morning; or, The Benevolent Sportsman | J. Beecham, Esq. |

| 12. Farmyard | T. J. Barratt, Esq. |

| 13. Gipsies in a Wood | Sir Walter Gilbey, Bart. |

| 14. Evening; or, The Post-Boy's Return | Lord Swaythling |

| 15. Winter: Skating | Sir Walter Gilbey, Bart. |

| 16. Justice; or, The Merciless Bailiff | " |

* On the cover

(Born June 26, 1763; died October 29, 1804)

The son of Henry Robert, who combined with the exercise of the painter's art the work of cleaning and restoring old pictures, it may fairly be said of George Morland that he was reared in the studio. His genius betrayed itself at a very early age, some chalk drawings tinged with crayon which he produced when ten years old being exhibited in the Royal Academy. Such education as he received was given him at home; but it would seem that his father kept him too closely at work with pencil and brush to leave the boy opportunity of gleaning knowledge from books.

When fourteen years old, his father bound him apprentice to himself, having ere then fully recognized the artistic genius which promised him material advantages. Others than his father recognized George Morland's genius: Sir Joshua Reynolds, who gave the boy the run of his studio, urged that he be brought up in "the grand line" of art; and when his indentures expired, Romney offered to take him as pupil at a salary of £300 a year. Sir Joshua's recommendation was declined by the father; to Romney's offer George would have nothing to say.

George was slow to discover a spirit of independence, even when he came of age, remaining at home for at least six months after he had reached man's estate. His independent career began in 1785, when he was twenty-two years old. Having escaped from the hands of an Irish picture-dealer who worked him for his own advantage, he spent a few months at Margate, devoting himself with success to the painting of portraits he had been invited to do by a Mrs. Hill. He seems to have been tolerably industrious, for he was able to live in comfort and to share the amusements offered by a then fashionable watering-place. On his own showing he began to acquire at this period a taste for drink; but he was young, of robust constitution and fond of exercise, and his indulgence was not excessive.

After his return to London in 1786, he lived sometimes with his parents, and sometimes elsewhere. Among his acquaintances he numbered William Ward, the famous engraver, who had, ere this time, reproduced at least one of Morland's pictures. He became a frequent visitor at Ward's house at Kensal Green, and before long took up his quarters with the family, consisting of the engraver, his mother, and two sisters. Anne Ward, a very beautiful girl, soon captivated Morland, and they were married at St. Paul's, Hammersmith, on September 22, 1786.

He appears to have been steady and industrious during his residence at Kensal Green, and he continued to work hard for the first few months after his marriage, which was followed a month later by the wedding of William Ward to Maria Morland.

A joint establishment set up by the two young couples in High Street, Marylebone, endured for about three months; a quarrel ended in separation, and the Morlands found new quarters in Great Portland Street. It was during his early married life that the artist painted, among others, the six famous pictures known as the "Lætitia Series," for which his wife sat as model. The move to Great Portland Street was the first of the numerous changes of residence made by Morland during his married life. During the first two years these changes were dictated by the success which enabled him to house himself more comfortably; but the period of steadiness and hard work was so brief that it may be dismissed in a few lines. The advent of a still-born child, and the knowledge that he might not hope to be a father, appear to have been the means of unsettling him in his domestic capacity; and the indifference of his wife to the music he loved may have contributed to the same end; but the fact remains that within a year of marriage Morland began to neglect her. He acquired the habit of making trips into the country during the day and resorting to musical gatherings at night, leaving Mrs. Morland much to her own devices.

He was not idle in the ordinary sense of the word. Gifted with extraordinary facility, he painted numerous pictures which, if sold in business-like fashion, would have produced enough to raise him to affluence; but he had inherited from his father, in intensified form, a singular lack of common sense. He sold his pictures for any sum that might be offered, regardless of the fact that the purchasers took them direct to dealers in the certainty of disposing of them for double the money. Even while working on these lines his prolific brush and steadily increasing reputation enabled him to make a good income; but success, if the expression may be used, "went to his head." He launched out into the wildest extravagance, regulating his expenditure by the ease with which he could borrow rather than by the ease with which he could earn, and while he had cash in his pocket he would not work. As his reputation grew, largely through the medium of the engravings made from his pictures, the anxiety of dealers and others to secure works from his easel grew in ratio with it; his natural readiness to borrow was encouraged on every side by those who intended, or hoped, to obtain in pictures more than the equivalent of the money they advanced, and Morland gave promissory notes with joyful recklessness, absolutely indifferent to the load of debt he was rolling up.

