Augusta Stylianou Gallery

<-----===========------->

Loading

|

Michelangelo

David

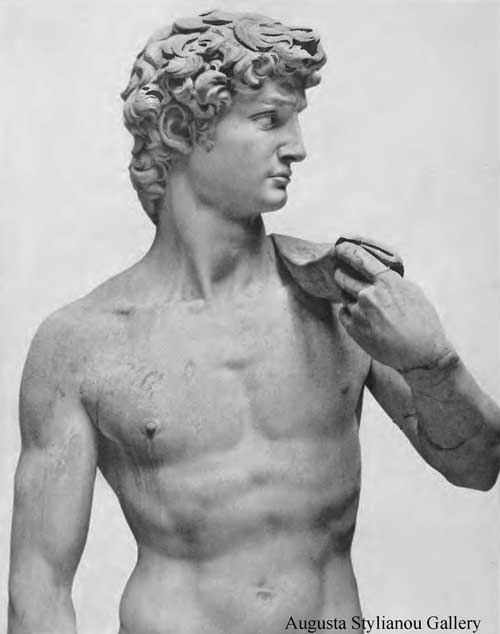

"David" is a masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture created between 1501 and 1504, by the Italian artist Michelangelo. It is a 5.17 metre (17 feet)[1] marble statue of a standing male nude. The statue represents the Biblical hero David, a favoured subject in the art of Florence.

Originally commissioned as one of a series to be positioned high up on the facade of Florence Cathedral, the statue was instead placed in a public square, outside the Palazzo della Signoria, the seat of civic government in Florence, where it was unveiled on 8 September 1504. Because of the nature of the hero that it represented, it soon came to symbolise the defence of civil liberties embodied in the Florentine Republic, an independent city-state threatened on all sides by more powerful rival states and by the hegemony of the Medici family. The eyes of David, with a warning glare, were turned towards Rome.[2] The statue was moved to the Accademia Gallery in Florence in 1873, and later replaced at the original location by a replica.

History

The history of the statue of David precedes Michelangelo's work on it from 1501 to 1504.[3] Prior to Michelangelo's involvement, the Overseers of the people of Office of Works of the Duomo (Operai), consisting mostly of members of the influential woolen cloth guild, the Arte della Lana, had plans to commission a series of twelve large Old Testament sculptures for the buttresses of the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Until then, only two had been created independently by Donatello and his assistant, Agostino di Duccio. Eager to continue their project, in 1464, they again contracted Agostino to create a sculpture of David. A block of marble was provided, from a quarry in Carrara, a town in the Apuan Alps in northern Tuscany. Agostino only got as far as beginning to shape the legs, feet and the figure, roughing out some drapery and probably gouging a hole between the legs. His association with the project ceased, for reasons unknown, with the death of his master Donatello in 1466, and Antonio Rossellino was commissioned to take up where Agostino had left off.

Rossellino's contract was terminated, soon thereafter, and the block of marble remained neglected for twenty-five years, all the while exposed to the elements in the yard of the cathedral workshop. This was of great concern to the Operai authorities, as such a large piece of marble was both costly, and represented a large amount of labour and difficulty in its transportation to Florence. In 1500, an inventory of the cathedral workshops described the piece as "a certain figure of marble called David, badly blocked out and supine." A year later, documents showed that the Operai were determined to find an artist who could take this large piece of marble and turn it into a finished work of art. They ordered the block of stone, which they called The Giant, "raised on its feet" so that a master experienced in this kind of work might examine it and express an opinion. Though Leonardo da Vinci and others were consulted, it was young Michelangelo, only twenty-six years old, who convinced the Operai that he deserved the commission. On August 16, 1501, Michelangelo was given the official contract to undertake this challenging new task. He began carving the statue early in the morning on Monday, September 13, a month after he was awarded the contract. He would work on the massive biblical hero for 3 years.