The inevitable crash came in 1789, when for the first time he found it expedient to fly from his creditors. There is evidence in the shape of pictures to show that he sought refuge in the Isle of Wight; but he did not long remain there. His legal adviser, Mr. Wedd, took his affairs in hand, and he returned to London to go into temporary hiding while matters were adjusted by means of a "Letter of Licence," a document which secured him from arrest by making terms with his creditors. Under this bond he pledged himself to pay off his liabilities at the rate of £120 a month. How his credit declined in subsequent years is proved by the series of "Letters of Licence" procured for him. These respectively pledged him to pay £100, £50, and the last only £10, per month.

Perhaps the most pathetic feature of Morland's career is the circumstance that the period which saw his greatest exertions to escape from creditors coincided with that during which he produced his finest work. "Inside of a Stable" (now in the National Gallery, and known as "The Farmer's Stable") attracted universal attention when exhibited at the Royal Academy of 1791, and raised the painter's fame to its zenith. Commissions for pictures, with advances of money, were pressed upon him on all sides; Morland accepted the cash, promised the pictures, and launched out into wilder extravagance. He kept eight horses, or more, for the country excursions on which his friends joined him; he entertained lavishly; he drew round him a disreputable crew of prize-fighters and similar characters, who lived upon him; and he scattered money with a reckless hand. He could always find those who were eager to lend, and, revelling in the ease with which he could raise money, would not paint until he felt the pinch of need. When out of funds he would work, and did so with the amazing speed and deftness that stamp him a genius. There is no doubt that he drank at this time, but his love of riding and outdoor life enabled him to throw off the effects of over-indulgence.

His career from 1791 to 1799 was one long series of flights from one place to another to avoid the creditors who pressed for money. From time to time Mr. Wedd arranged his affairs in such wise that he could show his face in London; and at other times men who wanted pictures relieved him from his difficulties to the same end; but viewing these nine years as a whole, the general impression left on the mind is one of a hunted animal—now in hiding in the Isle of Wight, now in Leicestershire, now in mean lodgings in a poor part of London, now out of sight. It is only occasionally that we can trace his place of abode. He would go into hiding, with friend or servant sworn to secrecy, and while in hiding would work, and his companion would bring his paintings up to London and dispose of them.

In 1798 he spent six months at Hackney, comparatively free from the attentions of creditors, and during this brief period he executed some pictures which compare favourably with those painted in his best years (1790-1793).

The improvement was not maintained. Morland, whose nerves were now suffering from the periodical debauches in which he indulged, and also, no doubt, from the ceaseless pressure of creditors, left Hackney and found refuge first in London and then in the Isle of Wight; and from the Island he came, in December, 1799, to seek escape by procuring his own arrest at the hands of friends. Nominally a prisoner in King's Bench, he was "granted the rules," and took a house in St. George's Fields, where he lived for a couple of years with his wife and his brother Henry. When granted his release under 41 Geo. III., he remained in St. George's Fields for a few months, and then, for the sake of change, went to Highgate. From this time, during the few remaining years of his life, Morland was an irreclaimable drunkard. His constitution was undermined, he could no longer take horse exercise, and his excesses told upon him rapidly. To the fact that he was now unable to work until he had taken stimulant is due the common report that he "painted best when drunk." Nevertheless, his reputation remained, and he was overwhelmed by attentions from those who wanted pictures. The great aim of these patrons now was to induce him to live with them that they might exercise some control over his propensity for liquor, and keep him at work. His brother Henry was most successful in this regard; for some considerable time George lived with him, and, during his frequently broken stay, painted a very large number of pictures, Henry paying him a specified sum per day. This has been stated as £2 2s. and £4 4s., but in either case Henry's profits must have been great.