On January 25, 1504, when the sculpture was nearing completion, a committee of Florentine artists including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli met to decide on an appropriate site for David. The majority, led by Giuliano da Sangallo and supported by Leonardo and Piero di Cosimo, among others, believed that due to the imperfections in the marble the sculpture should be placed under the roof of the Loggia dei Lanzi on Piazza della Signoria. Only a rather minor view, supported by Botticelli, believed that the sculpture should be situated on or near the cathedral. Eventually David was placed in front of the entrance to the Palazzo Vecchio, also on Piazza della Signoria, replacing Donatello's bronze sculpture of Judith and Holofernes, which embodied a comparable theme of heroic resistance. It took four days to move the statue from Michelangelo's workshop onto the Piazza della Signoria.

In 2010, a dispute over the ownership of David arose when, based on a legal review of historical documents, the Italian federal Culture Ministry claimed ownership of the statue in opposition to the city of Florence, where it has always been located. Florence disputes the state claim.[4][5]

Interpretation

Michelangelo's David differs from previous representations of the subject in that David is not depicted with the head of the slain Goliath, as he is in Donatello's and Verrocchio's statues of David. According to Helen Gardner David is depicted before his battle with Goliath.[6] Instead of being shown victorious over a foe much larger than he, David looks tense and ready for combat. His veins bulge out of his lowered right hand and the twist of his body effectively conveys to the viewer the feeling that he is in motion, an impression heightened with contrapposto. The statue perhaps shows David after he has made the decision to fight Goliath but before the battle has actually taken place. It is a representation of the moment between conscious choice and conscious action.[citation needed] However, other experts (including Giuseppe Andreani, the current director of Accademia Gallery) consider the depiction to represent the moment immediately after battle, as David serenely contemplates his victory.[citation neede

A copy of the statue standing in the original location of David, in front of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

Michelangelo's David is a Renaissance interpretation of a common ancient Greek theme of the standing heroic male nude. In the High Renaissance, contrapposto poses were thought of as a distinctive feature of antique sculpture. In David, the figure stands with one leg holding its full weight and the other leg relaxed. This classic pose causes the figure’s hips and shoulders to rest at opposite angles, giving a slight s-curve to the entire torso. In addition, the statue faces to the left while the left arm leans on his left shoulder with his sling flung down behind his back.[citation needed] Michelangelo’s David has become one of the most recognized pieces of Renaissance Sculpture, becoming a symbol of both strength and youthful human beauty.

The proportions of the David are atypical of Michelangelo's work; the figure being only seven and a half heads tall as opposed to more heroic proportions commonly used by Michelangelo. The hands and feet are also sculpted particularly large. These items may be due to the fact that the David was originally intended to be placed on a church façade or high pedestal, where the important parts of the sculpture would necessarily be accentuated in order to be visible from below. Another theory is that in the story, David was only thirteen or fourteen years old when he encountered Goliath, therefore the over large hands and feet would be intended to portray an adolescent male not fully grown. Others suggest the head and hands were created larger to represent thinking with the brain and working with the hands, while the genitals were created smaller to imply that David was not allowing himself to make decisions with pleasure in mind. It is said that his right hand is larger than his left hand because he had the "right hand" of God while defeating Goliath. It is also said that it is bigger because of balance issues so the statue would not fall over.

Commentators have noted David's apparently uncircumcised penis, which is at odds with Judaic practice, but is considered consistent with the conventions of Renaissance art.[7]

Conservation

In 1873 the statue of David was removed from the piazza, to protect it from damage, and displayed in the Accademia Gallery, Florence, where it attracts many visitors. A replica was placed in the Piazza della Signoria in 1910.