Collins, one of Morland's biographers, has given us a melancholy word-picture of the artist in these, his later days—besodden with drink, his face showing every sign of excess; nerves gone, sight failing, one hand palsied; yet able to produce works for which everyone clamoured.

Leaving his brother's house, he went from one friend to another. For many months he occupied lodgings in a sponging-house in Rolls Buildings, kept by a sheriff's officer named Donatty; here he was free to come and go as he pleased, yet was secure from arrest, and Donatty became the owner of a number of fine pictures.

It was soon after he left Rolls Buildings to reside with some other friend that he was arrested for the last time. The sum due was trifling, but Morland had no means of discharging it, and was conveyed to a sponging-house in Eyre Place, Eyre Street Hill, Hatton Garden. Refusing the offers of friends to pay the debt, he insisted on remaining in custody. He had frequently shown bitter resentment at the way his quondam friends worked him for their own advantage, and preferred to stay where he was. He strove to work; but the overtaxed brain and body refused, and while at his easel he fell from his chair in a fit. For eight days he lay almost insensible with brain fever, and then, without recovering consciousness, he died.

George Morland's was a singular character. His love of flattery and dread of affront may account for his choice of companions; he shrank from association with his social superiors, finding congenial friends among pugilists, grooms, sweeps, and persons whom he suffered to profit by his recklessness in money matters. Endowed with a keen sense of humour, whose artistic expression found vent in caricature, he found his principal amusement in playing schoolboy practical jokes. George Dawe hits off his character in a sentence when he says that Morland "never became a man"; throughout his life his faults were the faults of a boy and his virtues the virtues of a boy.

He and his wife were unhappy together and miserable apart. When he had a home she shared it, and if he had not, he sent her money—when he could. That he inspired her to the utmost with the affection he was able to engage from all who came in contact with him, is proved by the fact that news of his death killed her.

Morland's art embraced great variety of subjects. His earlier popular successes were achieved by his figure paintings, and of these it is worth noticing that among the best were pictures which pointed morals he studiously ignored in his own career. The great popularity of W. R. Bigg's pictures of child-life led the dealers to persuade Morland to take up the same line of work, and in his pictures of child-life the artist shows himself what we know him to have been—a lover of children and one who had perfect understanding of them. The insight with which he portrayed children is only equalled by that which distinguishes his animal paintings. Morland's horses, ponies, asses, calves, and pigs, are entirely his own; they possess a character which stamps them as the work of one who had almost uncanny knowledge. He rarely painted a well-bred horse; the animal that appealed to him was the farmer's work-horse or the slave of the carter, and on these he expended his greatest skill. Only an artist who was also a horseman could paint the horse as he painted it. He has been described as a "pig painter," but this refers rather to the success with which he proved the artistic possibilities of subjects so unpromising than to the number of works in which pigs occur, though it is admitted that he was fond of painting such pictures. His asses and calves, in their kind, are equal to his horses; cows he seldom painted, and when he essayed to do sheep he was not conspicuously successful.

The composition of his works is rarely otherwise than pleasing, a point the more worthy of notice when we remember that he never made studies, but developed the picture under his hand as he worked upon it. The straightforward simplicity, the absence of subtlety of his art, may perhaps be in some measure an outcome of his method. His schemes of colouring were subdued rather than brilliant; one of his few principles of painting was that a touch of pure red should appear in every picture, and we very generally find it.

Once Morland left his father's roof, his artistic education in one sense ceased. He took not the slightest interest in the works of other painters of whatever period; on the contrary, he avoided study of art lest he should become an imitator; and went direct to Nature for all he required. To this practice we may attribute his originality.

Since I had the pleasure of collaborating with Sir Walter Gilbey in writing the biography of the painter, it has been pointed out that the artist with whom George Morland has more in common than any is Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699-1779). The resemblance between the figure subjects in which each excelled is certainly striking; and this resemblance, regarded in conjunction with the French nationality of Morland's mother, has evoked the suggestion that the English painter may have derived hereditary talent from the maternal side. Search through the registers of the churches of the parish in which Henry Robert Morland lived fails to reveal entry relating to his marriage. It may be recalled, however, that Chardin's two daughters died in infancy.

E. D. CUMING.

==--==--==

==++==++==