In 1991, a deranged man attacked the statue with a hammer he had concealed beneath his jacket,[8] in the process damaging the toes of the left foot before being restrained. The samples obtained from that incident allowed scientists to determine that the marble used was obtained from the Fantiscritti quarries in Miseglia, the central of three small valleys in Carrara. The marble in question contains many microscopic holes that cause it to deteriorate faster than other marbles. Because of the marble's degradation, from 2003 to 2004 the statue was given its first major cleaning since 1843. Some experts opposed the use of water to clean the statue, fearing further deterioration. Under the direction of Dr. Franca Falleti, senior restorers Monica Eichmann and Cinzia Pamigoni undertook the job of restoring the statue.[9]

In 2008, plans were proposed to insulate the statue from the vibration of tourists' footsteps at Florence's Galleria dell'Accademia, to prevent damage to the marble.[10]

Replicas

Main article: Replicas of Michelangelo's David

The statue has been reproduced many times. The plaster cast of David at the Victoria and Albert Museum has a detachable plaster fig leaf which is displayed nearby. It was created for visits by Queen Victoria and other important ladies, when it was hung on the figure using two strategically placed hooks.[11]

By the 20th century, Michelangelo's David had become iconic shorthand for "culture".[12] David has been endlessly reproduced,[13] in plaster and imitation marble fibreglass, attempting to lend an atmosphere of culture even in some unlikely settings, such as beach resorts, gambling casinos and model railroads.[14]

References

Bibliography

* Hall, James, Michelangelo and the Reinvention of the Human Body 2005.

* Hartt, Frederick, Michelangelo: the complete sculpture

* Hibbard, Howard. Michelangelo

* Hirst Michael, “Michelangelo In Florence: David In 1503 And Hercules In 1506”

* Pope-Hennessy, John (1996). Italian High Renaissance and Baroque Sculpture. London: Phaidon

* Kleiner, Fred S.; Christin J. Mamiya (2001). Gardner's Art Through the Ages. Fort Worth: Harcourt College.

* Seymour, Charles, Jr. Michelangelo's David : a search for identity (Mellon Studies in the Humanities) 1967.

* Stokstad, Marilyn (1999), Art History. 2nd Ed. Vol. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

* Vasari, Giorgio, Lives of the Artists (Penguin Books), “Life of Michelangelo” pp. 325–442. Vasari's report on the origin and placement of David has been undermined by modern historians.

Notes

1. ^ The height of the David was recorded incorrectly and the mistake proliferated through many art history publications. See [1] and [2]

2. ^ J. Huston McCulloch, David: A New Perspective, (2007) accessed 13-02-2010

3. ^ The genesis of David was discussed in Seymour 1967.

4. ^ Povoledo, Elisabetta (August 31, 2010). "Who Owns Michelangelo’s ‘David’?". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/world/europe/01david.html. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

5. ^ Pisa, Nick (August 16, 2010). "Florence vs Italy: Michelangelo's David at centre of ownership row". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/italy/7946627/Florence-vs-Italy-Michelangelos-David-at-centre-of-ownership-row.html. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

6. ^ Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, Christin J. MamiyaIt, Gardner's Art Through the Ages retrieved February 17, 2009

7. ^ "Michelangelo and Medicine" [3] Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

8. ^ "a man the police described as deranged broke part of a toe with a hammer, saying a 16th century Venetian painter's model ordered him to do so." Cowell, Alan. "Michelangelo's David Is Damaged". New York Times, 1991-09-15. Retrieved on 2008-05-23.

9. ^ Eric Scigliano. "Inglorious Restorations. Destroying Old Masterpieces in Order to Save Them." Harper's Magazine. August 2005, 61–68.

10. ^ Michelangelo's David 'may crack'. BBC News, 2008-09-19. Retrieved on 2008-09-19.

11. ^ "David's Fig Leaf". Victoria and Albert Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/sculpture/stories/david/index.html. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

12. ^ A. Synnott, Pink Flamingoes: Symbols and Symbolism in Yard Art, 1990.

13. ^ " You need not travel to Florence to see Michelangelo's David. You can see it well enough for educational purposes in reproduction," asserted E.B. Feldman in 1973 (Feldman, "The teacher as model critic", Journal of Aesthetic Education, 1973).

14. ^ That "typical examples of kitsch include fridge magnets showing Michelangelo’s David." is reported even in the British Medical Journal (J Launer, "Medical kitsch", BMJ 2000)

From Wikipedia. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License

Michelangelo